[English translation by Human Rights in China]

“Shun! Guess where I am now?” These were the first words that burst out of my mom after her “long distance” phone call finally got through. I could hear the great excitement in her voice, but I didn’t realize she was already abroad. Besides, back then, online phone services such as Skype were just becoming popular, and I would often call my classmates to trick them into believing that I was overseas. Therefore, without thinking, I replied, “You’re in Guangzhou, for sure! These little tricks won’t fool me.” “Seriously, I’m out of China! But I don’t know exactly what country I’m in though,” my mom said with full confidence. “I’m busy with things right now. Chat later.” Like that, she hung up.

“I don’t know exactly what country.” Isn’t someone going overseas supposed to have a clear idea what country she is in? Shouldn’t a thoughtful person have all the details sorted out before traveling? Well, given my mother’s disposition for leaping before looking, that sounded like something she would do. Nevertheless, I was flummoxed.

Sitting right next to me was my father, watching TV while enjoying a cigarette and a cup of tea. “Your mom is abroad?” He asked after I hung up the phone. When I said “yes,” he took two more puffs of smoke and another sip of tea. I had thought he’d be very surprised to hear this. But he wasn’t. “So, do you want to go with her?” he asked. I was the one who was taken aback.

Many Chinese parents dream about sending their children abroad, and my parents were no exception. In fact, my dad started planning to send me abroad to study a long time ago. The first time my dad mentioned this to me was probably when I was in the fifth grade. He picked me up after school on his motorcycle and said, “Shun, Dad has a thought. How would you like it if I send you to study in Canada or Australia after you graduate?” I wasn’t sure whether it was a serious proposal or random talk, but I said “no,” immediately, without thinking. It was 2001, not long after 9/11.

The terrorist attack raised serious concerns among Chinese people over the safety in foreign countries, at least that was what the news said. Little did I know that in just a matter of a few years, my desire to go abroad would become so intense.

My dad, as it turned out, vetoed the idea after he found out where my mom was through several phone conversations with her. I wasn’t too disappointed. Granted, I wanted to go abroad and see the world. But because my mom was in Thailand, and a refugee’s status meant instability, I extinguished my desire. After all, to many Chinese, Thailand was chaotic and worse off than China economically. Thus, I decided to stay in China until a better opportunity presented itself.

In the following few months, going abroad was completely out of the picture. My dad never mentioned it again, and I didn’t give it another thought. Without much ado, I graduated from junior high, and entered to high school.

Shortly after my 17th birthday, my dad handed me a stack of paper after I came home from school and had dinner. He said in a calm tone, “These are your plane ticket and passport, and the visa was already taken care of. I had dinner and made arrangements with this friend of mine who is taking you. The flight is in four weeks. All you have to do is give your mom a call and ask her to pick you up at the airport then.” I, having completely discarded the idea of going abroad, was at a complete loss. Noticing my doubt, my dad further explained, “I don’t want this either. If you go live with your mom in Thailand, where to go to school and how to live will be two big questions. But after thinking about it over the past few months, I think letting you go abroad is the best solution. “Solution?” I asked. “Yes. Do you still remember the two times when the folks from the neighborhood office and the local police went to your school and gave you trouble?” I nodded. “That’s why I said going abroad is the best solution. When they harassed you the second time, I pulled some strings and negotiated with them. We reached a deal eventually that they would no longer come harass you before you turn 18, when you will become a legal adult. Now you are 17, and in less than a year, the underage ID card will be invalid. Besides, you can give your mom a hand, too—that woman (my parents referred to each other as “that woman/man” since their divorce) speaks no English at all. I will be tying up loose ends here.”

In February 2007, I, still a little bird not yet fully fledged in my father’s eye, flew to Thailand as he arranged, and arrived at my mom’s place.

