May 14, 2002

[English translation by Human Rights in China]

For someone who personally went through the 1989 Movement, in the long time since the June Fourth Massacre, and in the depths of my heart, the movement has not really failed. Even though it was a failure in fact, it was a failure of tragic grandeur. Compared with the temporary victory achieved with might by an authoritarian regime, the 1989 Movement holds the moral advantage over time, and I still firmly believe this when I criticize the movement.

But it has already been 13 years since the Massacre. Facing the lost souls of June Fourth on this 13th anniversary, and seeing the difficulties the Tiananmen Mothers have in continuing their fight because of their isolation, this sense of tragic grandeur is being eaten away by my own unwillingness to admit a defeat so disastrous. The difference between “tragic grandeur” (悲壮) and “tragic” (悲惨) is just one word, but this difference marks the spiritual erosion of Chinese society that worsens with each passing day as well as my own self-criticism that grows heavier with each passing year.

Why has the regime of the Communist Party of China, which owes a debt in blood but has not admitted wrong, not only not collapsed, but has been able to withstand world sanctions and moral condemnation? Why has it been able to survive a political crisis that lasted only briefly and continue to trample on human rights for more than a decade?

While the CPC-led reform and opening up policy in China began earlier than the social transformation of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and while the example of the 1989 Movement inspired civil resistance in other countries, why is it that, 13 years later, the pace of China’s political transformation lags so far behind that in those states, so much so that it is behind even the notorious Burmese military junta?

Why is it that, to-date, China’s civil opposition, having received both the attention and support of the international community, has not been able to form an organized civil pressure group? And why is it that the international community’s moral support and material assistance to China’s civil opposition forces have not achieved the results as in other countries going through transformation? And instead, the CPC regime has successfully bid for hosting the Olympics and entering the WTO?

Having gone through a civil opposition movement that shocked the world, why is it that no one from China has received the Nobel Peace Prize, the most influential among the Nobel Prizes? What is the matter with the Chinese people?

Every fellow countryman who personally experienced the 1989 Movement and still holds firm the concepts of freedom and democracy has no choice but to face this harsh truth: No one could have imagined that the 1989 Movement—which ended in its protest of the tragic and grand sacrifices in the Massacre, but which shaped a large-scale popular mobilization of mutual support across social strata, and which for the first time, made the world look upon the righteous strength of the Chinese people with admiration—could, after 13 years, have its influence worn down to nearly nothing, and the moral capital it had accumulated with blood nearly entirely squandered. The CPC has successfully distorted and purged the national memory through violent repression, ideological indoctrination, and bribery. Of those who personally experienced the Movement and the Massacre, some are overcome with regret that it has delayed their future in the world, while some are unwilling to bring up the memories of passion and bloodshed. For the younger generations who did not personally experience 1989, the majority of them do not even know exactly what had happened in China back then. In other words, the moral fervor and social consensus that launched the 1989 Movement no longer exist in China today. The pursuit of interests has overtaken the pursuit of righteousness as a priority. The great social stratification has taken the place of a consensus for political reform across all levels of society. The polarization between the elites who benefit and the ordinary people who lose has already reached a degree of sharp opposition with regard to interests. This polarization has made the mainstream elites more inclined toward a conservative stance that prioritizes stability and the economy, and toward a government-led, top-down, authority-and-order model of lame reform, as if economic reform consisting of power marketization and crony privatization with Chinese characteristics can automatically give birth to a free society. Without the active and broad participation of the elites, it is nearly impossible to launch a bottom-up civil movement for political reform.

I do not wish to replay old tunes of how the CPC is too formidable or of China’s economic success or of the low quality of the Chinese people. Rather, I will attempt to examine the civil opposition movement itself, in particular, the conduct of the elite of the opposition movement including myself. I also sincerely hope to hear voices from different standpoints.

The latest event that has provoked me to make the painful reflection below is the breakthrough change in Burma’s political situation.

In August 1988, a rally erupted in a square in Yangon protesting the military junta dictatorship and demanding freedom, democracy, and human rights. Aung San Suu Kyi delivered a famous speech at the 500,000-strong gathering, establishing her position as a civilian political leader for the Burmese people. On September 27, the National League for Democracy was formed, with Aung San Suu Kyi serving as its general secretary. The NLD strengthened rapidly under her leadership and, in less than a year, developed into Burma’s largest opposition party and actively prepared to take part in the national elections. On July 20, 1989, the military junta, fearing the loss of power, placed Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest for “inciting riots.” The democracy movement was thus suppressed by the military junta.

During the same period, like in Burma, a national civil opposition movement also emerged in China. At the height of the movement, the scale of its participation far surpassed that in Burma. Similarly, the harshness of the political environment and the barbarity of the regime in China also surpassed those of the Burmese military junta, and the severity of civilian sacrifices was unmatched by that in Burma. Also because of these differences, the respective influence of these two movements more than a decade later, and their final outcomes today, are also totally incomparable.

In Burma, the power of the military junta did not intimidate the civil opposition; rather, it stirred up their will to fight. The NLD won a huge victory in the May 1990 general election, taking 392 of the 495 contested seats in Parliament, turning itself from opposition party to ruling party in one fell swoop. But the military junta repudiated the legitimate election results by force, depriving Aung San Suu Kyi and thousands in the opposition party of their personal freedom. Whereas in China, the massacre, mass arrests, and subsequent tight inspection of everyone who crossed the border, plunged the entire country into a dead silence, so much that even the innocents who had died at the gunpoint of the martial law troops and under the caterpillars of their tanks could not be mourned publically.

