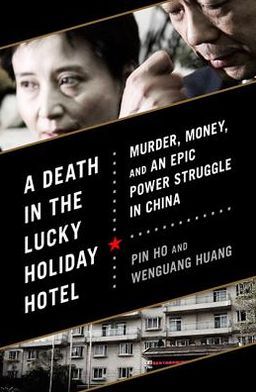

Excerpts from A Death in the Lucky Holiday Hotel:

Murder, Money, and an Epic Power Struggle in China

by Pin Ho and Wenguang Huang

Reprinted with permission from PublicAffairs.

From Part 1: “The Fate of a Kuli”

On Wang Lijun, pages 16-21

GENETIC SCIENTISTS BELIEVE that 17 million people in Asia are direct descendants of Genghis Khan. Wang Lijun liked to brag at the height of his fame that he is a product of that fearsome thirteenth-century Mongolian warrior.

Born in Arxan, Inner Mongolia, on December 26, 1959, Wang shared the same birthday as another formidable figure, Mao Zedong, who led the Communist revolution to victory in 1949 and ruled China with brutality for twenty-seven years. At the height of Wang’s career, a local newspaper in the northeastern city of Tieling described Wang’s birth in a style once reserved only for Mao:

When the glowing sun broke through the clouds and rose slowly on the horizon, spewing golden rays, a crying baby boy was born in a house at the foot of the Arxon Mountain. By Mongolian tradition, a newborn’s name is based on the specific time and the natural environment of his birth. Wang’s father, well versed in Mongolian culture, bestowed upon him a romantic name—“Ünen Baγatar,” which means “A True Hero.” Ünen Baγatar’s Chinese name is Wang Lijun, which means “Finding your call in the military.” As a little boy, Wang inherited the heroic styles of his famous ancestor Genghis Khan, and began practicing horse-riding and archery.

…As a teenager, he was a member of a Mongolian youth boxing team and commanded superb martial arts skills. After high school in 1977, he was assigned a job at a state farm in northeastern China and a year later joined the army. According to a childhood friend, Wang always dreamed of becoming a military officer. While stationed in Tieling, a northeastern city with a population of 3 million people, he twice took the rigorous national college entrance exam hoping to get into a military academy, but he never passed. In 1982, a year after his compulsory military service ended, Wang married Xiao Shuli, who was a switchboard operator in the army. Four months after their marriage, the two settled in Tieling, where, through the connections of his father-in-law, an army officer, Wang obtained a job as a truck driver at the municipal commerce bureau. His wife also left the military and was employed at the local police department.

Wang’s police career started in 1983, when the local public security bureau enlisted him as a volunteer in a neighborhood watch group. Wang took the assignment seriously and trained a group of young people who diligently patrolled the streets and coal mining facilities. In 1984, a friend at a local mining company introduced him to the Tieling deputy police chief, who later recommended Wang join the police force when the Tieling Municipal Public Security Bureau began recruiting in 1984. Despite his lack of a college education, which was required of other candidates, he got the job.

Three years later, at the age of twenty-eight, Wang was promoted to head a police station in Xiaonan township at the southern-most tip of the city, where robberies and gang-related killings were rampant. A month before he assumed the position, a young police officer there was ambushed and stabbed to death. The assailant was never caught. An article in the Law Weekend described vividly Wang’s first week at his new job there:

Wang received a phone call while he was on duty one night. “Are you the new police chief? Do you know how your predecessor died? You will end up like him. If you don’t believe me, come see me at the train station.” Wang slammed the phone down, holstered his handgun and headed directly to the train station. In the icy cold wind, he searched for the gang leader and shouted, “If you have the guts, come out to meet me!” Wang waited until dawn, but the gang leader never showed up.

Thus, Wang’s reputation as a brave and fearless officer soared. The new police chief was not only brave, but also smart. In his spare time, he invented an automatic alarm system, connecting all public security offices nearby. He had the alarm system installed in factories and government offices. Each time someone broke in, the red lights in the public security bureau would flash. Police could be on site within minutes.

The crime rate plummeted in Wang’s district and within three years, the state media said he solved 281 criminal cases and the township was being cited as a model in the province. In 1991, he was transferred to another branch, where he practically lived in the office. Wang created a record by busting ten criminal groups in nine days. In January 1992, he was honored by the Ministry of Public Security as one of

“China’s Ten Most Remarkable Policemen” and traveled to Beijing to meet many of China’s senior leaders. Upon his return, Wang was appointed the deputy director of the Tieling Public Security Bureau and sent to receive training at the Chinese People’s Security University. At the beginning of his tenure in Tieling, the city was infested with organized-crime gangs that controlled the city’s nightclubs, hair salons, and restaurants, engaging in prostitution and blackmail. Gun shootings were rampant and gang members even planted bombs outside government buildings. In winter, many farmworkers were largely unemployed and engaged in drinking, pickpocketing, and street fighting. Ordinary residents suffered at the hands of mafia leaders and street gangs.