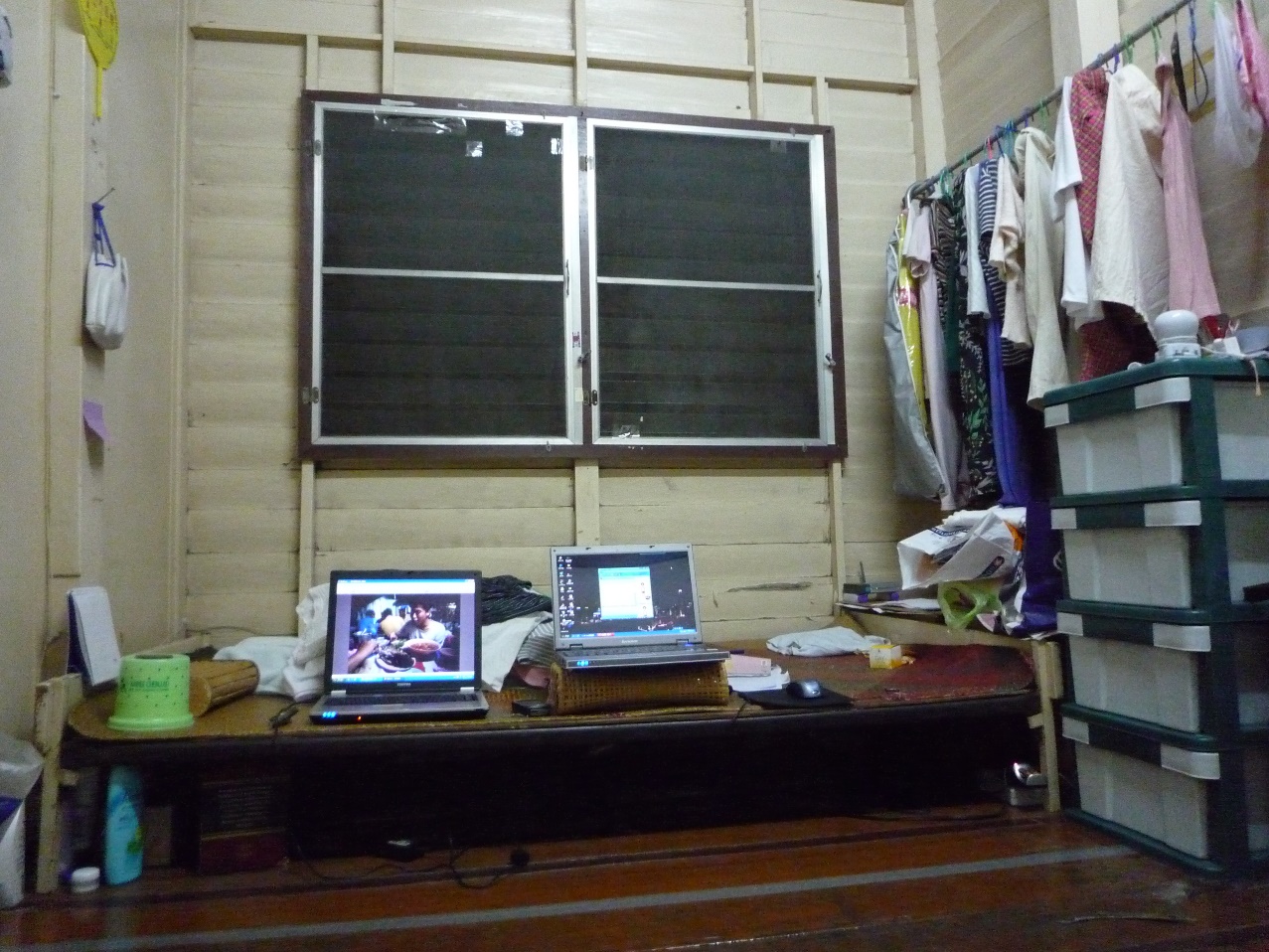

Inside our room, Bangkok, 2008.

The kind of two-story wooden house my mom was living in was very common in Thailand. On the dark and dank first floor there was a shower room and a toilet across the wooden staircase. There, the standing water and food waste clogged in the drain gave off a rancid odor. Even though the residents had a cleaning schedule, it was often not clean enough. Bugs like centipedes and earthworms were occasional visitors to the shower room and the toilet. Oh, and don’t even get me started on the cockroaches.