But after more than a decade, Burma’s civil opposition party has not self-destructed, but has sustained its nonviolent resistance. Aung San Suu Kyi was determined to endure her loss of freedom rather than go into exile, and through various efforts, she sent out her forceful voice of resistance. Inspired by her noble and fearless character, the NLD held its resistance. One could say that the Burma’s civil opposition seemed to have maintained its resistance with a spirit that did not fear filling the prisons of the military junta. It is this dauntless tenacity that has provided ample moral and organizational resources for the development of the opposition itself and for the support of the international community. In 1991, Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. And the government which deprived a Nobel Peace Prize laureate of her personal freedom was unable to endure the intense moral pressure resulting from its actions. On May 6, 2002, Aung San Suu Kyi and the opposition party she led finally ushered in the dawn of social reconciliation. Due to Burma’s domestic situation and the formidable pressure from the international community, the military junta had no choice but to grant the unconditional release of Aung San Suu Kyi and more than 700 political prisoners soon afterwards. The junta also pledged that it would first form a transitional government with the NLD for three to five years during which the government would draft a new constitution. The national elections in 2005-2007 would complete the peaceful transformation of the political system.

But in China, though the massacre turned many liberals “within the system” into dissidents outside the system, and though the civil opposition’s sporadic challenges to the CPC regime have never ceased, but because of the of lack of a symbolic leader like Aung San Suu Kyi or a mature civil opposition organization like the NLD, and because of the exile of a great number of the key actors of the 1989 Movement, the civil opposition movement lacks a cohesive moral core and naturally is far from being organized or capable in mobilizing the masses. The opposition can only exist in a state of fragmentation and isolation, becoming increasingly marginalized. Over the past two years, public opinion and attention both at home and abroad have increasingly focused on the CPC’s generational changing of the guard. Now, as the convening of the 16th Party Congress approaches, foreign media’s discussion of the China question is inevitably focused on the transfer of power at the 16th Party Congress in an endless stream of predictions of all kinds. Many of the liberal intellectuals and democracy activists living abroad are also doing the same thing with gusto. [Vice President] Hu Jintao’s (胡锦涛) solo visit to the United States [in May 2002] drove this attention to a small climax. In China, whenever the elite who follow current affairs get together to chat, they spend most of their time talking about the power transition during the Party Congress. People spread all kinds of gossip about high-ranking officials and are especially enthusiastic in speculating on the new personnel line-up to be unveiled during the Party Congress and the political leanings of the Fourth-Generation leaders. Everyone hopes that [current President] Jiang Zemin (江泽民) will set a precedent of abolishing lifelong-tenure in the CPC retirement system, that [Vice President] Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao (温家宝) would form the core of the Fourth Generation leadership, that Li Ruihuan (李瑞环)1 would assume the chairmanship of the Standing Committee of the NPC and retain his position on the Politburo Standing Committee because of his seniority, and that the new rulers, with their new authority, can break the political ice.

In other words, Burma, our close neighbor under the rule of a military junta, has a civil opposition party which has sustained its fight for more than ten years, and has in the end taken a key step toward social reconciliation and democratic reform. While Aung San Suu Kyi’s unconditional release became the focus of the world’s attention, Chinese elites’ attention remains trained on the power transition at the 16th Party Congress. People are pinning their hopes for political reform on the possibility that the Fourth Generation leaders would be different from their predecessors, for the emergence of a Mikhail Gorbachev or a Chiang Ching-kuo from among them. With the existence of the civil opposition basically excluded from attention, no one harbors any hopes that a Václav Havel, Lech Wałęsa, Boris Yeltsin, Kim Dae-jung, or Aung San Suu Kyi would emerge in China.

Moreover, domestic liberals have made conscious effort to keep a low profile during what is known as the sensitive period of a political year. Well-meaning friends also advised that I be low-key for a while, to avoid angering the CPC and paying an unnecessary price. Before the completion of the power transition during 16th Party Congress, people seem to have nothing to do except waiting anxiously in endless speculation. Awaiting the arrival of a new savior has become an ingrained character flaw among our fellow countrymen. For the Chinese civil political opposition, such a sharp contrast highlights this grim and sad fact: a poverty of Chinese liberalism, in particular, of the democracy movement aimed to put liberalism into practice. This poverty is not of quantity but quality. In terms of quantity, we do not lag behind other transitioning countries: we have a celebrated liberal faction within the Party, dissidents known across the world, a group of young student leaders who were raised by the 1989 Movement, and men of steel who have sat in the authoritarian prisons for nearly 20 years. However, the likes of Wei Jingsheng (魏京生) from the early period2; then Fang Lizhi (方励之)3; Wang Dan (王丹),4 Wang Juntao (王军涛),5 and Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳)6 who were forged by the 1989 Movement, and Hu Ping (胡平),7 who joined the Democracy Movement from abroad in the mid to late 1980s, etc.—I do not need to list more names—if only they had coalesced into an open civil opposition, then surely China's political situation would not have come to a standstill like today’s, nor would the mainstream international community be disappointed in the Chinese democracy movement. When the Chinese people themselves are unable to form sufficient civil pressure against the authoritarian regime, pressure from the international community will also be unable to achieve its desired effect.

If one counts the April Fifth Tiananmen Movement in 1976,8 China’s civil opposition movement has continued for 26 years, with the 1989 Movement that stunned the world occurring at midpoint. But after enduring for a quarter of a century, the mass mobilization that was once glorious, and the spirit of sacrifice that was once stirring have not only failed to come to fruition, but have become increasingly impoverished morally, organizationally, and ideologically. This state of organizational poverty, be it at home or abroad among the exiles, has become ever more ashen with the passage of time.

The Chinese people are good at forming secret cliques for private gains, and the celebrated people tend to fight their own battles alone and vent their dissatisfaction about current affairs and launch their attacks privately. But it is difficult for them to form open public opposition organizations based on the needs of public good. It is not that the civil opposition has never had the opportunity to do so—but that the opportunities on many occasions to organize have all been squandered.

The first time was in the late 1970s and early 1980s. There were many citizen publications during the Xidan Democracy Wall era, and in 1980, some of the people who ran these publications were involved in campaigning for people’s congress representatives at many of Beijing’s colleges and universities. Some of them managed to get elected. If the people active in civil society at that time had the right idea and proper operations, if the noted rehabilitated public figures who were at the peak of their prestige had at the time given their support to the civil opposition, it was entirely possible for them to unite in a sizable civil society organization.