As an important new initiative, Wang launched an anti–organized crime campaign in September 1994. He set up a forty-member work team and turned a three-level office building into a temporary jail, detaining and interrogating suspects. Over the next four days, he cracked more than 800 cases, arresting 923 people in connection with the 87 gangs, or mafia groups, that controlled the city. At subsequent trials, seven ringleaders received the death penalty. Nineteen police officers were found to be corrupt and were jailed or sacked on charges that they had colluded with criminals.

Many legal experts, including Wang Licheng, the lawyer who disputed Wang’s ethnicity, criticized the campaign for denying due process to the accused, but dissenting voices fell on deaf ears. The authorities were pleased with the results and Wang was hailed as a tough crime fighter. The local government commissioned a book, The Legends of the Northeastern Tiger, to chronicle his heroic acts. In one chapter, Chen Xiaodoing, the author of the biography, described how Wang captured the two mafia leaders:

On September 19, 1994, Wang was tipped off by an informant that Yang, a local mafia leader, was hiding at a nearby hotel. Wang took a small police squad there and they took up positions in an employee meeting room on the hotel’s first floor. The informant went to see Yang, whispering to the mafia head that he had something urgent to share. The informant brought Yang to the employee room on the first floor. Barely had Yang entered the room than Wang leapt on him like a tiger on his prey and subdued him. “Do you know who I am?” Wang shouted. Yang looked up and stammered, as if waking up from a dream. “Oh, you, you are Wang Lijun. It’s totally worth it.” Wang asked, “What do you mean by that?” Yang answered, “It’s worth it, dying by your hand.”

…Wang’s bravery earned him a number of accolades and his uniform was covered with medals. In 1995, he went on a nationwide lecture tour, touting the success of his anticrime programs in Tieling and explaining how a more alert and aggressive police crackdown could achieve good results. On the day he made his presentation to senior leaders at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, he was told by the local court that the mafia leaders he had captured would be executed. A government newspaper described Wang’s reaction to the news:

Wang was eager to hear the gunshots of justice. When he finished his talk at the Great Hall, he quietly left the stage and stood in the hallway, where he called Ji Lianke, deputy director of the criminal investigation unit. “Director Wang, can you hear the gunshots? We are shooting the fourth one now,” Ji reported to Wang, who held his phone tightly to his ear. “Bam!” Wang could hear the sound of gunshot through his phone. After the execution, several hundred residents spontaneously showed up in front of the city hall, carrying a twenty-meter-long banner to thank Wang Lijun.

From Part II: “The Princelings”

On Bo Xilai pages 94-99

In 1983, Bo Xilai made a personal trip to New York City and stayed at Liang’s home. Liang remembers Bo Xilai as a smart young man filled with curiosity. He bought a metro pass and toured the city himself on the subway. Liang said Bo Xilai took a keen interest in Harlem and visited the borough twice to study the cultures and living conditions of African Americans. He marveled at the pristine beaches of Long Island and the clean air.

Liang says Bo’s personal interests in New York probably inspired many of his public projects in Dalian, a seaport city in northeast China, wedged between the Yellow Sea to the east and the Bohai Sea to the west.

Built and founded by Russians who defeated Chinese imperial troops and occupied what was then Manchuria in 1900, Dalian—or Dalny, as it was known—became the southern tip of the Trans- Siberian Railway and a gateway to the East. Following the Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–1905, the city was transferred to Japanese control and renamed Dairen.

China regained control of the city after the Second World War. A friend, Dong Ayi, who grew up in Dalian in the 1950s and 1960s, recalled the city as a heavy industrial port of shipbuilding, chemical processing, and industrial equipment manufacturing. When Bo Xilai took over the mayor’s position in 1993, the city was going through a tough financial time. The majority of state-run enterprises had gone bankrupt after losing government subsidies, and thousands of workers had lost their jobs, previously seen as cradle-to-grave iron rice bowls. The city’s unemployment rate was higher than the national average, and its air and water quality was poor due to pollution from heavy industry plants.

Among many of Bo Xilai’s policy initiatives to rejuvenate the city and improve the city’s image, two are worthy of mention: beautification and soccer.