The dirty washing area on the first floor of our house, Bangkok, 2008.

This made me wonder how many years we should live there. What was worse, we might be stuck there our whole life if no third country would take us. I took a look at the return ticket my dad gave me before I left China, and remembered him saying, “You can use this ticket and fly back within two months if things are really bad. I will come pick you up at the airport.” I began wavering about living abroad. But I thought, I was the one who wanted to take my chances in a different country—how can I give up on Day One? Moreover, isn’t this a wonderful opportunity to toughen myself? Giving up now would just be too lame!

Just like this, on the second day in Thailand, I tore apart the ticket and threw it in the trashcan.

After I had made up my mind about staying in Thailand, my mom asked me to write an essay detailing my interactions with the local police and neighborhood authorities and stating my reason for leaving China. She said it was a required document for my refugee status application. To save time, my mom asked a friend of hers to translate my finished essay, instead of waiting for the official translation by the United Nations Refugee Agency, which would have taken a month due to the huge number of applicants.

About three days later, my mom’s friend had the translation ready, and my mom took me to the UN Refugee Agency to submit my application right away. We first took a 40-minute ride on an air-conditioned bus, more expensive than the regular ones.

We got off the bus and walked a long way. We walked past the front gate of the UN Refugee Agency, and stopped in front of a not very noticeable security door. We rang the bell, and someone answered the door. We were let in after my mother explained in her broken English that we were there to hand in application materials.

A Chinese interpreter met with us and said the interviewer would interview me that day since there weren’t many applicants.

The interview was not as hard as we’d thought. The officer only checked and verified my information and asked for times and dates of events on the application materials. Nothing else. Perhaps this had something to do with the fact that I was applying as my mom’s dependent. When my mom had her interview, she was asked not only about her persecution, but also the basics of Zhuan Falun (Revolving the Law Wheel), the main book of Falun Gong teachings. She was even asked to demonstrate the first part of the Falun Gong practices. After my interview, the Refugee Agency printed me a proof of my asylum-seeker status, which showed my name, photo, and identification information written in both English and Thai. The interpreter told me that while this temporary certificate functioned just like the official refugee card, I had to come back to get it renewed every 30 days. So the interpreter asked my mother and me to come back in about 30 days to get the official decision on my application.

As it turned out, after just a little over a week, the Refugee Agency called to say that my application was approved and my official refugee ID card was ready for pick up. Both my mom and her friend were thrilled and surprised at the news: for most people, it would take about six months to a year after submitting the application to obtain the refugee status; it took me only a month after I arrived. After I got my ID, my mom and her friend and I had a big dinner to celebrate.

The refugee status approval didn’t really help our life much. While the Thai government allowed the UN Refugee Agency to operate out of Bangkok, it placed various restrictions on refugees. For example, refugees were not eligible for employment. The Thai police would stop people on the streets and check their status. If they found out you were a refugee, they would transfer you to the immigration jail. Moreover, unlike America, where refugees have the opportunity to apply for green cards, Thailand didn’t allow refugees to stay long in the country. So, all refugees had to be relocated to third countries. To many, the refugee ID, or what I call the refugee paper, was the equivalent of a ticket to another country.

It was actually illegal for refugees to work in Thailand. Even the Refugee Agency would send us notices from time to time to tell us not to work, as it would increase our chance of being sent to immigration jail. However, to scratch out a living, many refugees had to take the risk. My mom was one of them—she waited tables at a restaurant operated by Thai-Chinese and sold wheatgrass juice in Lumpinee Park. None of these lasted long—mostly three or fourth months—due to the rigidly enforced police inspection. The wage was minimal too, just enough for us to get by.

It was such peculiar circumstances, or rather, cruel realities, that made the Bangkok Refugee Center (BRC) the go-to spot for most asylum seekers after they gained their refugee status. The Center is a non-governmental organization funded by a Catholic church and the UN Refugee Agency. It provides refugees with medical care, educational opportunities, living stipends, and occasional information sessions to help refugees know their rights. They also offer self-improvement courses to enrich the otherwise boring life of the refugees and expand their knowledge to better their chances of employment when they get to the third country.