The second opportunity was during the two movements of ideological purge: the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign [1983] and the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization Campaign [1986]. In particular, the latter forced many well-known public figures within the system to a position of revolt. General Secretary Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦)9 was forced to resign, and Fang Lizhi (方励之), Liu Binyan (刘宾雁),10 and Wang Ruowang (王若望)11 were publically expelled from the Party. These men were already made folk heroes both in China and abroad by the CPC regime. It was entirely possible for them to unite other purged noted figures and other liberals to establish a civil opposition organization that was moderate and independent from the ruling party. Unfortunately, even under the pressure of forced resignation or expulsion from the Party, they still harbored hopes for the ruling party. While they were driven out and helpless, they were unable to take the next step—rebel.

The third time was during the 1989 Movement, which would have provided the best opportunity for the civil opposition movement to organize itself. Many civil society organizations were also set up during the movement. Among them were the Independent Federation of Chinese Students and Scholars, Beijing Federation of Intellectuals, and Beijing Joint Committee from All Walks of Life to Protect the Constitution had the greatest influence. Unfortunately, 1) these organizations lacked people of authority who could live up to public expectations; 2) they lacked consultation and cooperation among them; and 3) the leading figures of these organizations fled abroad fearing a violent crackdown. For these reasons, the civil opposition movement lost its best opportunity to organize. At that time, Fang Lizhi, the folk hero people looked up to most, deliberately avoided direct involvement with the movement. In the end, he fled to the United States. This caused the abundant moral capital and the authority among the people that he had accumulated to lie idle, and he missed a golden opportunity to serve as the moral symbol, spiritual leader, and cohesive center of the civil opposition.

Aside from these three lost golden opportunities, Chen Ziming (陈子明)12 and Wang Juntao (王军涛). After participating in the April Fifth Movement, the Democracy Wall Movement, and the university elections, began to consciously make an effort to organize among the intellectual elites. The research institute they established [Beijing Social and Economic Institute] was actually an embryonic civil opposition organization in disguise. By the end of the 1980s, their non-governmental research institute had made considerable stride in terms of both financial resources and scope, and it became the key organizer in the latter stages of the 1989 Movement. However, because Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao did not have enough social prestige and the great majority of the public figures who joined the Joint Committee to Protect the Constitution did not continue their support, the influence of this civil society organization was limited to the young and middle-aged intellectual elite and did not extend to society as a whole.

After that, in mainland China, the civil opposition made several attempts to organize, most famously with the formation of the China Democracy Party in 1998. But the most opportune time for organized civil forces to exist and grow had been lost. News blackout and the indifference of society as a whole enabled the CPC to successfully carry out suppressive tactics that nipped any organized civil forces in the bud.

Outside of China, although the overseas democracy movement has made several organizational attempts to reintegrate, beginning with the Chinese Alliance for Democracy in the mid-1980s, it has up to now been unable to reach a consensus on the most fundamental set of moral principles or common interests. This is because of the lack of a unanimously-chosen central figure and the lack of moral integrity and a sense of common interests. Thus, the state of intrigues against each other, standing separately on individual moral high grounds, and disunity has not really changed. This situation has fragmented the already-limited capital into pieces, and made it basically impossible for the movement to be taken seriously by the international community. Even more so, the overseas democracy movement is unable to constitute substantial pressure against the CPC regime or provide strong support for the domestic civil opposition movement. The celebrated exiles, on whom great hopes were pinned, began to lose their radiance after a brief period of fame. In the end, they too became a pack with no leader.

For every country that undergoes a successful transformation from a dictatorship to a democracy, there is a continuous accumulation of not just organizational resources but also ideological resources. It is in the complementarity of these two kinds of resources that a civil opposition takes shape. One of the reasons for the lack of progress in the political transformation of Chinese society is a poverty of ideological resources that is far greater than that in other transitioning countries, and which did not continue to accumulate. For example, each country in the former Eastern Bloc was deeply influenced by Western Europe’s tradition of liberalism, which never stopped being disseminated through theory, literature, and the arts. Further, due to the ideological thaw in the 1950s, the intellectual elite of the Eastern Bloc created a great quantity of anti-totalitarian literature, contributing commonly-used nouns to world politics. The ideological heft of The Gulag Archipelago13 surpassed the sum of all Chinese writings exposing the evils of totalitarianism. The word “gulag” was regarded as synonymous with the evils of a communist totalitarian system. The weight of its meaning is equal to that of “Auschwitz” as a synonym for genocide. There was also the spiritual depth of Václav Havel’s open letter to the General Secretary of Czechoslovakia14 which surpassed all manifestos written by Chinese dissidents.

Similarly, in Burma, Aung San Suu Kyi integrated the two spiritual resources that held universal value. One is the supremacy of human rights which originated in Western liberalism. The other is love, benevolence, and non-violence, which originated in Eastern Buddhist beliefs. While under house arrest, she wrote “Justice Needs Forgiveness to Mitigate,” a text of perfect union of these two kinds of universal values. No figure in China’s civil opposition has yet to write so nobly: “Even though I was very restricted, I had ways to keep my spirit alive. My hut within the prison compound was completely encircled with barbed wire. I was indoors all the time. And the wire was a constant reminder of how precious my freedom was. Like in the Buddha’s teachings, obstacles can be seen as advantages; the loss of one’s freedom can inspire reflection on the preciousness of freedom.”15 Just as the Nobel Committee stated on awarding her the Nobel Peace Prize: “[I]n Asia in recent decades, [Aung San Suu Kyi] has become an important symbol in the struggle against oppression.”16

In China, there were many liberal voices during the Hundred Flowers Campaign at the end of the 1950s. The writings and views of Chu Anping (储安平)17 and Lin Zhao (林昭)18 represented the strongest voices of the liberal intellectuals who protested the idea of “the Party is above all.” During the Cultural Revolution, there were Yu Luoke (遇罗克)19 and the more profound Gu Zhun (顾准),20 as well as Li Yizhe (李一哲),21 whose big-character posters called for the establishment of a legal system. But these voices all vanished without a trace in the brutal crackdown of the period. Even more, these valuable ideological resources did not become a part of the movement [in the late 1970s] to emancipate the mind and seek truth from facts or of the 1989 Movement. It was not until the mid-1990s that the ideological resources of Lin Zhao, Yu Luoke, and Gu Zhun’s and the legacies of their integrity were rediscovered.

