When Chinese tax authorities went after artist-cum-activist Ai Weiwei in November 2011 for alleged tax fraud, many Chinese saw the allegations as a transparent attempt to muzzle the popular social and political critic, who had taken up a number of causes in recent years.

So it came as no surprise when everyday Chinese around the country sprang to his defense, offering to repay his activism with donations to cover a huge fine his company had been hit with.

Ai Weiwei crossed the line from art to politics in the wake of the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, when thousands of children lost their lives when their schools collapsed, apparently because of substandard—“tofu-dreg”—construction. While the government ignored what had happened, and police refused to give numbers and names of the victims, Ai sent volunteers door-to-door to gather a list of names. Later, he began to list the 5,196 names of the children on his Twitter account. The names are now on the wall of his Beijing studio.

The earthquake now influences Ai’s work. In 2009 he covered the façade of the Haus der Kunst museum in Munich with 9,000 children’s knapsacks spelling out the words of a victim’s mother—“She lived happily for seven years in this world”—in Chinese characters. This year the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., arranged Ai’s first major U.S. show, although the Chinese government refused him permission to leave China to attend the show. The first wall encountered in the show is covered with the names of 5,196 children who were killed in the earthquake. Another piece is simply a recording of their names being read out loud. The exhibit also includes steel rods from the earthquake area. Some of the rods are copies, mimicking the distorted shapes of the originals, while others have been painstakingly straightened.

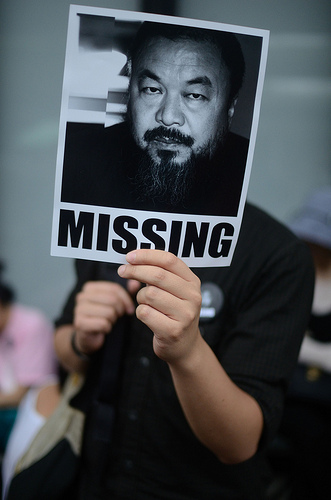

Ai was arrested at the Beijing Capital Airport on April 3, 2011 as he was about to board a plane for Hong Kong, and he spent the next 81 days in police custody. Four days after his detention, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said he’d been detained on suspicion of committing economic crimes. His supporters, however, knew the reason was actually political.

Right from the beginning, the world-renowned artist’s case attracted a degree of international attention that few other enemies of the state have enjoyed. The foreign media leapt on the arrest of China’s most famous artist. On April 24, 2,000 artists and other citizens in Hong Kong protested the detention and called for Ai’s release. Prominent artists from around the world signed petitions calling for his release.

There were numerous holes in the government’s case. Fake Culture Ltd. is not in Ai’s name, but rather in the name of Ai’s wife, Lu Qing. Chinese authorities refused to provide evidence of the alleged tax evasion, his account books were confiscated, and his manager and accountant were forbidden to see him. When his appeal opened, Ai was not allowed to attend his own hearing.

On November 1, tax authorities charged the company with tax fraud and hit it with a 15 million yuan fine (about $2.38 million) that would have to be paid within 15 days. As soon as the news became known, people around China began sending him money to help cover the 8.45 million yuan bond (about $1.34 million), which would allow him to challenge the charges. Ai, moved by the public support, went on the offensive himself on November 4, launching a “Be a Creditor of Ai Weiwei” campaign online, providing his bank account number for citizens to become his creditors.

“Within one week, we received more than 9 million yuan from 30,000 young people on the Internet” Ai told me last summer during an interview. “That was like a miracle. This has never happened before in China. It was like a social movement.”

The money has come via bank and postal transfers, AliPay, the Chinese version of PayPal, and less traditional financial channels.

“Many people made money into paper airplanes and threw them over the wall into the yard, and in the morning, we would find a lot of money on the ground,” he said beaming. “It was just unbelievable.”

Some sent money over the wall of his art studio on the outskirts of Beijing rolled into balls, while others wrapped cash around pieces of fruit. Some even tossed cash in the cat’s eating bowl. Ai’s staff were surprised when they saw the cat playing with something, finally realizing it was money that had been thrown over the compound wall overnight.

Ai said many of the donors were young Chinese in their 30s. Liu Yanping, a volunteer, was quoted as saying that many of the donations were accompanied by messages of support, such as "Brother, let me be your creditor."

Many messages accompanying the donations included veiled political references.

"Don't be anxious, I'll wait for freedom to come, you return it to me in a new currency," one donor wrote to Ai in a note described by Reuters, alluding to the image of former Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong on China's banknotes.

Another supporter donated 289.64 yuan—in reference to the June 4, 1989, armed crackdown in Beijing's Tiananmen Square.

Ai described the donations as Chinese people—who are restricted from casting ballots in elections—voting with their money.

Surprised by the wide-spread grassroots support for Ai, the state-run Global Times newspaper said that the artist could be charged with "illegal fundraising" for accepting contributions for his tax bill. In the report, the newspaper said donators only represented a very small part of China’s population. And state censors began to ban any words related to Ai on the Internet, including Ai Weiwei, Ai creditor, loans for Ai, and even the word “donations.”

On November 16, Ai used the money he raised to pay the bond. He was prevented from attending his own appeal, which he lost. Officials in late September 2012 said that they were revoking Fake’s business license because the company did not comply with annual registration regulations. Ai said the company was not able to do this because police had confiscated all the company’s documents and its business seal when Ai was detained last year.

On the positive side, the shutting down of the company could mean that Fake would not have to pay the remainder of the tax fine levied against it. Ai surmised that officials were too embarrassed to collect the money following the nationwide outpouring of support for him, afraid the movement would blow up again and spread wider.

Paul Mooney (慕亦仁) is an American freelance journalist and has reported on China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong since 1985. At various times, he has been on staff at Newsweek, the Far Eastern Economic Review, and the South China Morning Post. He has lived in Beijing since 1994.