Before you read this review, and, I hope, F, remember that Mao Zedong’s giant portrait still gazes down on Tiananmen Square. On the book’s jacket there is this statement by the Great Teacher: “What kind of people are those we don’t execute? We don’t execute people like Hu Feng, not because their crimes don’t deserve capital punishment but because such executions would yield no advantage. Counterrevolutionaries are trash, they are vermin, but once in your hands, you can make them perform some kind of service for the people.”

Apart from the many millions whose deaths he ordered or caused, no one suffered more or longer at Mao’s hands than Hu Feng, because—this is impossible where we live—of what he wrote. Born in 1902, Hu studied at China’s two leading universities, read literature in Japan where he joined the Communist Party and after returning to China formed a close relationship with Lu Xun, arguably China’s best writer in the 1920s and 1930s. Like Lu Xun, Hu Feng, although a Marxist, became convinced that writers should write what they felt and believed, what used to be called “subjectivity,” which brought him into conflict with Mao who, by 1942, was emphasizing that literature and art must serve the Party and aim at its enemies.

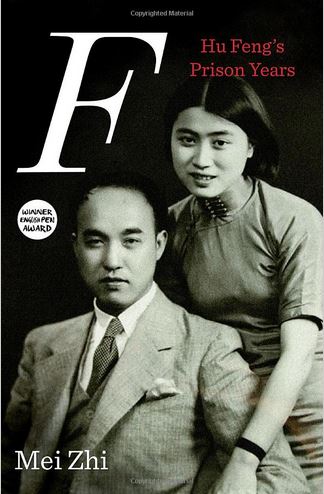

Disagreeing with Mao on any issue was always perilous, but on literature and the arts it was dicing with death. Writers like the famous Ding Ling, who had been persecuted by the Party, turned on Hu in order to save themselves. In 1955, Hu went to prison for 25 years. After Mao’s death in September 1976, like many other victims of his hatred and revenge, Hu was slowly and then, in 1979, fully rehabilitated and awarded a vacuous political position. Ill in body and mind, he died in 1985. His devoted and brave widow, Mei Zhi, who had also gone to prison, for six years, devoted the rest of her life to preserving her husband’s health and extending his life. Four years after Hu’s death she wrote this intensely sad and penetrating memoir of their final agonizing years together, most of it in horrendous exile, where Mao’s willing persecutors tormented them.

I have written the above, much of it based on the scholarship of Harvard’s Merle Goldman, because Gregor Benton, a well-regarded China specialist, author of many books, and ex-professor at Leeds University and Cardiff University, who provides the limpid translation of this poignant story, says not a word about the Hu Feng case. In fact, this book, mistitled, is about only the last miserable 20 years of Hu’s life. A reader new to Chinese affairs would wonder what Hu and his wife did to deserve such persecution.

In 1965, ten years after Hu’s arrest and imprisonment, his wife Mei Zhi, who had been freed after six years behind bars, essentially for being her husband’s wife, is permitted to visit him in prison. She had neither seen nor heard from him for ten years. Hu was in Qincheng prison, then China’s most notorious place for significant political prisoners; it was there that Mao’s widow, Jiang Qing, the key figure in the Gang of Four, Mao’s closest cronies before he died, hanged herself. Mei Zhi wonders: “Ten years without ever seeing someone dear to you. What will he be like? Will he be the man of my dreams? Will I recognize him? I don’t know how many times I imagined it, how many times I prepared my little speeches.”1 During their subsequent meetings they are closely monitored, which was to remain true for the rest of their lives, whether together or apart. “I knew this or that literary figure had climbed the ladder,” Mei Zhi recalls, “fallen into disgrace, or played up to those in power, but I also knew a single wrong word, however true, could lead to the break-up of a family [they had three children]. All these things left me terror-stricken.”2 While Hu remains in Qincheng, she is scrutinized for her involvement with her husband’s “clique,”3 a procedure “like eating sour fruit,” but already and for the next years she found herself babbling sentences like this: “I sincerely thank the Party for its magnanimity, in future I will strengthen my ideological remolding.”4

The Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976, is just around the corner and, as always in China—to this day—it was articles condemning “poisonous weeds,” essays, poems, or novels, which could mean, literally, death, for their authors or people who had previously praised them. Suddenly she was told that the Party was preparing to remove her and Hu Feng’s “hats.” When at last, the Party’s campaign to disgrace came to an end, after which, one is again a citizen, Mei Zhi “wept tears of gratitude.”5

Hu is freed, briefly, they are at home together in Beijing, they shop, they see their children, he writes groveling poems in praise of Mao, and is sometimes “lost in thought at the revolutionary commitment of the people.”6 Then banishment to Sichuan, moving to increasingly ghastly quarters, ever-tougher interrogations and abuse, and his gradual breakdown. This is what the book is about. He is still being attacked in the press for “crimes” committed in the 1940s. Hu writes longer and longer confessions; they are fantasies, arising from his deepening paranoia. In 1967 he is imprisoned again, she has no idea where. After several years of no contact, when he is released, but not pardoned, he is broken in body and spirit. Falling to his knees, he says he has committed monstrous crimes and that he has involved her in a vast mess.7

Back with her under close house arrest, Hu imagines people watching, listening, and coughing—when there is no one there. He hears his son, who is far away, being tortured. At night he knows that a new electronic device means that his watchers and interrogators are able to read his thoughts. Mei Zhi herself is near breaking point; she considers joint hanging. She manages not to: “We are living evidence—Hu Feng, for the case, and for the many friends who had been implicated. I resolved to live on, so we could emerge from those four walls alive.”8 By now, he is bleeding internally and externally and has taken to drinking his own urine.

Premier Zhou Enlai dies. They weep for this man who would cooperate with Mao on any enormity. Mao dies. They weep even more deeply. Now Hu’s keeper directs him to attack the Gang of Four—about whom he knows almost nothing—but he writes some meaningless fragments as the watch on him slowly relaxes. His paranoia drifts back and forth and his body generally deteriorates. The keepers make clear they want him alive to keep on confessing, although he frequently says, because of his physical and mental anguish, that he longs to die; they wonder if he has anything to say on the changes since Mao’s death.

Hu Feng and his wife are considering what Mao had said about executions. Mei Zhi said to her husband, “he [Mao] just said it was wrong to kill people, people’s heads were not like leeks, if you cut them off by mistake, they wouldn’t grow back . . . . I secretly poked out my tongue and F smiled wryly, ‘If you’re worried about mistakes, that means you probably made some,’”9 Soon his minders advise him that he could render “meritorious service in the struggle to expose and criticise the Gang of Four so that they could remove his hat.”10 Had Hu done just that before Mao’s death, it could have been fatal.

F is made less credible by many pages of verbatim discourse from years before, a common defect in Chinese memoirs, but the story is all-too believable, and increases one’s amazement that Mao’s portrait still hangs over Tiananmen.

F: Hu Feng’s Prison Years

Mei Zhi

Edited and Translated by Gregor Benton

Verso

Publication Date: February 12, 2013

Hardcover: 332 pages

Jonathan Mirsky (梅兆赞) is a historian and journalist specializing in Chinese affairs. In 1990, he was named British International Reporter of the Year for his coverage of the 1989 Democracy Movement in China. Until 1998, he was the East Asia editor of The Times of London.