Entering the reform era, prior to 1989, part of Deng Xiaoping’s Emancipation of the Mind campaign formed the mainstream voice of the intelligentsia’s ideological enlightenment movement. This was focused on discussions of the standards of truth and on re-interpreting Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought. But in fact it was a cry by the reformists within the Party who opposed the ossified Whatever Faction22 and were vying for ideological dominance. Of the marginalized voices, first, there were the private publications of the Democracy Wall era and their intensely anti-authoritarian writings. Wei Jingsheng’s (魏京生) appeal for a Fifth Modernization is representative of these writings. And in terms of liberal ideological depth, Hu Ping’s passionate writings on freedom are exemplary. These writings, however, were ignored by the mainstream intelligentsia and did not achieve their due influence.

Then, in the literary and art world, there were the exhibitionist misty poetry, the scar literature meant to settle scores from the Cultural Revolution, avant-garde novels, plays, films, paintings, and rock-and-roll. Scar literature was predominately intellectuals’ venting of grievances and self-embellishment; actual critical revelations of the root causes of the Cultural Revolution were practically non-existent. The youthful and rebellious misty poetry and avant-garde films influenced the esthetic trends of the generation. But, as the well-known figures in this community emerged from the underground to the mainstream, the civil society tone of their work became increasingly weak. They eventually became sources of paychecks for Western sinologists and the negative adornment for the official Writers Association, and, in the end, part of the roots-seeking cultural movement.

In the ideological sphere, there were discussions on humanism, alienation, and subjectivism along with an intense and flourishing debate on culture. The discussions of humanism proper continued on the basis of the ideological legitimacy of Marxism, using Marxian humanism to break through the forbidden zone set up by class theory, and using the revelation of actual human alienation to critique the existing system. The philosophy of subjectivism was a strange amalgam of Marxian historical materialism, Kantian subjectivism, and the Eastern theory of harmony between men and nature, dragging the heavy tail of productive force determinism, social sectionalism, and collective subjectivism. Literary subjectivism interpreted artistic creations through the lens of philosophical subjectivism, and was a hodgepodge of Kantian aesthetics, humanism, Freud, and existentialism. And the artificially cobbled together theory of moral dualism was merely a new stereotype replacing the old “larger-than-life” [高大全 gao-da-quan, literally: tall, big, well rounded] model from the Cultural Revolution era. The great debate about culture was chiefly between the neo-Confucians and the Westernization School. The former drew from a creative transformation of traditional culture to criticize the new tradition of the CPC, while harboring a kind of cultural arrogance that Eastern culture would save the world. The Westernization School had liberalism as its chief ideological resource and used the repudiation of traditional culture and the trumpeting of Westernization to criticize the existing autocracy. But the understanding of Western culture among those in the Westernization School seemed simplistic. They did not differentiate between the various factions of Western liberalism and their corresponding institutions. And the open discussion of practicable political reform only truly emerged following the aborted Anti-Liberalization movement.

But the ideological enlightenment which was ardently concerned with the actual situation at the time was deeply flawed because of the combination of the following deep institutional limitations and spiritual afflictions. 1. Reform and Opening Up again won the ruling party the support of popular will. 2. After rehabilitation, intellectuals suffer from a complex of allegiance to those who rehabilitated them. 3. Domestic resources and ideology preparation were sorely inadequate. 4. There was a restless attitude among people as they chased after quick success. 5. The dazzling view of the West left people uncertain as to what to do. 6. People used superficial national pride to conceal a sense of humiliation and inferiority. 7. Indiscriminate imitation replaced innovation through careful deliberation; 8. There was no sincere individual soul searching or remorse. 9. The environment for speech did not permit speaking the truth. . . . [Ellipses in original.] The criticism of the Mao Zedong era was mostly confined to denying responsibility and self-aggrandizement through bragging about how much one had suffered. Rarely was there any deep introspection of one’s own responsibilities. The rhetoric preaching liberalism was trapped in vacillation, shallowness, and vagueness. Passion was overabundant but thinking was insufficient; there was too much skirting the issue but not enough straight talk. The neo-Confucians, devoted to the creative transformation of traditions, were unable to smoothly connect traditional values and modern liberalism. They simply were not able to forge modern political ideals from traditional moral values, and inadvertently became a cultural footnote and a theoretical excuse for official patriotism. The Westernization School, embracing the Western Zeitgeist against traditional values, had a too general and superficial understanding of liberalism, and was unable to find a way of articulating it that fit China’s national conditions. The state of the cultural and intellectual circles at that time was this: The ideological environment in which the torchbearers had been raised was a cultural desert completely devastated by the struggle philosophy and linguistic violence [of the Cultural Revolution]. The torchbearers themselves thus first needed to be enlightened. How could an enlightenment movement that was at once deeply critical and constructively visionary be launched in a great transformative era that urgently needed extensive and profound ideological enlightenment? At a time when common sense about robust institutions and about treating others with compassion was far from being formed among the elites, how could such common sense be spread to the general public?