During his first five years in office, Bo Xilai stirred up a “green” storm, aiming to build Dalian into China’s northern Hong Kong. He made ambitious plans to move nearly one hundred pollution-causing factories out of the city proper. The government tore down old factories and barracks to build different styles of public squares, plant trees along streets, and create thousands of square kilometers of lawn in public places. In 1995, the city created 2 million square meters of lawn, with grass covering 37 percent of the city. Bo Xilai’s vision was a challenge for many who still saw idle land as a Western luxury and waste of space. In the Mao era, Chinese were urged to cut trees and burn grass to make space for crops. For a while, some people in Dalian joked that their mayor “paid more attention to grass than crops.”

Bo Xilai was also credited with increasing the number of sewage treatment facilities as part of a campaign to clean up the city’s forty foul rivers and converting old fishing villages into commercial beach resorts and tourist sites.

Dalian soon became a model for the rest of country’s mayors to emulate. It became known as China’s Singapore, a city built around parks. In 2001, the United Nations Environment Programme recognized the Dalian Municipal Government for its outstanding contributions to the protection of the environment. In 1993, the Wall Street Journal named Bo Xilai as one of the top twenty most promising officials in China.

But Bo’s experiments in Dalian were criticized by many as public relations exercises to attract attention from Beijing. For example, Dalian, located in China’s dry north, suffers severe water shortages. Critics say the city wastes its scarce freshwater resources on useless plants and grass, while public squares rob Dalian of precious land that could be put to profitable commercial use.

To counter his critics, Bo claimed that beautifying Dalian had helped attract more foreign and domestic investors. His environmental initiative led to a rise in property values. And of the 2 million residents in Dalian, more than half lived in new housing complexes and 450,000 moved to new buildings with government subsidies. Rising property values provided the city with more taxes, enabling the government to underwrite the relocation of pollution-causing factories to the suburbs.

In addition to his environmental projects, Bo Xilai was also known as the soccer mayor, who saw a competitive soccer team as “an attractive business card” for the city. His pro-soccer stance captured the mood of the city, which is passionate about the sport. In the early 1980s, the Dalian Football Club was a national top-tier team. In 1993, the club was reorganized into a professional team. The city offered Wanda Group, a Dalian-based real estate and entertainment conglomerate, subsidies and tax benefits, making it a model enterprise for sponsoring the club, which won the first fully professional Chinese Jia-A League title in 1994. Subsequently, the team achieved a total of eight league titles, becoming the most successful club in Chinese soccer history.

“Soccer is not just sport and entertainment, but also a spirit,” said Bo Xilai on numerous occasions. In an effort to make soccer the city’s official sport, the government established a soccer development zone, and allocated funds to train new players and popularize the sport among children. Under Bo, Dalian had a well-funded and prolific soccer academy that produced numerous prominent players. Facilities were constructed to host international matches. In the early 2000s, its overall strength in the sport was unmatched in the country. Children in Dalian idolized their soccer players like movie stars.

…Bo was keen to make Dalian a showpiece. In 1994, in anticipation of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, he built Xinghai Square on the site of an old salt mine. It is the largest public square in Asia, covering 1.1 million square meters. Its name, which means a “sea of stars,” is reflected in the shape and design of the center of the square, which looks like a gigantic star. As an illustration of Bo’s pro-people style, the square boasts 1,000 pairs of footprints left by Dalian residents.

The square raised many eyebrows—in the middle of the square stands a pair of huaibiao, or white marbled ornamental pillars, 19.97 meters (66 feet) high and 1.997 meters (6.6 feet) around, with dragons carved on them. The ornamental columns, which once would have represented the power of the emperor, were copied from a pair erected in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, near the Forbidden City. The ornamental columns in Dalian are taller and bigger, and Bo’s critics claim they symbolize his secret desire to overpower the emperor, or in modern terminology, the general party secretary. When former president Jiang Zemin visited Dalian, he was said to be shocked by the imperial symbols. It is unlikely he missed their significance.

After Bo Xilai’s downfall, Chinese state media said his vaunting political ambitions left many imprints in Dalian. Whereas the US president supposedly carried a suitcase that contained “the football”—giving him the power to launch nuclear weapons at a moment’s notice—Bo Xilai installed a switch on his desk that could turn on or off all the city’s water fountains so he could feel that he was in control.

From Part III: “Poisonous Water”

On Gu Kailai pages 156-159

In 1984, during a field trip with a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Gu Kailai told the state media that she had become acquainted with Bo Xilai and was starstruck…. In a profile in the Singapore-based United Morning News, Gu compared the young party chief to her father—“educated, idealistic, and reliable,” like “those heroes in movies.” Bo and Gu also bonded over their shared experiences: both their parents had come from Shanxi province where they joined Mao’s revolution, and were later persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. While Gu Kailai and her sisters had grown up in prison with her mother, Bo Xilai and his siblings were left to wander the streets when their father was detained and their mother died in the hands of the Red Guards.

