[Translation by Human Rights in China]

On our list of victims there is a Dai Jinping (戴金平), whose surviving family lives in Xiantao City, Hubei Province.

Before we left Beijing, we learned from the brief introduction of Dai Jinping’s family in the registry of survivors and families of victims that he was his family’s eldest son. Already overwhelmed with grief by his death, Dai’s mother Zhu Jingrong (朱镜蓉) had to face even more tragedies that befell her family one after another: less than six months after Dai’s death, his younger brother became schizophrenic, and his father Dai Congde (戴丛德) was beaten to death at work by a thug. Zhu Jingrong struggled with poor health and dire poverty. We’ve always treated hers as a household facing extreme hardship.

Every year, we delivered our humanitarian assistance to her through her nephew-in-law, who lives in the city of Xiantao. Her nephew-in-law had called me a few months ago to tell me his new cell phone number. I left it on my cell phone and forgot about it. As a result, we had some difficulty in locating Zhu Jingrong.

Although we had her home address, we had no idea where her house was located or how difficult transportation was. We didn’t know how much the rural folks knew about June Fourth. If we just arrive out of the blue, the locals would immediately know from our accent that we were from out of town. Zhu Jingrong is a village peasant woman to the core and has little contact with the outside world. Before meeting her, we had been concerned that two strangers like us carrying a still camera and video camera visiting an 80-year-old woman would draw the attention of local officials. After much thought and discussion with Guo Liying, we decided that we would first try to look for her without our equipment and we would go back to her the following day for the interview.

Her house is located in the Miancheng Ethnic Hui Township in Xiantao City.

The village where her house is located is not far from the highway. From the highway we could see the outline of the village. A 30-minute walk along a small road took us to the village entrance. We asked the villagers for directions and they enthusiastically assisted us. Pointing at a man in his 40s standing by the side of the road, they told us that he was Zhu Jingrong’s son and that we should just follow him.

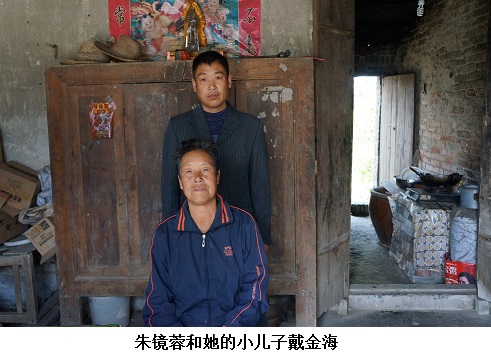

I believe this must be her son who suffers from schizophrenia. His name is Dai Jinhai (戴金海). He looked quite normal now. He led us to the door of his house. A woman who looked less than 70 years old walked toward us. As we were still not sure, she came before us, told us that she was Zhu Jingrong, and asked what she could help us with. We were surprised that she was so young. She is 70 years old. Among all the mothers we know of who lost their children, she is the youngest.

We told her that we came from Beijing and were there on behalf of victims’ families to visit them. Although surprised, she happily invited us in.

I was quite excited to have found her. It was still early, before noon. So I decided to return by myself to Xiantao City where we were staying to get the still camera and video camera, and have Guo Liying stay with Zhu Jingrong.

Zhu Jingrong’s son was waiting for me at the village entrance when I returned with the equipment. Only now did I have some time to take a good look at the size of the village. It’s divided into several streets. On each street there’s a row of houses of different sizes. From the end where I looked, the street appeared quite long. Economic reform has brought changes to the rural areas in the past few years. Families with able-bodied members can go to cities to work. Then they return to the village to build houses with the money they earn in the city. All houses, which have two floors, are connected to each other, with walls covered with ceramic tiles. Quite a number of them are old houses that have never gone through renovations. Low and run-down, the old houses make a sharp contrast with the new ones. Old or new, the walkways leading to the doors are all paved with cement, not dirt paths like in the old days.