Thus, beginning in the mid-1980s, people filled the spiritual void left behind by the collapse of faith in communism not with the revisionist CPC ideology or the humanism, neo-Confucianism, or Westernization School of the intelligentsia, but with the qigong craze, the martial arts [adventure novels] craze, and the Chiung Yao [romance novels] craze. These were all contemporary vehicles for traditional Chinese culture and coincided with the roots-seeking Zeitgeist in the cultural sphere and they inflamed one another. After June Fourth, the CPC devoted its strength to opposing a Westernized and liberalized peaceful transformation and instead extolled patriotism and promoted traditional culture. This resulted in the rapid development of the large-scale civil society groups Zhong Gong23 and Falun Gong in the 1990s. At the same time, Wang Shuo’s novels, movies, and television series were wildly popular, entertaining a society under intense political pressure with satirical comedies. They provided people with relief from their crushing repressions, while mockingly subverting the CPC’s ideological legitimacy and encouraging nihilistic and nonchalant bad-boy attitudes. Unfortunately, as the Wang Shuo craze swept through the population, the sense of relief eventually dissipated while the nihilism and nonchalance became firmly entrenched tendencies among people.

In fact, whether it was the qigong craze with its elements of superstition and sorcery or the Wang Shuo craze with its subversiveness and nihilism, their rapid popularization was a normal phenomenon following the collapse of orthodox ideology. Caught in the helplessness of their sense of justice under assault and of their inability to channel their political fervor, people turned to physical fitness, promises of longevity, hedonism, and greed, in order to sort things out. From the perspective of civil society alone—setting aside the widespread corruption in government and its fatal poisoning of the society’s spirit—the intellectual elite were not qualified to denounce the Wang Shuos and the public infatuated with qigong and popular culture. It is extremely unfair for them to bear the main responsibility for the spiritual void and moral decay in Chinese society. People have their limitations, and the subversiveness of the Wang Shuos already played its part sufficiently. The primary responsibility to redress the spiritual ruins left behind by that subversiveness should have been borne by the intellectual elite. However, at a time when the intellectual elite did not provide the masses with quality spiritual sustenance either ideologically or morally, it was only inevitable that the Li Hongzhis24 and others would use their vulgar quasi-religion qigong to fill that void.

In the context of the overall spiritual atmosphere, nothing contributed more to the severity of the spiritual harm suffered by the people than the intellectual elite’s selfishness and cowardice, and their becoming part of the rich and powerful themselves in recent years as they faced the barbaric massacre perpetrated by the CPC and the unbridled plundering by the rich and powerful. This elite pushed civilians before the muzzle of the gun and fled for safe ground. They were enthusiastic in defending corruption stemming from crony privatization and the trade between money and power, but were indifferent toward the tragedies of the CPC’s repression of Falun Gong practitioners and the disadvantaged whose rights and interests were gravely damaged. Even the liberal left wing which cared about social justice and the “new Maoists” who claimed to firmly identify with the average citizen would never in fact speak up and take a stand on behalf of the persecuted. This was a conspiracy among power, money, and knowledge with Chinese characteristics. This kind of intellectual elite could only serve as the active enablers of, or passive hangers-on to, society’s spiritual degradation. It was essentially impossible for them to be a symbol of society’s conscience or a pathfinder to fill the spiritual void. So, the enormous fascination that everyday people had with the Wang Shuos and the Li Hongzhis not only attested to the failure of official ideological indoctrination, it also revealed the poverty of the intellectual elite’s ideology of enlightenment and their intellectual character. Rather than endlessly denounce society’s spiritual degeneracy, it would be better for the intellectual elite to muster the courage for self-reflection and take responsibility to rationally examine their own descent into cynicism.

To return to China in the late 1980s, the 1989 Movement began under this impoverished ideological enlightenment and shattered intellectual character. The liberal intellectuals did not display any ideological appeal that they ought to have. And they lacked even more the capacity and courage to transform their ideology of enlightenment into real action. With their dynamic actions, the college students and citizens who participated in the 1989 Movement left a rich moral legacy. But the intellectual elite who joined the Movement left no trace of an ideological legacy in which one could take pride. If the intellectual elite who personally experienced this great movement were to look back on what they said at the time, anyone who reflects on this honestly would turn red with shame. A comparison between the ideological resources the intellectual elite provided for the Movement and the moral fervor, scale of mobilization, and peaceful and rational nature of the Movement would find them greatly out of proportion. The immense contrast between the two could even be described as a contrast between the insignificant and the monumental.

Without an active and sustained civil resistance, an evil system will not collapse voluntarily even when it is rotting away in the people’s soul. To change the silent majority’s state of indifferent, cowardly, and ignorant existence, the intellectual elite must first dare to break their own silence and show a conscience that is no longer indifferent, a courage that is no longer cowardly, and a wisdom that is no longer ignorant. After more than a decade of the complete bankruptcy of the CPC’s totalitarian regime, China’s one-party authoritarian system remains stable. A key reason is the insufficiency of civil society forces, in particular, the poverty of conscience and courage among the civil society elite.

Something very ironic is that after the June Fourth massacre, the most typical theory that defended this kind of moral poverty actually came from the pens of the liberal intellectuals. These intellectuals completely ignored the current reality of the ever-present political terror created by a powerful autocratic regime. They also completely overlooked the fundamental difference between the meaning of “conservatism” in a West that has a tradition of liberalism, and that in a China that had never had that tradition, and that this conservatism could not be directed laterally transplanted. But they insisted on using the Anglo-American negative liberty or conservatism as a starting point, and erroneously analyzed and criticized the failure and mistakes of the 1989 Movement as a typical example of French active liberty. They deduced from the concept of negative liberty a rational basis for political apathy evident in phrases such as “the right to be absent from history,” “leave reality and return to the study,” and “don’t talk about national affairs.” It was in this refuge of negative liberty with Chinese characteristics that the elite found their stately reasons for refusing to face the harsh reality of autocracy. As a result, this theory does not only lack forceful criticism of the actual reality of China, but also turned the Anglo-American liberal tradition of the West pale and cynical under the pens of China’s liberals.