The relationship soon blossomed, even though Bo Xilai had to maneuver through his messy divorce. In 1986, Gu Kailai gave up an opportunity to study in the US and married Bo Xilai, who was nine years older. The next year, their son, Bo Guagua, was born.

At the end of 1987, she passed the newly installed National Lawyer’s Examination, an equivalent to the American bar examination, and became one of the earliest licensed attorneys in China. In 1988, after Bo Xilai moved to Dalian to take up a district party secretary’s job, she followed him and set up the Kailai Law Firm in the city. She was one of the first lawyers in China to start a private practice under her own name. As her husband rose through the ranks, Gu Kailai’s practice flourished.

In 1995, she established a branch office in Beijing.

In her short career as a lawyer, two high-profile cases boosted her reputation. In 1997, she represented a Chinese manufacturer of laundry detergent, which had purchased a computerized assembly line from a machinery company in the US in 1987. The US company filed for bankruptcy before it transferred any of the main software or operating instructions. The equipment that had arrived was useless and the Chinese manufacturer lost US $5 million. When it attempted to retrieve the relevant technology needed to run the equipment, a courtappointed bankruptcy trustee sued the Chinese for stealing trade secrets and for intellectual property infringement. The court entered a default judgment, ordering the Chinese company to pay US $1.4 million in damages. Because the Chinese company was a state-owned enterprise, the federal court in Alabama notified the Chinese Foreign Ministry in 1996, threatening to freeze the assets of Chinese state companies operating in the US if the government refused to pay. The latter part of the court order triggered a strong response from the Chinese government. According to an official Chinese media report, Gu Kailai agreed to take on the case pro bono. She flew to Alabama and hired a legal team to argue the case. In March 1997, a federal appeals court in Alabama overturned the verdict.

In the mid-1990s, Sino–US business disputes were relatively rare and there was little by way of precedent. The case made Gu famous. The Chinese public saw her as a hero who had dared to stand up to American bullying to protect the interests of Chinese enterprises. Based on the experience, Gu Kailai wrote a book, Winning a Lawsuit in America, which became a best seller. However, some critics later accused Gu Kailai of exaggerating her role in the case. On August 14, 2012, the Hong Kong–based New Century Magazine released an article that pointed out Gu Kailai had no license to represent clients in court and that her role was limited to advising American counsel and monitoring the court proceedings. Besides, China did not really win the lawsuit, because the Chinese company never recouped the US $5 million loss from the US equipment manufacturer.

Gu Kailai seemed to thrive on controversy. In 1998, she projected herself into another contentious case involving Ma Junren, a track coach in Dalian. Ma had captured worldwide attention when his team broke national and world records sixty-six times in middle- and longdistance women’s track events. Amid the praises came an unexpected article in the Chinese Writers magazine, which alleged Ma had engaged in “illegal activities,” such as physical and sexual abuse of athletes, confiscation of athletes’ prize money, and more important, doping. The expose shocked the nation and dented the reputation of the once seemingly invincible coach. Supported by her mayor husband, Gu Kailai threatened to launch a lawsuit against the magazine to defend the iconic figure, who was closely associated with Dalian. While preparing for the legal battle, she wrote a book, My Defense of Ma Junren, which listed one hundred alleged errors and inaccuracies in the magazine article. The release of her book pitted her against the magazine writer, making them the center of the controversy.

The lawsuit never materialized. During an interview with state media, Gu Kailai said that she had decided not to sue the magazine because the lawsuit had the potential to turn into a farce and could damage the reputation of her city and the coach. That proved to be a smart political move, which probably spared her national embarrassment. Two years later, many of the allegations in the magazine article were proved to be true: during random drug testing, investigators suspected that Ma had used performance-enhancing drugs as part of his training regime. Despite his strong denial, six of his athletes were barred from China’s team at the Sydney Olympics in 2000 after they failed blood tests. Ma Junren quit the Chinese Olympic team and is now breeding mastiffs in Liaoning province.

It was also in 1998 that Gu Kailai decided to leave her practice and devote more time to her son’s education. Her decision was uncontroversial; many senior leaders’ spouses took similar paths—relinquishing their careers and keeping a low profile to support their husbands’ political futures….

A Death in the Lucky Holiday Hotel: Murder, Money, and an Epic Power Struggle in China

Pin Ho, Wenguang Huang

Public Affairs

Publication Date: April 2013

Hardcover: 352 pages