[Translation by Human Rights in China]

In the afternoon, on the way back from Kong Weizhen’s house, before even reaching the gate of Wuhan Institute of Technology, Guo Liying and I saw Qi Guoxiang (齐国香) walking to welcome us. She is a warm-hearted, sincere person who is helpful to others. Being around her gives you a kind of intimate, close feeling.

On the way to her house, Qi Guoxiang told us that the news of their son’s death was like a bolt from the blue. Everyone in the family was stunned. There was no way for them to get to Beijing to handle the funeral preparations so Qi Guoxiang’s second eldest sister, who worked at Xi’an Jiaotong University, went to Beijing on the family’s behalf. The sister did not let Qi and her husband look at their child’s belongings. She kept them in her home for them.

When we arrived at Qi Guoxiang’s home, her husband, Liu Ren’an (刘仁安), was waiting for us. He is of medium height, with grizzled hair and a kind face. He is an intellectual, very down to earth. His health is not very good. He has serious heart disease, and his fungal sinusitis cannot be operated on because of his heart condition. He is often dizzy, and the sinusitis has already begun to affect his sight and hearing. Because of his poor health, he rarely goes downstairs. All the housework is done by his wife.

Qi Guoxiang and Liu Ren'an.

After we exchanged greetings, we started with 1989 and how their second son, Liu Hongtao (刘洪涛), died. In fact, we could not bear making all these parents talk about their children’s death that year, causing them to tear open those private wounds inside their hearts once more. It’s really inhumane. But in order to document history, we had to do it. Thus, each time we left a family after conducting an interview, we would say to the family members: please let go of this sadness, take care of yourself, and live well; we are certain you will see justice done for your child one day!

The following is a record of our visit with Qi Guoxiang and Liu Ren’an.

Qi Guoxiang started first: “At the start of the 1989 Democracy Movement, we wrote to our son and asked him to study hard. He wrote back saying that he was a college student of China and that ‘the rise and fall of the nation concerned every ordinary man. We are expressing our cherished wishes for the country. It is our responsibility.’ In Tiananmen Square, he was responsible for maintaining order. Their responsibility, on the ‘second line,’ was to ensure the safety of those who were on the frontline—the students on hunger strike. In the square, he barely slept, and eating also became a problem.”

Liu Ren’an continued: “I am fairly conservative because I am a bit older and lived through the Anti-Rightist Movement and the Cultural Revolution. I wrote to him, saying ‘I can understand your feelings, but you don’t understand the state of the country. Some things cannot be solved all at once. It would take a shared consciousness in order for them to be fixed.’ He couldn’t understand this kind of talk. He wrote to me and said, ‘If everyone waits for others to act and reaps the benefits of others’ labor, how could change happen?’ He gave an example: if during a march, everyone is a spectator, there’d be no one to march. I think that makes sense. From the beginning of the student movement, he participated in the marches.”

Qi Guoxiang: “We both didn’t know the real situation in Beijing. On May 28, one of his middle school classmates came back with him for two days. Hongtao’s father was very unhappy to see his son come back because he thought he should be studying. He said he saw on TV that the schools had already issued a notification that classes would be resumed. At that time, I argued with his father. I didn’t want Hongtao to go back. After we fought, our son left. On the night of June 3, in order to stop the military trucks from getting to Tiananmen Square, he and others blocked the road near the Cultural Palace of Nationalities. He was relatively tall, about 1.76m [5’8”], and was shot in both legs. Students from other schools and residents who were at the scene took him to the Postal and Telecommunications Hospital. My second eldest sister, when she came back from Beijing afterwards, told me that she had heard the authorities’ ordered the hospital not to save him. She heard that the doctor asked him which school he went to. At that point, he was still conscious and pulled his student ID card from his pocket to give to the doctor. They did not save him so he died.”

You Weijie: “When did you find out?”

Qi Guoxiang and Liu Ren’an, taking turns: “On the 5th, the secretary of our school’s core curriculum department notified us. He told us ‘your child was hurt. I will accompany you to Beijing.’ Later, a close colleague told us, Hongtao had already died. When I heard this, I could not even walk.”