History has made clear that, without exception, in every autocratic country that has completed the peaceful transformation of its social institutions, a continuous civil opposition movement exists. The success or failure of civil opposition movements depends to a great extent on the actions of the civil society elite. A mature civil opposition movement must bring forth symbolic figure who can rally popular opinion, inspire courage, and enlighten the masses. This person often has a considerable reputation prior to joining the civil opposition movement. Once this figure has resolved to break with the autocratic system, his or her prior reputation will be transformed into a tremendous force for cohesion and appeal in society. They are the embodiment of moral courage, the well-spring of ideology among the people, and the core of organization for civil society. In the Soviet Union’s transformation, the early moral symbols were the dissidents Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn. The former was the father of the missile, the latter a laureate of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Following them were Gorbachev with his top-down political reforms. Then it was Yeltsin, who resigned from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union to stand with the people, and became a leader who promoted the transformation of the Soviet Union from the bottom up. He showed political daring and moral courage at a critical point in history, and became a symbol of popular will on which the people pinned their hopes. The transformation of the Eastern European countries was made possible by, first, the Soviet Union relinquishing its military intervention in Eastern Europe, and, second, the sustained increase of pressure from the people. Popular pressure groups continued to expand largely due to the moral heroes who stood firm in the face of politics of terror. Poland had Solidarity led by Lech Wałęsa, and Czechoslovakia had its dissident movement with Václav Havel as its symbolic figure. In Asia, there was Kim Dae-jung of South Korea,25 who almost lost his life in resisting a military junta. South Africa had Nelson Mandela,26 who was imprisoned for 29 years. The Philippines had Benigno Aquino, Jr.,27 who gave his life for his cause. And Burma, now only at the dawn of political reconciliation, has Aung San Suu Kyi, who would rather be un-free than exiled. She once made a speech surrounded by heavily-armed soldiers during which she told them calmly, “I wish to thank you all. It is you all who made the people show their courage.” These moral heroes played the key role of being the enduring strength that cohered and mobilized the civil opposition forces and enabled the valor, wisdom, and perseverance in resisting tyranny to become mutual encouragement between the people and their leaders.

By contrast, in China, a series of civil opposition movements and suppressions by the CPC regime had once provided opportunities for a number of moral heroes who attracted attention worldwide. Unfortunately, they—because of either their lack of moral courage or their arrogance and small-mindedness—found it difficult ultimately to bear the heavy responsibility of being the cohesive core and moral symbol of the people. If the celebrated figures of the Democracy Wall era were better known abroad than at home, and could not make people identify with them, then, Fang Lizhi, Liu Binyan (刘宾雁), and Wang Ruowang (王若望)—who came to the fore during the Anti-Spiritual Pollution and the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalization campaigns [in the 1980s]—were recognized both at home and abroad as the heroes of the people at the time. The 1989 Movement further focused the eyes of the world on Beijing, and created a number of celebrated figures well-known in China and the world: the world-renowned student leaders, and the celebrated intellectuals and private entrepreneurs. Influential members of the Party’s liberal faction also stepped into the limelight, including Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳), Bao Tong (鲍彤),28 Xu Jiatun (许家屯),29 and their aides. The exiles among them were given heroes’ welcomes overseas so much so that they became triumphant exiles. This was something seldom seen in the history of exiles and seems to be exclusively enjoyed by the Chinese exile community. The political prisoners arrested in China also received considerable attention at home and abroad.

They were fortunate in that they had the opportunity and ample capital among the people. It was not only the personal price they paid in their persecution and imprisonment but also the blood of the massacre that earned for these men of the moment this moral capital that was too abundant. The social status enjoyed by the celebrities of the 1989 Movement was achieved with the blood of the people. In China’s civil opposition movement after June Fourth, the best “what-if” scenario would have been: What if Fang Lizhi had left the American Embassy and faced trial by the CPC? What if everyone had remained [in China] to fill the CPC’s prisons? What if Zhao Ziyang had publically broken with the Party, as Boris Yeltsin had, and continued to speak out? [If these scenarios had taken place,] then the political opposition after June Fourth would have formed such an immense array of troops among the people, would have in turn received such massive domestic and international support, and the Nobel Peace Prize would also have been extremely likely bestowed on one of the opposition’s elite. This would have brought forth the people’s courage to rebel as well as constituted powerful political pressure against a regime rapidly losing its legitimacy. In other words, any prison of an autocratic system holding a Nobel Peace Prize laureate will become an evil symbol universally condemned as well as a symbol of a people’s moral courage and the core of civil opposition.

This kind of hypothesis and hope is in no way overly harsh moral censure because the moral obligation borne by the celebrated figures of the 1980 Movement should be commensurate with their prestige. Placing moral demands on these well-known figures is by no means unreasonable; it is simply common sense. (For example, extra-marital affairs are commonplace, but Bill Clinton was subjected to the reprobation of the society—legal investigation, congressional hearings, public criticism.) To say nothing of the fact that in China the personal price paid by the well-known figures of the 1989 Movement was merely imprisonment. This pales in significance when compared with the price in human lives that had been paid by the people. It is basically nothing worth flaunting or should it become their personal capital on which to rest their laurels. They have not the slightest reason to squander away this sacrifice of tears and blood. In other words, there is a huge rift of disparity between the way the well-known Chinese dissidents behave and the social responsibility they should bear that come with the prestige they enjoy. When the famous elites are unwilling to hold fast to their morals and conscience and step forward to pay a personal price in the most terrifying and critical juncture, then the masses will naturally have no obligation to have high expectations of them or give them support. The moment when celebrities shirk their obligations to society is when the masses withdraw all social honors they have bestowed on them. When Falun Gong practitioners in mainland China defy the powerful and lose their personal freedom—sometimes losing their lives—for their beliefs, they have the right and are entitled to demand that the head of their religion step forward, and the society also has the right to morally condemn Li Hongzhi who remains on the other side of the Pacific. It was not the ignorance of the silent majority but the cowardice and lack of responsibility of the elite few that allowed the CPC regime to safely weather the crisis of legitimacy after the massacre. One of the chief reasons for the success of Burma’s civil opposition and the failure of China’s civil opposition is the world of difference between the elites who lead the respective movements: an Aung San Suu Kyi who is of greater consequence than a dozen Chinese dissidents.

