The Beijing Municipal No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court, Criminal Justice Court No. 11

The Honorable Presiding Judge and Judicial Officers:

We have been retained by Liu Xiaobo, the defendant in this case, and designated by the Beijing Mo Shaoping Law Firm, to act as the defense counsel on behalf of the defendant Liu Xiaobo, [who has been] charged with the crime of “inciting subversion of state power.” We will faithfully carry out the duties stipulated in Article 35 of the Criminal Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter referred to as the Criminal Procedure Law) and defend the legal rights and interests of Liu Xiaobo in accordance with the law. After being retained, we met with Liu Xiaobo many times, reviewed in detail the evidentiary material that the Procuratorate sent to the Court, and have just participated in the court investigation, court hearing, and the questioning of witnesses, which have allowed us to further our understanding of the true circumstances of this case. Based on our respect for truth and evidence, and in accordance with the relevant provisions of the law, we put forward the following defense opinions, to be used as a reference by the collegiate bench during its deliberations.

The defense counsel contend that the charges for the crime of inciting subversion of state power against defendant Liu Xiaobo brought by the Beijing Municipal People’s Procuratorate Branch No. 1 (hereinafter referred to as “Prosecuting Organ”) in the Branch No. 1 Beijing Criminal Indictment (2009) 247 (hereinafter referred to as “Indictment”) cannot be established.

The defense counsel contend that there is no difference of opinion between the prosecution and the defense on the basic facts of the case (namely, the six articles listed in the Indictment, such as “The CPC’s Dictatorial Patriotism,” published on websites such as those of Observe China and the Chinese edition of the BBC, were written by Liu Xiaobo, and Liu Xiaobo, as one of the drafters of Charter 08, published Charter 08 on the overseas websites of Democratic China [www.minzhuzhongguo.org] and Independent Chinese Pen Center [www.chinesepen.org] (the only point of objection to the facts is that Liu Xiaobo collected only over 70 signatures, not “more than 300” as charged by the Indictment). The main difference of opinion between prosecution and defense in this case lies in the applicability of law, namely, whether the articles Liu Xiaobo published and Charter 08 that he drafted fall in the category of the citizens’ [rights to] freedom of speech and expression, or whether they constitute the crime of inciting subversion of state power. In addition, the defense counsel contend that serious procedural flaws exist in the course of investigation, indictment hearings, and the trial of this case. Following is an elaboration of the details:

I. The existing evidence cannot prove Liu Xiaobo’s subjective intent to incite subversion of state power.

When we apply this concretely to this case [we contend that]:

The Indictment has not done a comprehensive job of gathering, screening, and establishing the evidence that proves the guilt or innocence of Liu Xiaobo; namely, it did not analyze and judge in a comprehensive and objective manner the 499 articles that Liu Xiaobo has published on the Internet since 2005. Rather, it established Liu Xiaobo’s intent to incite subversion of state power solely on the basis of a few isolated phrases from six of his articles published on the Internet and Charter 08. This, obviously, does not conform to the principles for collecting evidence [outlined] in our country’s Criminal Procedure Law, nor does it meet the requirement of “proof beyond reasonable doubt.” For, even in the six articles identified by the Indictment as having “incited subversion of state power,” there are words and sentences that abundantly reflect Liu Xiaobo’s subjective goodwill. For example, in his article “Changing the Regime by Changing Society,” he says that “the non-violent rights defense movement does not aim to seize political power, but is committed to building a humane society where one can live with dignity.”

II. The charges against Liu Xiaobo in the Indictment are too “sweeping” and “take things out of context.”

III. The charges in the Indictment have blurred the boundaries between citizens’ freedom of speech and criminal offense.

The defense counsel contend: the articles written by Liu Xiaobo merely voice certain caustic and intense criticisms, which ought to fall under the category of free speech, and free speech is a basic human right enjoyed by citizens according to the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China(hereinafter referred to as the Constitution) and the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Article 35 of the Constitution stipulates: “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration”; Article 41 of the Constitution stipulates: “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China have the right to criticize and make suggestions regarding any state organ or functionary”; Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stipulates: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

The defense counsel contend: the personal views and opinions Liu Xiaobo, as a Chinese citizen, holds regarding the ruling Communist Party of China and the related political system give no cause for reproach. Even if the critical opinions published by Liu Xiaobo directed at the Communist Party of China and state organs prove to be wrong, they still fall under the category of a citizen’s freedom of speech. He is exercising his right to free speech conferred by the Constitution, and this exercise should not be held as a crime of inciting subversion of state power.