Zhu Jingrong’s family lives in an old house. There are no decent-looking household items. The central room right beyond the entrance serves as a dining room. There’s one square table with a few benches. An old cabinet stands against the wall, with miscellaneous odds and ends stacked next to it. There is a room on either side of the central room—one for Zhu Jingrong, and the other for her son and daughter-in-law, where there was one bed. The refrigerator and an old television set in the son’s room are the only modern looking items in the house. The white paint on the dirt walls had completely peeled off. At the back of the central room is their kitchen. Outside is a small backyard where they plant some vegetables for themselves. One can tell at a glance that this is a poor household even by village standards.

Zhu Jingrong told us that even this old house didn’t belong to them. It is her uncle’s and her family was allowed to live in the house after her uncle moved his family to Xiantao City. She couldn’t live in her own house because she had no money for the upkeep and it had since collapsed and is no longer habitable.

Zhu Jingrong and her youngest son, Dai Jinhai.

Her youngest son didn’t look that seriously ill, but he didn’t like to talk much. He has two children. The older one is a girl who is old enough to go to work outside of the village. The younger one is a boy who’s still in school. His wife also works in Xiantao City and comes home once or twice a month. When we ate, I noticed some unusual behavior. He never sat down to eat. Instead, he walked back and forth with his food bowl in his hands. According to Zhu Jingrong, he’s much better now than when he first became ill, due to years of treatment and daily medication. But he can’t be emotionally irritated or he’ll relapse. She has endured great suffering because of his illness. She also has a daughter, who is married and lives in another village and comes back to visit her only on Chinese New Year and other holidays.

The following is an edited transcript of our conversations with Zhu Jingrong and her nephew-in-law.

You Weijie: “Next year will be the 25th anniversary of June Fourth. As mothers, our children have been gone for 25 years. We come here today hoping that we can make a record of your voice and image because as parents we’re getting older. This is the first priority. In addition, we also want to hear from you as the mother of a child who was killed for no reason at all. Please say what you would like to say.”

Zhu Jingrong: “At the time, when the school sent us the news, everyone hid it from me—they were afraid that I couldn’t take it. They hid it for a few days. Later, the school sent a telegram and it was delivered to my uncle’s house. My uncle then told me the news. As soon as I heard it, I fainted. After I came to, I didn’t want to live anymore. My child was the key member of our family, the main pillar. He was our family’s only hope. In the countryside, it wasn’t easy to provide for a child so that he could get ahead. And when he did succeed, who would have thought that such a thing would happen to him. I thought that the capital, Beijing, was the safest place. Who would have thought that going to school in Beijing would cost him his life? My child didn’t violate the law, and didn’t rob or loot. He lost his life for nothing. How could this make sense to me? I spent two whole years paralyzed in bed. I couldn’t walk. After receiving the telegram from the school, his father and a few nephews-in-law went to Beijing. They didn’t let me go. They were afraid that I wouldn’t be able to take it. They took his body from the hospital and cremated it at Babaoshan cemetery.”

You Weijie: “Where did he get shot? Where was he? Which hospital was he taken to?”

Zhu Jingrong: “He was shot in the chest. He was still alive when he was taken to the Friendship Hospital. A professor at the hospital performed the operation. He was even talking to the doctor in English on the operating table. He was a graduate student, and he and two other students had walked to the place where the martial law troops were and were shot.”

Shirt (cut open during surgery) Dai Jinping wore when he was shot.

Blue jeans Dai Jinping wore that day.

You Weijie: “It’s been 25 years. What do you ask from the country?”

Zhu Jingrong: “I believe that the government should give us an answer. It was extremely difficult for a poor family like us to raise and nurture a child to become a graduate student. I was sent to do manual labor in the countryside. I once worked as a substitute teacher at a community-run village elementary school. I didn’t make much, 18 yuan a month. It was so hard to bring up my son. I ask that the government compensate us. I must stay strong and live to the day when the government gives us an answer. We’ve already waited more than 20 years. As a mother, it is so painful for me to see other families’ children of my son’s age still alive, and my own innocent son was shot to death for no reason at all. We are old. We live day by day. I hope that the government can resolve this when we’re still alive so that we can close our eyes in peace. Otherwise, we’ll die with this injustice unredressed! We ask that the government not delay anymore. You can’t drag this out forever—so many lives lost! The People’s Liberation Army is supposed to fight invaders. How could they shoot the civilians of their own country, especially unarmed, defenseless ones? Human life is priceless. A life disappeared just like that? This is truly outrageous!”