After June Fourth, the CPC regime’s secure survival of the political crisis and the moral decay of society as a whole, the isolation of the few rebels and the buying off of the majority of the elites, the thickness of people’s wallets and depth of spiritual cynicism, the CPC’s checkbook diplomacy and the international community’s tradeoff between moral priorities and interest priorities—all helped maintain the stability of a CPC dictatorship that owes a blood debt to its people.

Along with this is the increasing moral, ideological, and organizational impoverishment of the civil opposition. The increasing isolation and marginalization of the civil opposition movement made it impossible to form broad mobilization across all social strata in solidarity and lasting commitment. Each group's opposition to tyranny is limited to the vested interests of that group; and the selfish focus on only one's own problems has become the ethic norm in China today. Whether it is the petitions of dissidents, resistance by families of the victims [of June Fourth], demonstrations by the disadvantaged groups, or the martyrdom of Falun Gong practitioners—nearly all forms of civil resistance are isolated and cannot constitute a genuine civil society challenge to the authoritarian regime. The most typical cases are the families of the victims [of June Fourth], represented by Ding Zilin (丁子霖) [of the Tiananmen Mothers], the Falun Gong practitioners’ defense of Falun Dafa, and the protests by disadvantaged groups. The [Tiananmen] Mothers’ moral courage in their resistance against tyranny is nothing short of moving, and the results of their humanitarian relief are nothing less than outstanding. The tenacity and martyrdom of Falun Gong practitioners are nothing short of tragic. The masses who have suffered losses have abundant reasons for protesting. And yet, these three groups can only stand isolated in the coldness of indifference, unable to gain broad support from the elite.

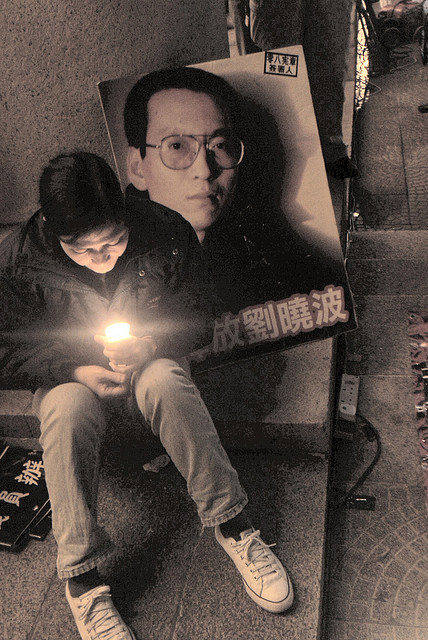

Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波), 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, is an independent intellectual in China, and a drafter of Charter 08, an appeal for political reform in China. He is a long-time advocate of political reform and human rights in China and an outspoken critic of the Chinese Communist regime. Liu participated in the 1989 Democracy Movement and was found guilty of “counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement” in 1991 but was exempt from punishment. In 1996-1999, he served three years of Reeducation-Through-Labor for “disturbing social order.” Liu was detained on December 8, 2008, two days before the release of Charter 08. On December 23, 2009, he was convicted of “inciting subversion of state power” and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He is serving his sentence in Jinzhou Prison in Liaoning Province.

Translator's Notes

1.Li Ruihuan (李瑞环) was a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo of the CPC during 1989-2002. Before the 16th Party Congress, Jiang Zemin, then General Secretary of CPC, introduced a new policy, called “seven up and eight down,” which required members of the Standing Committee to be 67 or younger—and not those 68 or older—when elected. This policy was widely viewed as a tactic to prevent Li Ruihuan, then 68, a liberal within the Party, from being re-elected as a member of the Standing Committee.^

2.Wei Jingsheng (魏京生) is best known for his essay “The Fifth Moderation” during the Democracy Wall movement; he was sentenced to 15 years in prison for his involvement in the movement. After his release in 1993, Wei was again sentenced in 1994 to 14 years in prison. He was released in 1997 and sent into exile in the United States.^

3. Fang Lizhi (方励之) was a prominent astrophysicist accused of being a key instigator of the 1989 democracy movement. He went into exile in the U.S. in 1990 and died in 2012.^

4. Wang Dan (王丹) was one of the student leaders during the 1989 democracy movement. He was sentenced to four years in prison in 1991, released from prison in 1993, arrested again in 1995 for, and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He was released early and sent into exile in the U.S. and currently teaches in Taiwan.^

5. Wang Juntao (王军涛) founded the Beijing Social and Economic Sciences Research Institute with Chen Ziming in 1985. He was arrested in Guangdong after June Fourth and was sentenced to 13 years in prison in 1990. In 1994, he was released to go to the U.S. for medical treatment and then unable to return.^

6. Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳) was the People’s Republic of China’s third Premier until he was purged for being sympathetic to the protesters of the 1989 Democracy Movement. He remained under de facto house arrest until his death in 2005.^

7. Hu Ping (胡平) was an activist in the Democracy Wall movement in 1979 and former president of Chinese Alliance for Democracy. He has been based in the U.S. since 1986, where he currently edits Beijing Spring. He is a board member of Human Rights in China and Special Contributing Editor to its publications.^

8. The Tiananmen Incident occurred in Beijing on April 5, 1976 (Qingming Festival), when tens of thousands of people protested the removal of wreathes and flowers placed the day before to mourn Premier Zhou Enlai, who had died the year before.^

9. Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) was an outspoken liberal politician who at his height served as Party Chairman and then Party General Secretary to the Communist Party of China under Deng Xiaoping. Hu was forced to resign as General Secretary after refusing to dismiss Fang Lizhi, Liu Binyan, and Wang Ruowang from the CPC following student protests for economic and political freedoms in 1986-7, and for his push for liberal economy policies. He was replaced by Zhao Ziyang.^