The center was where my mom took me immediately after I got my refugee paper, and we applied for living stipends. It took a long bus ride to get there, and the traffic jam and Thailand’s year-round high-90s temperature made it quite torturous.

At the Refugee Center, we told the receptionist about our purpose of visit to have an interview arranged. After a two-hour wait, I walked into the interview room.

The Chinese interpreter was an acquaintance of mine. As he was busy doing something else, he told the interviewer that I spoke English and to interview me without interpretation. The contents of the interview were similar to the one I had at the UN Refugee Agency, except that the staff here focused more on getting to know about our needs, such as rent and food expenses each month. Then we had to wait for the final approval from the higher-up.

When I finally managed to finish the interview with my serviceable English, the interviewer, surprisingly, asked, “Would you like to volunteer here at the Center as an interpreter?” I was dumbfounded, because I never thought that my English was good enough to be an interpreter. I said frankly, “Are you sure I can do this with my level of English?” She then explained that all I had to do was interpret simple dialogues—no translation of dense texts needed. Besides, the interpreter was about to relocate to the United States, and the Center had an urgent need for a replacement.

I didn’t make a decision on the spot, as I was unsure whether I was competent enough for the position. After I got back home, I had a discussion with my mom. My mom said it would be good for me to take up the job—not only would I be able to help others in need, but also I could practice my English.

Working at Bangkok Refugee Center, 2008.

A few days later, I returned to the Refugee Center and took up the challenge.

Even though I was working as a volunteer, I, as a refugee, still received some additional living subsidies. So it could be said that I was making some small income.

Working there turned out to be an eye-opening experience because of the various people I got to meet in the course of the routine work. Among the many people applying for political asylum, a majority were Falun Gong practitioners, followed by activists from the 1989 Democracy Movement and the victims of China’s family planning policy.

A Mr. Cai had already spent a decade or two in Thailand. Almost every month he would visit the Refugee Center twice for the monthly stipends and medical help. He wasn’t very tall. His right hand was injured and couldn’t move freely, as if it was a piece of wood attached to his right arm.

One day I saw him waiting on the bench for doctors at the clinic, and went over and struck up a conversation. He was quite talkative and just chatted away even before I got to ask any questions. From what he said, I learned that he was fed up with the Communist Party during the Cultural Revolution and wrote words like “Down with the Communist Party” on the wall. For this, he was shot in his right hand by the military and sent to Reeducation-Through-Labor. After his release, he fled to Thailand, where he launched a journal called “Zhongguo Minzhu Tongxun” (China Democracy Bulletin). Due to financial constraints and the technical challenge of computers, he hand-wrote all his publications stroke by stroke with his left hand for several years. But he was really unlucky—he had yet to find a third country willing to accept him.

Only after knowing him did I realize how ruthless the Communist Party is to civilians. Granted, I had read articles telling similar stories, but it was my first time meeting such a victim in person. Previously, I had thought that the government had left these people alone since the Cultural Revolution was long over, but my conversation with Mr. Cai changed my view completely.

Besides interpreting for people who came in for medical treatment, I also helped refugees seeking to meet UN resettlement representatives with registration and translation. The UN resettlement representatives would pay regular visits to the Refugee Center so that refugees could have a chance to inquire about the progress of their cases.

Mr. Xie was a regular visitor who came to meet with the UN representatives. Every time I saw him, he was wearing sunglasses and carried an enormous bag on one shoulder. From my interpretation for him, I gathered from his accent that he might have been from Guangdong and thus asked him in Cantonese whether he was Cantonese. He was thrilled to learn that I was from Guangdong as well. He said it wasn’t easy, outside China, to meet someone from the same hometown, and would come talk to me whenever he was at the center. He was married with a son and a daughter. According to him, his son and I were about the same age, and he saw me as his own son too.