You Weijie: “Was Dai Jinping the first in your village to get admitted to a university?”

Zhu Jingrong: “Yes, he was the first one in our village to have tested into a university. In those days, we only had one thatched cottage with two rooms. It was later blown down by the wind. When he was at school, we didn’t have money to buy paper and pens. I picked things from the trash to resell in order to buy him paper and pens. It was so hard—even just to buy paper and pens. Now, I have two grandchildren in college. If Dai Jinping had not been killed, our family would not be in this situation.”

Zhu Jingrong took out Dai Jinping’s bloodstained clothes, photos of him when he was alive, his notebooks and other possessions of his that she has kept in a trunk for more than two decades. Her daughter took away photos of Dai Jinping after he was shot, fearing that they would upset her mother.

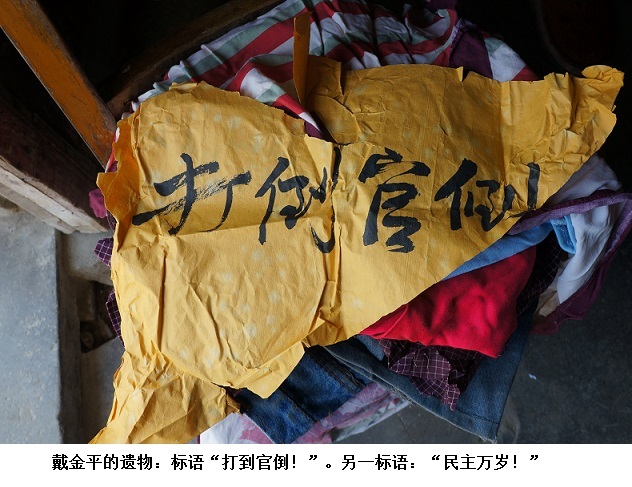

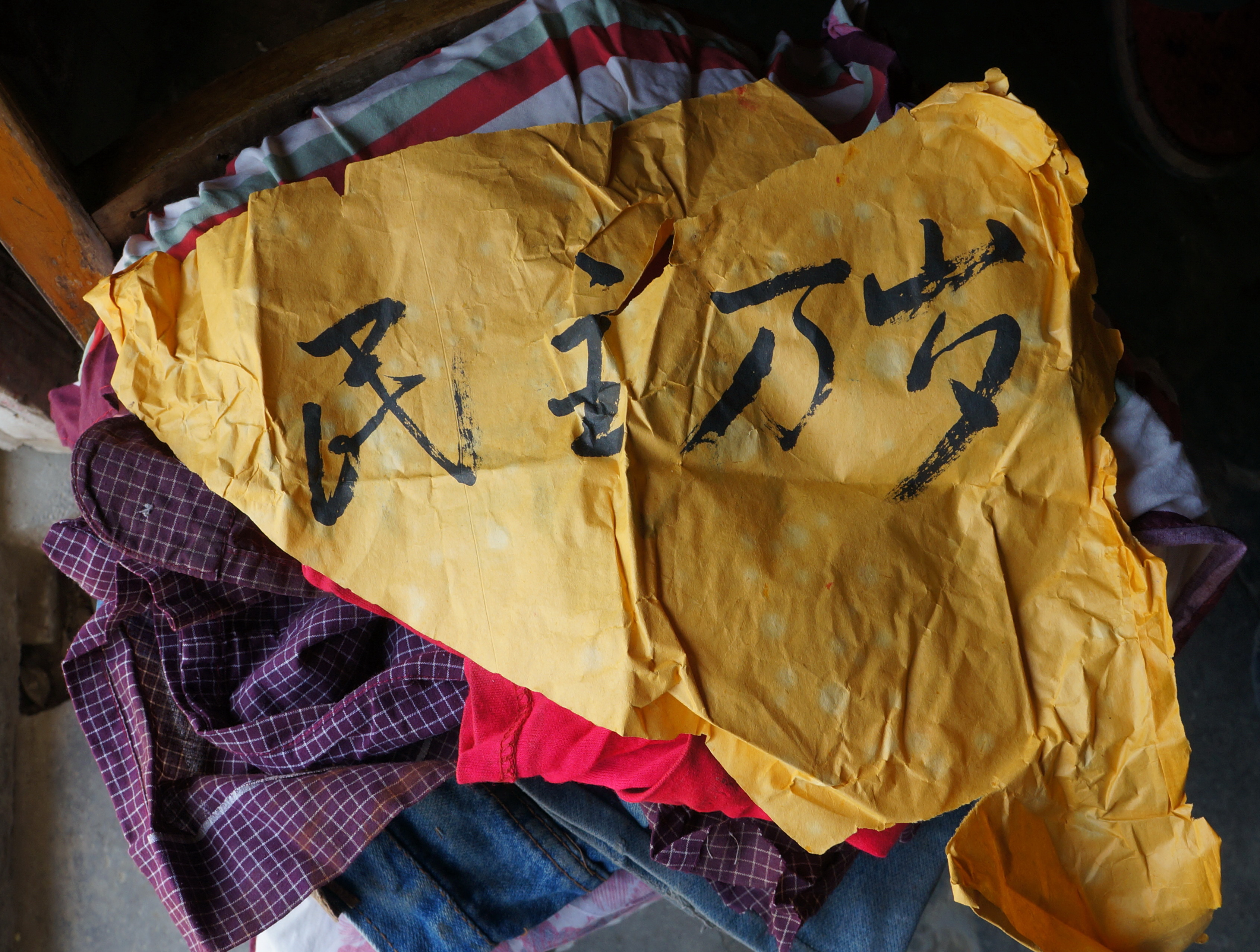

Banners used by students are now kept by family members.

A banner left by Dai Jinping: “Down with official profiteers!”

A banner left by Dai Jinping: “Long live democracy!”