As stated above, writing and publishing articles fall under the category of free speech. Although the freedom of speech cannot be violated and stripped away under normal circumstances, if it directly endangers national security, it can be banned. This is the legal basis on which the Criminal Law stipulates the crime of inciting subversion of state power. However, the criteria to determine whether a certain expression of opinion constitutes the crime of endangering national security should be strictly limited, otherwise, such determination may violate human rights. Presently, Principle 6 of the internationally-recognized Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Freedom of Expression and Access to Information, provides that: “Expression may be punished as a threat to national security only if a government can demonstrate that: 1) the expression is intended to incite imminent violence; 2) it is likely to incite such violence; and 3) there is a direct and immediate connection between the expression and the likelihood or occurrence of such violence.” This principle has been summed up as the “real and imminent threat” principle, namely, only when an expression of opinion constitutes a “real and imminent threat” to national security can it constitute a criminal offense. In the present case, there are no words or phrases in the articles written by Liu Xiaobo that incite immediate acts of violence, nor can they objectively induce such acts of violence (all articles written by Liu Xiaobo are published on overseas websites and cannot be accessed in China at all unless through the use of special methods). Quite the opposite, the gradual reform by “peaceful,” “rational,” and “non-violent” means advocated in Liu Xiaobo’s articles quite obviously does not constitute a real and imminent threat to national security and therefore should not be treated as a crime.

The dictionary definition of “rumor-mongering” is “fabricating information and confusing the masses in order to achieve a certain purpose.” The dictionary definition of “slander” is “making up stories out of nothing and speaking ill of another person in order to damage his or her reputation; smearing.” The dictionary definition of “smear” is “fabricating facts to damage another person’s reputation.” (See Xiandai Hanyu Cidian [Modern Dictionary of Chinese Language], January 1983, 2nd edition, page 1443, page 315, and page 1211, respectively.) In short, “making up stories and fabricating facts out of nothing” is the common meaning of all these three terms: “rumor-mongering,” “slander,” and “smear.” In other words, “rumor-mongering,” “slander,” and “smear” all involve judgment of facts and veracity of facts, but the prosecution has no evidence to prove that the facts set forth in Liu Xiaobo’s articles are fabricated.

What should be noted here is that the values and ideas in Charter 08 are consistent with the ideas in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. For example, the statements related to freedom, human rights, and equality in Charter 08 can be found in the provisions of Article 1, Article 2, and Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as in the provisions of Article 6, Article 9, Article 12, Article 14, Article 16, Article 17, Article 18, Article 19, Article 22, Article 25, and Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. (It should be emphasized that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is one of the most important United Nations official documents and that the People’s Republic of China as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council cannot but endorse the ideas in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Chinese government signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights more than a decade ago.) Not only do the ideas espoused by Charter 08 not violate the Constitution, rather, they are in accordance with many of the Constitution’s provisions. For example, [the concept of] judicial independence can be found in Article 126 of the Constitution; human rights guarantees in Article 33 (3); election of public officials in Article 3 (2); freedom of association, of assembly, and of speech in Article 35; freedom of religion in Article 36; property protection in Article 13; social guarantees in Articles 43, 44, and 45; environmental protection in Article 26, etc. The viewpoints charged in the Indictment—“abolish the privilege of one-party monopoly on power” and “establish the Federal Republic of China under the framework of a democratic and constitutional government”—were not at all initiated by Liu Xiaobo. They are consistent with the political positions of the Communist Party of China and its principal leaders, such as Mao Zedong and Liu Shaoqi. In his article, “New- Democratic Constitutional Government,” Mao Zedong pointed out, “Just as everyone should share what food there is, so there should be no monopoly of power by a single party, group or class.”3 In a March 30, 1946, Xinhua Daily editorial, as well as in his article “One-Party Monopoly Leads to Widespread Disasters,” Liu Shaoqi said, “One-party rule is anti-democratic; the Communist Party decidedly does not engage in one-party dictatorship” (Liu Shaoqi, Liu Shaoqi xuanji, Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1981, Volume 1, pages 172–176). The Declaration of the Second National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly calls for “using a free federal system to unify China proper, Mongolia, Tibet, and Muslim Xinjiang and establishing the Federal Republic of China.” Is it possible that when the Communist Party of China and its principal leaders oppose one-party dictatorship and call for the establishment of a federal republic, they are great, glorious, and correct, but when Liu Xiaobo and others advocate such positions they are doomed to the misfortune of imprisonment?

Based on the principles of “no crime can be committed, and no punishment can be imposed, without an existing penal law” and “proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” one should not hold that Liu Xiaobo’s [actions] constitute the crime of inciting subversion of state power.

Therefore, the defense counsel contend that before the National People’s Congress and its Standing Committee, as well as the Two Supremes, make legislative or judicial explanations, based on the principle of “no crime can be committed, and no punishment can be imposed, without an existing penal law,” Liu Xiaobo should not be held guilty and punished.