Mr. Xie was a democracy activist. He participated in the 1989 Democracy Movement. After the crackdown, he joined the Coalition for Citizens Rights and campaigned for commemoration of the movement. His work had drawn frequent police harassment of him and his family, forcing him to flee to Thailand and become a refugee.

Besides interpreting for Chinese refugees, sometimes I would go see Lao refugees at the Thailand-Laos border. Due to the Thai government’s restriction on the number of Laos entering Bangkok and refusal to let Lao refugees settle in a third country via Thailand, most Lao refugees were stuck in the refugee camps on the border. While the UN and Refugee Center would provide them with some living assistance, most refugees made a living from growing vegetables and fruits in the field or raising chicken. They also faced big problems with their children’s education.

All the new experiences and people opened my eyes and greatly enriched my life during my two-year stay in Thailand. With no updates on our resettlement in a third country, my mom and I had made up our minds for long-term stay in Thailand. In any case, we had already adjusted to life in Thailand, and the hot weather was not really a big problem. And I had learned enough conversational Thai to get around. It seemed fine to stay in Thailand.

But fate seems to have a tendency to disrupt peaceful life. Just when our life in Thailand was becoming stable and we were resolved to stay there for the long haul, we received a resettlement acceptance letter from the United States with a scheduled flight in two months. I was of course happy to receive the letter. After all, this was what I had been waiting for all this time. I also felt, however, a bit dazed. It had taken me two years to get used to Thailand, and now, all of a sudden, drastic change. It was really hard to take. Nevertheless, I was not going to give up this opportunity to go to America.

As arranged, two months later, I arrived in the United States in February 2009.

I still find it funny to think back on my reaction upon arrival. When I took off in February, warmth had just returned after a short winter in Thailand. However, across the globe, in America, winter had not yet ended. I was unable to feel the change of temperature in the flight cabin, where the temperature stayed the same. When the plane landed and the door opened, the cold air rushed right into my body. It was only then did I have a taste of true wintery weather.

We arrived at two in the morning, and were exhausted after more than 20 hours on the plane. As we came inside the arrival lobby, a man walked up to us and asked if we just arrived from Thailand. The airport PA said that the airport was closing, and there was no one around us. I said yes. After verifying our identity, the man briefly introduced himself as a staff member of the local resettlement agency, responsible for picking us up from the airport and taking us to the apartment that was rented for us. As it was quite late, we followed him without any further questions and went into his car.

My mom and I in Boston Chinatown, 2009.

An hour later, we reached our destination—Worcester, Massachusetts. Our apartment was a semi-basement with only one window on the street side, facing a hill. It wasn’t ideal, but it was way better than spending the night outside in the icy snow. Exhausted, we fell asleep on the couch after the staff member ran through the next day’s arrangement with us.

The next morning, another staff member from the agency woke us up; he took us to the agency’s office to do some paperwork.

At the agency, we met with our case manager. After introducing herself, she told us some basic facts about the agency and about the various paperwork and formalities we needed to complete in the coming month.

This agency, a nonprofit sponsored by the Lutheran Church, is mainly responsible for providing refugees in the United States with services such as case management, employment recommendations, and basic legal assistance—much similar to the refugee center we had in Thailand. We learned from her just how complicated the process of refugee resettlement actually was. When an asylum seeker obtained his refugee status in Thailand, his case would be forwarded to the refugee agency’s resettlement mechanism, which, after verification of the individual’s refugee status, would submit the refugee’s profile to all refugee-taking countries such as the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Finland, and Norway. In the case of the U.S., after receiving the refugee’s resettlement profile, it would conduct another round of more detailed identity checks before approving entry. If the refugee’s profile passes the check, it would then be transferred to domestic nonprofits to determine whether the refugee would be accepted. The agency we were at was one of those nonprofits.

In the following days, the agency assisted us with applying for documents such as the social security card and employment authorization, which were vital to our being able to work in the United States. Aside from this, the state government also provided us with eight months of living stipends and food stamps. Now, we had all basic needs taken care of to settle down.