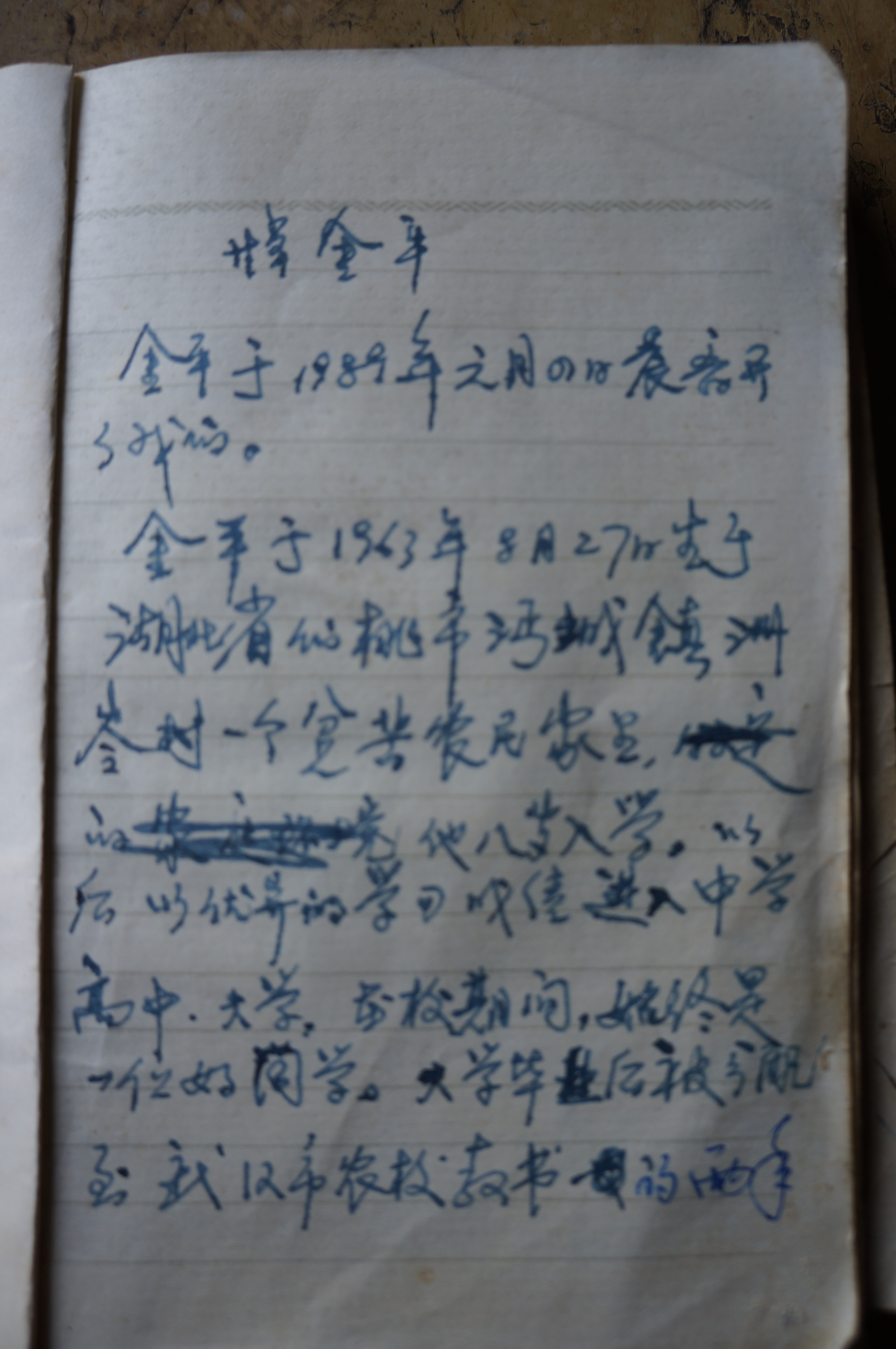

In Dai Jinping’s notebook, we saw a eulogy written by his fellow graduate student classmates in the Department of Landscape Architecture of the Agricultural University. It reads:

We mourn Jinping, who left us on June 4, 1989.

Jinping was born into a poor peasant family on August 27, 1963 in Zhouling Village, Mian Township, Xiantao City, Hubei Province. After entering elementary school at age eight, he went onto middle school, high school, and university with excellent grades. He was always a good student in school. After graduating from university he was assigned to teach at the Wuhan Vocational School of Agriculture, where he taught for approximately two years and was a good teacher. In September 1986, he was admitted to Beijing Agricultural University, where he studied for his master’s degree. He studied very hard and earned excellent grades. He had wide-ranging interests and was an ardent and thoughtful young man. He hoped that, after graduation, he could repay his parents and be of service to his motherland.

Jinping was a good classmate and good friend of ours. Our genuine friendship developed from our arduous life at school together. He worked diligently and overcame hardship to finish his graduation thesis. His conduct was good and he pursued progress, winning the admiration and praise of his supervisors and teachers. But he left us just as he was about to reap the reward of his hard work of the past three years, when his thesis of more than 10,000 characters would soon be approved, and when he was being considered as a probationary Communist Party member. His death at the prime of his life, with his genuine dedication and with goals not yet achieved, has brought us incomparable sadness. It is a true loss to the country and his family.