IV. There were significant flaws in the investigation, procuracy review and indictment, and trial processes.

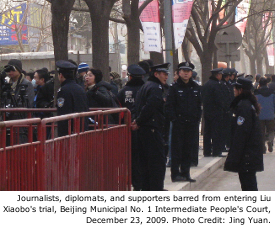

Around 2:30 p.m. on December 20, 2009 (Sunday), the defense counsel for this case received a phone call from the judge assigned to this case, saying that the trial would take place in Courtroom No. 23 at 9:00 a.m. on December 23, 2009 (Wednesday).

Based on Article 151, Section 1(4) of the Criminal Procedure Law, after a People’s Court has decided to open a trial, it should deliver written notice of the trial to the defense counsel no later than three days before the opening of the trial. The “three days” should be understood as an interval of three days, as three full days. The day when the trial opens and the day of the notice should be excluded from the count. Obviously, the time between 2:30 p.m. on Sunday, December 20 and 9:00 a.m. on Wednesday, December 23 does not amount to three full days.

During the trial session, the counsel presented to the court documents related to how the Communist Party of China and its leaders consistently opposed the one-party dictatorship and advocated the establishment of a federal republic to prove that charges against Liu Xiaobo in the Indictment cannot be established. However, the presiding judge denied cross-examination on the grounds that the prosecutor did not have time to prepare for the cross-examination.

The defense counsel contend that: 1) If the prosecutor needs to make necessary preparations for the cross-examination of evidence presented by the defense counsel to the court (before the trial, the defense counsel already communicated a brief explanation of the said evidence to the prosecutor), according to the provisions of Article 155 of The Explanations of the Supreme People’s Court on Some Issues Concerning the Implementation of the Criminal Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China, the court should adjourn and, according to the specific circumstances, allocate enough time for the prosecution to prepare; it cannot deny cross examination. The above-mentioned action by the presiding judge had no legal basis; 2) In terms of jurisprudence, the principle for collecting evidence in a criminal proceeding is “to exclude all reasonable doubt.” As long as the evidence submitted by the defense constitutes a “reasonable doubt,” regardless of when it is presented to the court, it should be cross-examined; it cannot be rejected.

Prior to the start of the court debate, the presiding judge requested that the defendant and his counsel speak no longer than the prosecutor, and then, [as the arguments started] proceeded by looking at his watch to time them. Since the law stipulates that the prosecutor delivers his indicting statement first, this in effect created a situation where the prosecutor controlled the speaking time of the defendant and his defense counsel. (If, for instance, the prosecutor only delivers one sentence, such as, “We ask the court to severely punish the defendant,” which might only take a few seconds, how are the defendant and his defense counsel to conduct the defense?)

The defense counsel contend that: 1) There is no legal basis for the presiding judge to set in advance a limit on the speaking time for the defendant and his defense counsel; 2) In terms of jurisprudence, the above-mentioned action by the presiding judge constitutes a violation of the defendant’s and his defense counsel’s right of defense; 3) Compared to the defendant, the prosecuting organ is clearly the more powerful party. Allocating the same amount of speaking time given the powerful party to the defendant and his defense counsel is seemingly fair, but it is in essence unfair.

Based on the provisions of Article 160 of the Criminal Procedure Law, after the presiding judge declares the conclusion of the court debate, the defendant shall have the right to make a final statement. When the trial of this case entered the final statement stage, the presiding judge repeatedly interrupted Liu Xiaobo’s final statement. For example, when Liu Xiaobo said that the path of his thinking had reached a turning point in June 1989, the presiding judge interrupted him by saying: That involves the June Fourth Incident; there is no need to talk about it. In fact, Liu Xiaobo had merely mentioned it as a time reference. His statement did not touch upon the June Fourth Incident. On the other hand, even if Liu Xiaobo’s statement really “involved” the June Fourth Incident, there was no reason for the sudden interruption.

The Honorable Presiding Judge and Judges,

Our country is in the process of steadily improving the rule of law. During this process, it is perfectly normal for there to be a difference in opinion on some issues, and particularly so when it comes to dealing with certain questions of guilt and innocence. But the defense counsel firmly insist that a verdict that contributes to the respect for and guarantee of basic human rights, including the freedom of speech, will be a fair and just verdict, a verdict that will withstand the test of history!

We earnestly request that the Beijing Municipal No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court give sufficient consideration to the opinions of the defense counsel and render a not-guilty verdict to Liu Xiaobo on the basis of the facts and in accordance with the law.

Liu Xiaobo’s Defense Counsel: Beijing Mo Shaoping Law Firm

Shang Baojun (尚宝军), Attorney at Law

Ding Xikui (丁锡奎), Attorney at Law

December 23, 2009

Translator’s Notes

1. All emphasis from source text. ^

2. Fei Xiaotong (1910–2005) is widely regarded as China’s most prominent social anthropologist. ^

3. Translation from Mao Zedong, “New-Democratic Constitutional Government,” in Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung Vol. 2 (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1967), 407–16. ^

4. Unofficial translation by Human Rights in China. ^