In our hour-long meeting, our case manager answered almost all our questions. But she did not address one important question: my education. I couldn’t help but ask, “What I need the most right now is education. Can I attend public schools?” “Good question. I really haven’t thought of that,” she replied. As she proceeded to review our profile, the smile on her face turned into a sympathetic look. She explained, “Because you’ve just turned 18, you are not eligible for public high schools. Your only option is either community college or university, but the agency can’t help you with tuition.” This news was a shock. Since I didn’t have a high school diploma, and I was out of school for two years during my time in Thailand, it wouldn’t be easy for me to get into community college or even high school. Further, financially, we would already be grateful for being able to afford our rent. Paying for community college out of our own pocket was impossible.

The following week, other than going for physical checkup and doing other necessary paperwork, my mom and I stayed in our apartment the whole time. As newcomers living without the Internet and maps, we didn’t even know what street we lived on or if there was public transportation available. Besides, as there was a blizzard with extremely low temperature, and we were still jetlagged, there was nothing for us to do but sleep. I’m not talking about sleep in a normal sense—we would sleep for more than 10 hours each time, making up not only for the 24 hours on the plane ride, but probably also for all the missed sleep in Thailand. Further, as it was winter with fairly short daytime, you could say that we spent this week “living in darkness.”

The director at the resettlement agency found out about our situation and knew that something needed to be done. He contacted our landlord George, and introduced him to us. George was very willing to help us. He showed us around the supermarkets and stores in the neighborhood, and bought us a map to get oriented in our neighborhood. When he found out we didn’t have Internet, he helped us ask our neighbor upstairs to borrow their Wi-Fi connection so that we could contact our family and look for information. Aside from the resettlement agency, George was the one most helpful to us with our life. People at the agency were of course willing to help as well, but they were restricted by rules and overwhelmed by their workload. I understood that for these reasons, they weren’t able to assist us meticulously in order for us to get to know our community better.

After visiting us a few times, George became close to us. He told us that he was about the same age I was when he arrived in America from Lebanon. He was all by himself and had almost nothing. It took him several years to complete his degree while working part-time, and then he started his own import/export company. One difficult step after another, he gradually got to where he was. Therefore, he was very much sympathetic when he heard about our situation, and came to help us without hesitation.

With the subsidies that the state government of Massachusetts provided to newly arrived refugees for an eight-month transition period and some other government subsidies such as food stamps, we had just enough to get by. Eight months sounded like a long time, but, in fact, they flew by fast. Despite our efforts, nearly four months had passed, and my mom and I failed to land a simple job. My mom and I stopped in all the shops downtown to ask if they were hiring, but none were. I applied for cashier job at places like Sears as well, but I never heard back after the interview.

Finding a job was even harder for my mom. There weren’t many Chinese in Worcester, and she barely spoke English. For this reason, no one wanted to hire her. There were many babysitting jobs available in Boston, and my mom tried. But some of the places she couldn’t get to without a car, and one time she was dismissed by her employer due to some family issue. It wasn’t stable employment.

We had informed the resettlement agency of our situation, but they were unable to do much except help us apply to companies in partnership with the agency. For some reason, however, we couldn’t land a single interview.

Later we told George about our difficulties, and he immediately asked me to help in renovation work on the houses he owned. The pay he offered was moderate, but at least it kept us. After a while, George found a government-sponsored center that provides educational opportunities to people under 21. It offered free classes for getting a GED and driver’s license, and job training.

George was very excited when he learned about this because he finally found a school for me to go to. I, on the other hand, was hesitant because I worried if I could catch up after having been out of school for three years. My English was still not good enough—even though George and many others said that I already had good command of English—and I still struggled with having enough confidence. But since it was free, and my goal was to complete my studies, I decided to give it a try regardless, as a challenge to myself.

After some paperwork, I became a student of this school.