Rest in peace, Jinping. Your honesty and diligence set an eternal model for our university. Rest in peace, Jinping. We will always remember you. In mourning, Graduate Student Class of the Department of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Agricultural University. June 19, 1989

(Signed by ten people: names omitted)

Eulogy by classmates of Dai Jinping, written in his notebook.

Since her family members kept details of her son’s death from her, I called her nephew-in-law to learn about the actual circumstances of Dai Jinping’s death and to verify details. He was among the relatives who went to Beijing to handle the matters surrounding Dai’s death, and he also helped the family handle things at every difficult juncture.

Zhu Jingrong’s nephew-in-law: “Dai Jinping didn’t participate in the student movement before June 3, 1989. He’d been doing laboratory experiments and preparing his graduation thesis. On the evening of June 3, he spoke to his supervising professor and then got on his bike and left campus. When he arrived at Peking University, he ran into two of his classmates who were studying at Beida (abbreviated name of Peking University). The three of them went toward Chang’an Avenue. But when they heard the loudspeaker warnings telling people not to go into the streets, the two classmates turned back while Dai Jinping continued on toward Tiananmen Square. When he arrived at the back of Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum, he ran into the martial law troops and was shot three times in the chest. What really happened on the spot isn’t clear. He was taken on a flatbed tricycle to Friendship Hospital. They wanted to find the person pedaling the tricycle to learn more about what happened but couldn’t locate him.

