1. Hong Kong authorities conflate internationally protected rights with “subversion”

In the early morning of Wednesday, January 6, in a move intended to decimate political opposition and extinguish political activism and participation, Hong Kong authorities deployed some 1,000 police officers to arrest 53 individuals in connection with unofficial election primaries held in July 2020. Among the arrested are prominent former lawmakers including Eddie Chu, Alvin Yeung, and Kwok Ka-ki; current district councilors including Lester Shum (who is also a student leader in the 2014 Umbrella Movement); Benny Tai, legal academic and one of the key organizers of the Occupy Central movement; as well as John Clancey, an American lawyer who is a permanent resident of Hong Kong. All 53 were arrested on suspicion of “subversion of state power” under Article 22 of the National Security Law, for organizing, planning, implementing, or participating in the unofficial primaries.

A day later, on January 7, police arrested an additional two individuals for their participation in the unofficial primaries: activist Joshua Wong, who is serving a 13-and-a-half-month prison sentence for organizing and inciting a June 2020 “unauthorized assembly,” and Tam Tak-chi, who has been in custody since September 2020 on suspicion of sedition. As of January 8, 52 of those arrested on January 6 have been released on bail. (See a complete list of those arrested at the end of this bulletin.)

Like the mass crackdown on over 300 rights lawyers and activists in mainland China in 2015, carried out in a terror campaign to intimidate and demolish the rights defense community, the latest police action in Hong Kong is another fundamental attack on the rule of law and on rights protected by domestic and international law. In one fell swoop, the Hong Kong authorities more than doubled the number of individuals arrested under the National Security Law since July 2020, with threats of more arrests to come as their investigations continue.

“The international community needs to not only condemn the mass arrests, but also demand compliance with the relevant international standards and norms incorporated in the National Security Law, the Basic Law, and China and Hong Kong’s international obligations,” said Sharon Hom, Executive Director of Human Rights in China.

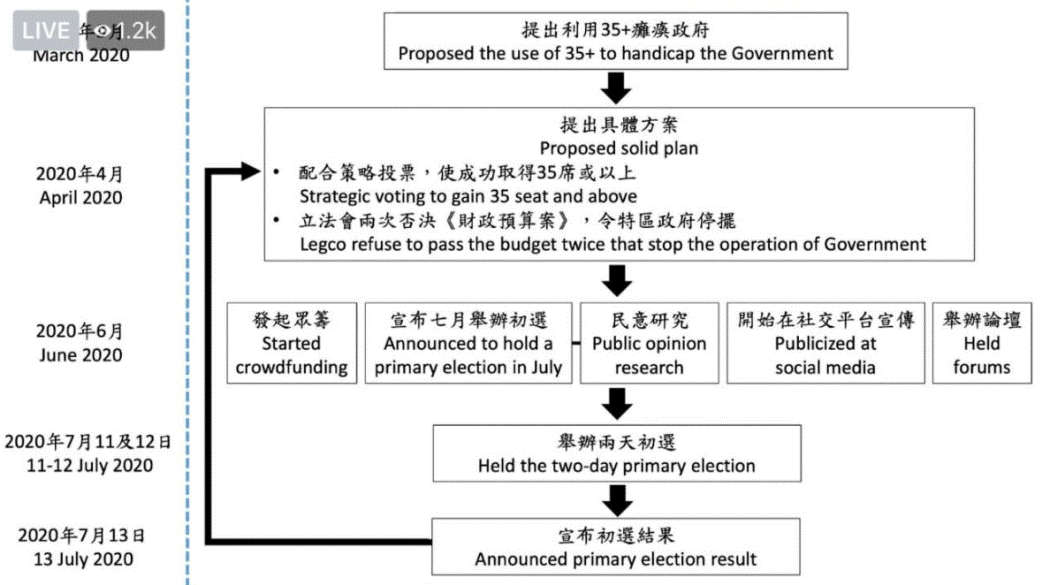

One vivid example of the Hong Kong authorities’ conflation of internationally protected rights with the crime of “subversion” can be seen in the police press conference on January 6. Steve Li, a senior superintendent of the Department for Safeguarding National Security of the Hong Kong Police Force (DSNS), displayed a flow chart that mapped the goal of the primaries and the relevant steps taken to hold them, including “public opinion research,” “crowdfunding,” and publicity in social media—unsurprising strategic elements in a political campaign—and portrayed them as steps to paralyze the government. The planners approached their mission with “determination and resources,” Li said. In addition, authorities pointed to the “35-plus” plan of the pro-democratic camp to attain a majority in the 70-seat legislature as tantamount to a plot to overthrow the Hong Kong SAR government.

Courtesy: Hong Kong Free Press

The unofficial primaries, held over two days, July 11 and 12, in street corners across the city, drew more than 610,000 voters who chose democratic candidates for the Legislative Council election that was then scheduled for September 2020. In late July, Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced the postponement of the election for a year, citing COVID-19 public health concerns.