Qi Guoxiang: “He was born in 1971. He started elementary school at age six, and finished in five years. He was admitted to university at age 17, in the entering class of 1988. His gaokao[1] score was 586.”

Liu Ren’an: “Fifty points higher than Tsinghua’s minimum test score requirement.”

The couple told us his mathematics and English scores were especially good. He was a natural at science. They were very proud. They originally didn’t want him to go to Beijing for university, but to Xi’an Jiaotong University instead, because his aunt was there and could take care of him. But he didn’t agree. He liked Beijing and wanted to go to a university there. He himself chose the schools to apply to. He told his parents optical engineering was the technology of the 21st century.

Qi Guoxiang: “This child was always smart, honest, and compassionate. He never fought with others. His relationships with his classmates were especially good. One time, a classmate broke Hongtao’s arm, but Hongtao never said a thing to us. Later when we found out his arm was broken, we asked him how it happened, but he wouldn’t give a reason. All of his classmates, whether in middle school or university, liked him a lot.

You Weijie: “Which university did you graduate from?”

Qi Guoxiang: “We both graduated from Nankai University’s Chemistry Department in 1966. We were classmates.”

In 1968, the couple was sent to work at a special metal manufacturing factory under the Ministry of Metallurgy in Zunyi, Guizhou Province. The factory, which was a classified workplace, was part of Lin Biao’s[2] No. 721 engineering project. That was during the Cultural Revolution. They were sent to work in a workshop, and received “workers-peasants-soldiers (proletariat) re-education.” In 1978, because of Liu Ren’an’s failing health, they finally left Zunyi to return to their home in Hubei to teach at the Wuhan Institute of Technology.

They had three sons in total. The eldest was not very healthy as a child, and currently lives in the United States. Because of what happened to Hongtao—their second child—the couple was very upset so they did not put a lot of energy into raising their third child. He only tested into his parents’ university, Wuhan Institute of Technology, and currently works in Chongqing, Sichuan Province, because his wife is from Chongqing. At present, Liu Ren’an and Qi Guoxiang live by themselves.

The couple cared most about Hongtao. When he was little, they sent the eldest child and the youngest child to live with Qi Guoxiang’s parents in Hebei Province because they were busy with work and had no time to care for three children. Hongtao was fairly strong and able to take care of himself from the age of just over two. At that time, they were still in Zunyi. Hongtao was his father’s favorite child.

When we talked about Hongtao as a child, Qi Guoxiang couldn’t help crying. Choked with emotion, she told us that her son would follow them around when he was just over two years old. They did not put him in a nursery school. They locked him in the house when they went to work. Approaching the time when they would come home, Hongtao would lean against the window sill, anxiously staring out, waiting for them to return. As soon as they got home, Hongtao would run out excitedly. Because he was little, he would make a big mess in the house.

Hongtao was always an outstanding child, whether in elementary school or middle school. His teachers and classmates all liked him very much. He took his work seriously. In middle school, he was the representative of his biology class. His class had two pet rabbits, which he was responsible for feeding. Once during a heavy snow storm, his parents waited for him for a long time to get home. They were very worried. When he finally got home, they found out that he had gone to look for grass for the rabbits. His footprints were all over the snow.

Liu Ren’an: “In these 25 years, there has not been one moment when I didn’t miss him. I don’t dare look at his photo. If I do, my heart breaks. I just can’t bear it.”

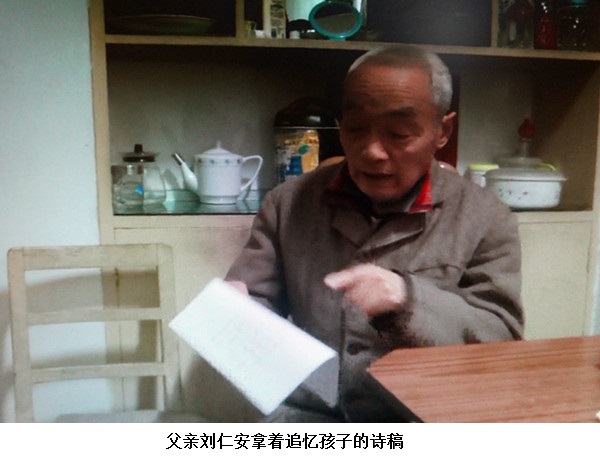

Father Liu Ren’an looking back at the memorial essay about his son.