10. Liu Binyan (刘宾雁) was a journalist and dissident. A member of the Communist Party, he was first expelled from the CPC during the Hundred Flowers Campaign in 1957, rehabilitated, and re-admitted to the party in 1978; in 1987, Liu, Fang Lizhi, and Wang Ruowang were implicated as spearheading student protests for economic and political freedoms and expelled from the party. He went into exile in the U.S. in 1988.^

11. Wang Ruowang (王若望) was an author and dissident. A member of the Communist Party, he was first expelled from the CPC in 1957, and then re-admitted to the party in 1979; in 1987, Wang, Fang Lizhi, and Liu Binyan were implicated as spearheading student protests for economic and political freedoms and expelled from the party. He went into exile in the U.S. in 1992.^

12. Chen Ziming (陈子明) is an economist and journalist who founded the Beijing Social and Economic Sciences Research Institute with Wang Juntao in 1985. He was arrested in Guangdong after June Fourth and was sentenced to 13 years in prison in 1990. In 2004, he helped set up a website called Reform and Construction, but the site was shut down by authorities in August 2005.^

13. The Gulag Archipelago, by Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and published in 1973, chronicles the USSR’s forced labor camps (gulag), including both history and eye-witness accounts.^

14. In April 1975, Czechoslovakian writer and dissident Václav Havel wrote an open letter to the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in which he argues for “elevation of man to a higher degree of dignity, for his truly free and authentic assertion in this world.” It was his first public statement after being banned from the theater due to the 1968 Prague Spring. Václav Havel, “Dear Dr. Husák,” April 1975, http://www.vaclavhavel.cz/showtrans.php?cat=eseje&val=1_aj_eseje&typ=HTML.^

15. Although sometimes attributed to Aung San Suu Kyi, this was said by General Thura Tin Oo, deputy leader of the National League for Democracy. Tin Oo, interview with Alan Clements, Aung San Suu Kyi, The Voice of Hope (New York: Seven Stories Press, 1997), 217-8.^

16. Norwegian Nobel Committee, “The Nobel Peace Prize 1991,” October 14, 1991, http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1991/press.^

17. Chu Anping (储安平) was a journalist who edited the Guangming Daily (光明日报) after it began operating directly under the CPC Propaganda Department. Chu was labeled a rightist during the Anti-rightist Movement in 1958, and went missing at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966.^

18. Lin Zhao (林昭) was a dissident who participated in the Hundred Flowers Campaign in 1957 and sentenced to 20 years in prison for her involvement before being executed in 1968.^

19. Yu Luoke (遇罗克) was a young intellectual executed for speaking out against the discrimination of people based on their family’s lineage. Yu wrote several essays attacking lineage-based discrimination, one of which, “Theory of Class Origin” (出身论), he printed as a book and circulated himself. He was arrested in 1968 after his book was denounced by the Central Cultural Revolution Group, and executed in 1970.^

20. Gu Zhun (顾准) was an economist who promoted market reforms under socialism during the Mao era. He was labeled a rightist in 1957 after publishing his article “On Commercial Production and Theory of Value under Socialism” (试论社会主义制度下商品生产和价值规律) and again in 1964.^

21. Li Yizhe (李一哲) was a pseudonym derived from three major members of an underground dissident reading movement—Li Zhengtian (李正天), Chen Yiyang (陈一阳), and Wang Xizhe (王希哲)—who posted a well-known big-character poster in Guangzhou in 1974. The poster, “On Socialist Democracy and the Chinese Legal System” (关于社会主义的民主与法制), attacked the Mao rule obliquely, criticizing the “fascist” rule of the “Lin Biao system.”^

22. The Whatever Faction (凡是派) was a group of supporters of Hua Guofeng (华国锋), Mao Zedong’s chosen successor. They take their name from the statement, “We will resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made, and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave.”^

23. Zhong Gong (中功), short for Chinese Health and Wisdom Enhancement Practice (中华养生益智功, Zhonghua yangsheng yizhi gong), is a qiqong movement organized by democracy activist Zhang Hongbao (张宏堡). It was declared a cult and banned in 1999, along with Falun Gong.^

24. Li Hongzhi (李洪志) is the founder and leader of Falun Gong.^

25. Kim Dae-jung was a politician, activist, President of the Republic of Korea (1998-2003), and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. A vocal leader of South Korea’s opposition under military dictatorship, he was arrested and placed under house arrest or in prison several times. As president, Kim advocated engagement with North Korea and the elimination of the death penalty.^

26. Nelson Mandela is a politician, activist, the first president of post-apartheid South Africa (1998-1999), and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. After years of non-violent protests against apartheid, Mandela co-founded Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), an armed resistant wing of the African National Congress (ANC). He was convicted first in 1962 and again in 1964 and sentenced to life. In prison, Mandela increasingly became a worldwide symbol of the anti-apartheid movement. He served 27 years and was released in 1990.^

27. Benigno Aquino, Jr. was a Filipino politician who loudly opposed the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos and later the martial law under Marcos. Aquino was arrested in 1973, convicted in 1977, and sentenced to death. In 1980, he was released to the United States for medical treatment. He was assassinated in the airport upon his return to the Philippines in 1983.^

28. Bao Tong (鲍彤) is formerly the Policy Secretary of the late premier Zhao Ziyang and Director of the CPC Central Committee’s Office of Political Reform. He was the highest-ranking official to be sentenced to prison for opposing the use of force to suppress the 1989 Democracy Movement. Bao was arrested on May 28, 1989, and convicted of “revealing state secrets” and “counterrevolutionary propaganda” and sentenced to seven years in prison in 1992. He has remained under house arrest in Beijing.^

29. Xu Jiatun (许家屯) was formerly a member of the CPC Central Advisory Commission and head of the Xinhua News Agency in Hong Kong under British rule. He defected to the United States in 1990. Before the handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China, the Xinhua News Agency was the de facto Beijing liaison office in Hong Kong.^