“The politicized incrimination of the peaceful exercise of fundamental rights in order to snuff out political opposition—and the clear threats of more to come—has brought us to a critical juncture. We must go beyond condemnation and strategically invoke the rights protections in Article 4 of the National Security Law,” said Hom.

“Rather than dismissing Article 4 as a fig leaf, we must push for the implementation of one of the few rights protection tools available—we must use it by testing it.”

2. Take Article 4—and the rights it protects—seriously

In response to widespread concerns after the passage of the National Security Law, Chief Executive Carrie Lam and other Hong Kong SAR officials pointed to the incorporation of Article 4 as reassurance that rights would be protected. (She also tried to reassure the Hong Kong people that the National Security Law would only affect a small number of people. Clearly, she fundamentally misunderstands the nature of rights protections: Rights protections apply irrespective of how many or how few people are affected.)

Article 4 states:

In safeguarding national security, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall respect and guarantee human rights, the rights and freedoms, including the freedoms of speech, of the press, of publication, of association, of assembly, of procession and of demonstration, which the residents of the Region enjoy under the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as applied to Hong Kong, shall be protected in accordance with the law.[1]

The two fundamental rights impacted by the mass arrests are “the right to participate” and “the right of peaceful assembly”—both provided in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), thus also protected under the National Security Law.

The right to participate

Article 25 of the ICCPR states:

Every citizen shall have the right and the opportunity . . . without unreasonable restrictions: (a) To take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives . . . .

This right is emphasized by the spokesperson of the UN Human Rights Office on January 7, in a statement condemning the mass arrests:

These latest arrests indicate that—as had been feared—the offence of subversion under the National Security Law is indeed being used to detain individuals for exercising legitimate rights to participate in political and public life. . . . We stress that exercise of the right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, directly and through freely chosen representatives, is a fundamental right protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is incorporated into Hong Kong’s Basic Law. [Emphasis added.]

The right of peaceful assembly

Article 21 of the ICCPR states:

The right of peaceful assembly shall be recognized. No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those imposed in conformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

The UN Human Rights Committee—the UN treaty body tasked with monitoring the implementation of the ICCPR by states—and other independent UN human rights experts have elaborated on this right. In a legal guidance issued in 2020, “General Comment No. 37—Article 21: right of peaceful assembly,” the Human Rights Committee clearly defines the conditions under which the right of peaceful assembly may be restricted under national security grounds:

The “interests of national security” may serve as a ground for restrictions if such restrictions are necessary to preserve the State’s capacity to protect the existence of the nation, its territorial integrity or political independence against a credible threat or use of force.[2] . . . Moreover, where the very reason that national security has deteriorated is the suppression of human rights, this cannot be used to justify further restrictions, including on the right of peaceful assembly. [Emphasis added.]

(Para. 42, Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 37 (2020))

The Hong Kong authorities must demonstrate that, in implementing the National Security Law, they have complied with specific international standards for protecting the right of peaceful assembly. Two key issues are:

In the same legal guidance, the Human Rights Committee also enumerates “heightened-level” of protection that should be accorded to peaceful assemblies with a political message, including message of political opposition—the very thing that Superintendent Steve Li mistook for a criminal intent:

Given that peaceful assemblies often have expressive functions, and political speech enjoys particular protection as a form of expression, it follows that assemblies with a political message should enjoy a heightened level of accommodation and protection. [Emphasis added.]

(Para. 25, Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 37 (2020))

The rules applicable to freedom of expression should be followed when dealing with any expressive elements of assemblies. Restrictions on peaceful assemblies must thus not be used, explicitly or implicitly, to stifle expression of political opposition to a government, challenges to authority, including calls for democratic changes of government, the constitution, the political system, or the pursuit of self-determination. They should not be used to prohibit insults to the honour and reputation of officials or State organs. [emphasis added]

(Para. 49, Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 37 (2020))

The Hong Kong authorities must demonstrate:

3. Time for asserting—not relinquishing—rights

As the UN, governments, and civil society groups so powerfully speak out to condemn the mass arrests, this is also the moment for all of us to demand that Hong Kong SAR and mainland Chinese authorities abide by the rights provisions in the National Security Law and provide the protections enshrined in the law.

HRIC urges the international community to support Hong Kong people’s assertion of lawfully protected rights by taking the following actions:

“This is the moment to hold the authorities’ feet to the fire, a test, and an opportunity to give Article 4 real teeth to provide rights protections guaranteed in the international obligations of the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong SAR governments,” said Hom.

[1] The official translation has been modified by HRIC for greater accuracy. See Annex A of “Too Soon to Concede the Future: The Implementation of The National Security Law for Hong Kong--An HRIC White Paper,” Human Rights in China, October 16, 2020, https://www.hrichina.org/sites/default/files/hric_white_paper_on_nsl_ann....

[2] Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation of Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (E/CN.4/1985/4, annex), para. 29.

List of the 55 Arrested Individuals

Arrested for organizing/planning the unofficial primaries

Arrested for participating in the unofficial primaries as a candidate or supporter

United Nations

Governments

NGOs