“When Dai Jinping arrived at the hospital he was still alive. They spent more than 10 minutes trying to resuscitate him but didn’t succeed. When Jinping didn’t go back to school, his professor and the teacher in charge of his class, a doctoral student named Wang Tao, took a few classmates and went to every hospital to look for him. Finally, they found his body at the Friendship Hospital. On his person were his student ID and Beijing Agricultural University meal tickets.

“The university sent us a telegram. When we got it, his father and several of us cousins went to Beijing on June 9. We stayed at the school’s guesthouse. We didn’t tell his mother the news when we left. It was our uncle who stayed at home who later told her. We were met by the dean of the Landscape Architecture Department, Dai Jinping’s supervising professor, and the teacher in charge of his class. The school did not hold a memorial service because the situation in Beijing was very tense. The student union, on its own initiative, set up a mourning shrine in the dining hall. Many people presented floral wreaths.

“The professor who’d been supervising Dai Jinping for two years treated him like his own child. He was very angry about his death. He felt that it was extremely unjust for the government to resort to such means to handle the students and that so many innocent children were shot to death. Many teachers and students whom we didn’t know came to see us and made donations in memory of Dai Jinping. They donated approximately 6,000 yuan. The school had a very favorable assessment of Dai Jinping in its conclusion of his death. It wasn’t until June 17 that we finished with the whole procedure.

“Dai Jinping’s younger brother was attending Miancheng High School. One day, less than six months after Dai Jinping’s death, he went missing during an evening study session. The school couldn't find him so they notified the family. We mobilized many relatives to search for him. We looked for two days and finally found him 50 kilometers away in Changdangkou Township. He was wandering aimlessly in the street. He hadn’t eaten for two days and was covered with dirt. He was diagnosed as having developed schizophrenia. He was unable to study anymore and had to quit school. A lot of money was spent treating his illness. Now his condition is controlled by medications. He has completely lost his ability to work.

“I handled matters for Dai Jinping’s father after he died. So I know about the situation. After his older son was killed, his younger son became mentally ill, and his wife became sick, he had to shoulder the burden of supporting the family all by himself. He decided to go work in the city. In 1998 he started using a shoulder pole with ropes to do delivery work on Hanzheng Street in Wuhan. He’d only worked for less than a year before he lost his life for one yuan. A merchant selling New Year’s paintings agreed on a price with him for a delivery. But after he made the delivery, the merchant shortchanged him one yuan. They started arguing and the merchant used his knee to hit Dai Congde’s lower body very hard. The injury killed him.”

We are filled with sympathy for Zhu Jingrong’s family. All of what it has suffered is the result of the unprecedented brutality of the June Fourth massacre.

Imagine the kind of sufferings this mother and wife had to endure, beset by blow after cruel blow. But she is also a strong woman. She knew that she still had two children who needed her and she must conquer her sadness and her illness. If she were gone, her two children would become orphans. Her ill younger son needed her most. She has done it. She has continued to provide love for them. She has persevered—in the hope of seeing justice for her son someday.

© All Rights Reserved. For permission to reprint articles, please send requests to: communications@hrichina.org.

You Weijie (尤维洁) and Guo Liying (郭丽英) are members of the Tiananmen Mothers.

Dai Jinping (戴金平), 27, a graduate student at the Landscape Architecture Department of Beijing Agricultural University. Shot in the chest near Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum in Tiananmen Square on the night of June 3, 1989. He was killed at around 11 p.m. His family members saw his body around June 10 in the morgue of the Friendship Hospital in southwest Beijing. The school gave them 2,000 yuan for his funeral expenses.

Dai Jinping (戴金平), 27, a graduate student at the Landscape Architecture Department of Beijing Agricultural University. Shot in the chest near Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum in Tiananmen Square on the night of June 3, 1989. He was killed at around 11 p.m. His family members saw his body around June 10 in the morgue of the Friendship Hospital in southwest Beijing. The school gave them 2,000 yuan for his funeral expenses.

Previously Issued