Qi Guoxiang, crying: “My second sister said to me, ‘Let’s keep Hongtao’s photo in my house. Don’t look at it. If you were to look at it, it would be unbearable for you—it would drain your emotional strength; in your heart, Hongtao is still energetic and alive.’ I remember clearly, in 1989, he came back on May 28 and left on the 30th. I remember very clearly what he looked like as he left.”

Out of all the families we visited, this was the only one that did not have a photo of their child. In their hearts, the image of their child will forever be fixed on the day of May 30, 1989—the day he left to go back to Beijing. But they still can’t help hoping that, one day, Hongtao will stand before them, alive and ready to serve them filially.

Liu Ren’an stood up and took out the memorial essay about his son. He said for the 25th anniversary of June Fourth, he wants to mail this essay to Ding [Zilin][3]. He only read a few sentences before he was choked with tears. Men don’t cry easily, and do so only when they are truly hurt. In the tears of this father, one could see the weight of his sorrow.

Then, Qi Guoxiang brought out a small bundle and opened it. Inside were several neatly-folded articles of clothing.

Liu Hongtao’s mother, Qi Guoxiang, with clothes she had made for her son.

Sobbing, Qi Guoxiang took out piece after piece and said to us: “I made all of these clothes for him with my own hands. Our family’s economic situation was tight so I made all my children’s clothes. And I pieced together bits of cloth to make this book bag. I hoped that they would study hard. My son was never picky. Look at this patch. I patched this for him. He never said anything. How I miss my son! When my son’s ashes were brought back, I did not dare look at them or his photos. After keeping them for a while, I scattered his ashes in the Yangtze—so that he can follow the waves to see the free world!

“For the past 25 years, I have not slept well a single night. Every time I dream, I dream that my son came back. I hug him and say ‘Hongtao, you came back! You didn’t die!’ Then I wake up and see that it’s all not true. He loved this country! And then he was dead. Where are we to go to voice this injustice! Where is the law of heaven! I believe that there’ll be no good end for murderers!”

Liu Ren’an: “I don’t hate other people. I just hate Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng. Deng Xiaoping was the executioner! I like history. There is no other time in Chinese history when the military massacred ordinary civilians during peacetime. The students were unarmed and defenseless. They held nothing in their hands. How could they use the military to crackdown on them? From childhood to university, my son had always received high marks from teachers and classmates alike. If he had had anything in his hand to fight back, then you had a reason to kill. But he had nothing—so what grounds do you have to shoot him dead! My son sacrificed his life for the country. Don’t think we will forget. We will absolutely not forget. It’s only that we don’t want to bring up this heartbreaking matter publicly. It’s been 25 years, not a single person in the country has the courage to take responsibility.”

You Weijie: “After June Fourth, tell us how the last 25 years have been.”

Qi Guoxiang: “The school has been very good to us—sympathetic and caring. Our convictions in life changed following the death of our child. We didn’t want to be considered for professorship or other high-level jobs anymore. We retired early. The State Security Bureau sent people to monitor us. One time during the 1990s, when my mother was over 90 years old, I returned to my ancestral home in Hebei. Just as I arrived home, the people from village’s State Security authority came to question me. Later, a relative who was informed by the village’s State Security authority that I was being monitored came to ask me about it. I said it was only because Hongtao was shot dead during June Fourth.

“In 2000, we wanted to go to the United States to take care of our eldest son’s child. The school provided documentation to verify our identities, and agreed to arrange for the relevant work unit to help us apply for our passports. The procedure usually takes 15 work days. When I went to get my passport, they didn’t have it. I asked what was going on, and they said it was an order from higher up. Again, I did nothing illegal, and the school gave me documentation. They had no reason to not issue me a passport. We negotiated and only then, and after several more days, did they give me my passport.