Before starting at the school, I was afraid of being discriminated against by my fellow classmates, as I was the only Chinese student. Even the guidance counselors there had the same concern. They told me on the first day that they’d try their best to help if someone bullied me. I had probably watched too many movies on campus violence. As it turned out, after getting to know my classmates, I found that not only did they not discriminate against me, they in fact showed great willingness to talk to me. They were very curious about my life in China. I also didn’t try to hide anything, and did my best to use my limited vocabulary to describe to them my life and experience in China, as well as the reason I came to the United States.

The biggest difficulty I encountered in school was in understanding colloquial American English, or American slangs, which were hard to find in English textbooks. In addition, due to geographic differences, sometimes what I meant to say was understood differently in American English, causing some laughter or head-scratching among my fellow students and teachers. To overcome this hurdle, I watched American news channels and TV dramas every day, including the very popular series, “Family Guy.” In fact, the more popular, the better—these kinds of shows contained every-day, colloquial conversation different from scripted news broadcast. Gradually, I was able to watch an entire series without looking at subtitles. Of course, talking to my fellow classmates helped, too.

The first task in school was to prepare for the GED test, a credential equivalent to a high school diploma designed for those like me who did not complete high school. Compared to a high school diploma, the GED has fewer subject tests and was easier pass.

The hardest GED subject test for me was not reading, but writing. As a product of China’s exam-oriented education, I had no difficulty in completing the reading test. All I needed to do was read the answers first, and then skim and extract the corresponding information from the article. Writing was different. First, my first language is Chinese, and it was extremely difficult to write in authentic English. Besides, writing had always been my weak point—even now writing this very essay feels like I was killing I don’t know how many brain cells. Fortunately, there were only three topics in the writing subject test. As a result of the exam-oriented training, I worked hard to practice writing well on the three topics ahead of time so that I could just transfer the essay from my memory onto the exam sheet.

Besides reading and writing, like in China, the GED also tested basic math, which was covered in junior high school [7th to 9th grades] in China. So, in less than 2 months, I passed the GED test.

The second step was to get a driver’s license. After getting my GED, I thought I wouldn’t have any problem with this, so I got behind the wheels with full confidence. My first road test, however, almost gave my terrified instructor a heart attack. Afterwards, I took baby steps under my instructor’s guidance, and only got my driver’s license after my third test.

The third part of the program was occupational training. The school offered trainings such as medical assistance, administrative assistance at hospitals, and cooking. I chose administrative assistance training because administrative assistance chiefly involved a lot of work done on the computer, which suited my interest. Besides, I was already familiar with almost all the required subjects, which were mostly based on basic computer operations and Microsoft Office. Further, I saw the professional training school as a stepping stone to my ultimate goal of going to college. So I picked the easiest subject to shorten my time there.

As I expected, it took me less than 6 months to complete the professional training courses.

Easy time was always fleeting. My eight-month refugee stipends came to an end about the same time I completed my courses, forcing me to suspend my original plan of going to college immediately after the professional training school. Fortunately, the school referred me to work at a college kitchen after hearing about my situation. It didn’t pay much, but I took the job anyway.

Although I couldn’t go to college due to financial and familial reasons, I had achieved a lot over the first few years in the United States. I am wrapping up this essay, but I will move forward.

Looking back at the past two decades plus of my life, even though there were ups and downs, I moved forward steadily. Like a sailor in the seas, I had to accumulate enough experience in the waves to become a captain to chart my own course. Though several times, I had thoughts of giving up in the face of stormy waves when in transitions, but my parents would always support me in those times and helped me continue my journey. Now, I am anchored in the harbor of freedom, but this is only the beginning of my journey. After refueling, I will continue guiding my ship in the vast ocean of life.

© All Rights Reserved. For permission to reprint articles, please send requests to: [email protected].

Ah Shun (阿舜), born in Guangzhou in 1990, is a “cross-generational,” straddling the “post-‘80” and “post-‘90” generations. He lives in New York City. (Photo courtesy of Ah Shun.)

Ah Shun (阿舜), born in Guangzhou in 1990, is a “cross-generational,” straddling the “post-‘80” and “post-‘90” generations. He lives in New York City. (Photo courtesy of Ah Shun.)