“I went to Beijing to obtain a visa. Just as I got on the train and put my luggage away, three people came to ask me where I was going, and looked at my ID card. One of them said to me, you’d better be careful in Beijing. Then I knew who they were and who sent them. They came to see which train car and seat I was in. After they left, I switched cars with someone so that I wouldn’t be tailed after getting to Beijing.”

Liu Ren’an: “Our child was shot to death, and still now they do not admit their guilt. We don’t have our freedom. However, nothing like that ever happened again.”

You Weijie: “In the international community, we, families of victims, are recognized as the Tiananmen Mothers. I also know that you have participated as signers of our petitions, and unconditionally supported every action by the families in Beijing. Over these many years, we have steadfastly maintained our three requests: truth, accountability, and compensation. Now we’d like to hear your thoughts on these three requests.”

Qi Guoxiang: “We absolutely agree! There is irrefutable evidence of this major incident. Of course they need to make public the truth of the shooting and killing—truth that is based on facts—chase down the culprits, and investigate and hold responsible the actors behind the scenes. This is something that they can’t get around. We also ask the government for compensation. That year, the Beijing Institute of Technology gave us 1,000 yuan for the burial. Our son was shot dead for no reason. The government should compensate us.”

Together with the couple, we talked about Taiwan. After Taiwan democratized in 1995, the elected president Li Denghui, on behalf of the Kuomintang, publicly apologized to the Taiwanese people for the 1947 “2-28 Incident”[4] in Taiwan. This apology did not cause any social turmoil. The masses have sympathetic hearts. As long as you truthfully handle matters in the interest of the people, then you will obtain the support of the masses. Those with morals will flourish; those who lose their way will perish. Now through democratic elections, isn’t the Kuomintang, led by President Ma Ying-jeou, in power again? Taiwan’s regime is not a dictatorship—it has to subject itself to the supervision by all people, rule according to a platform, and be democratically elected. If you cannot handle affairs in the interest of the people, you should step down.

Liu Ren'an and Qi Guoxiang with You Weijie and Guo Liying.

The 1989 student movement was not about overthrowing the Communist Party. It was an expression of the hope for reform and opposition to the abuse of power and corruption. It raised questions about social inequalities. It wanted government officials to practice clean politics. All these led to massive reactions from all walks of life, even support from people all over the country. Then the movement broadened to include the appeal for democracy, freedom, press freedom, and rights of citizens. If the Communist party were an open-minded political party, it would have used the coalesced forces of society to closely examine the problems in its governance. As that session of government was questioned by the people, it demonstrated that the government’s leaders had lost the trust of the common people. Since they could not handle affairs in the interest of the people, they should have stepped down. Deng Xiaoping heard what he wanted to hear and used the military to crackdown on the students. This was his crime against the Chinese people. However, I hope that Xi Jinping, now in office, will provide an explanation and resolution to the victims’ families for that crime.

These two seniors are good-hearted. We hope that they will let go of the sorrow in their hearts, live happily, and live to the day when their requests are met, so that they can leave this world without regret.

Translator's Notes:

[1] Gaokao is the National Higher Education Entrance Examination required for undergraduate admission at most of the universities in China.

[2] Lin Biao was vice premier of China, 1964-1971.

[3] A former spokesperson of the Tiananmen Mothers.

[4] The “2-28 Incident” was a violent crackdown on February 28, 1947, by the Kuomintang—which had taken control of Taiwan after the Second World War—on local Taiwanese anti-government protestors. The massacre resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of civilians. The episode is commonly thought of as the beginning of the “White Terror” period in Taiwan, which resulted in the persecution of thousands of dissidents in Taiwan.

© All Rights Reserved. For permission to reprint articles, please send requests to: communications@hrichina.org.

You Weijie (尤维洁) and Guo Liying (郭丽英) are members of the Tiananmen Mothers.

The story of Liu Hongtao (刘洪涛), 18, a student of optical engineering at the Beijing Institute of Technology, in the entering class of 1988 (section No. 40882). He was shot in both legs near the Cultural Palace of Nationalities and died in the early hours of June 4, 1989. His body was recovered at the Beijing Postal and Telecommunications Hospital.

Previously Issued