Overview

Over the past several decades, media, governments, and experts have examined China’s increasing role in international trade, politics and security. Following recent exchanges with other NGOs suggesting strong and at times challenging views of China’s influence, HRIC decided to undertake an informal survey to better understand civil society perspectives on China's diverse global presence.

Mindful not to overstate conclusions in light of our limited dataset, we share preliminary high-level insights from the exercise with the hope of advancing future discussions. Overall, the survey responses reflect widely diverse perceptions about China’s impact. This result is consistent with observations from our broader outreach and collaboration work, suggesting that China’s presence and its impacts are still emerging and not yet fully understood even at the local level.

Overall, we found the survey to be a useful method for promoting a discussion among a broader NGO community. We hope that these initial observations will raise further questions and inspire the on-going conversations that are critical to addressing common human rights issues and leveraging the opportunities and challenges that come with China’s expanded presence.

We encourage interested NGOs to contribute to the survey by clicking the following link: http://www.surveyexpression.com/Survey.aspx?id=4790eff7-a31d-4b81-ab2b-9209cf921b70.

Methodology Notes

In early May, HRIC designed and distributed a 10-question survey to 170 human rights organizations located in 58 countries spread across the major regions of the world. The organizations that we approached were selected based on our existing network augmented with some additional research into human rights groups working in areas that were otherwise underrepresented. Though every attempt was made to approach organizations without a specific China focus, the organizations that participated in the exercise were likely those with an interest in China.

The questions sought a range of information, including:

The response rate for the survey was approximately 14 percent, comprised of 23 respondent organizations that, as a group, work on every global region. HRIC did not participate in the survey.

Several points regarding the geographic region attributed to the respondents are important to highlight. The groups were asked to indicate the country or region that their human rights work focuses on, which may or may not be their country of origin. For instance, though we had responses from several organizations based in Western Europe and the United States, these groups were consistently categorized as “global” and or by the specific region(s) that their work focuses on. A second important clarification is that respondents were permitted to select multiple geographies if their organization worked on multiple regions. Consequently, some organizational responses may be counted twice when comparing regional breakdowns. Finally, in regional comparisons four broader regions emerged from the respondents: Asia, Africa, Americas and Global. Organizations that indicated a global focus were only included in the global category; however, organizations which focus on a few countries that span regions may be included in multiple broad regions.

Where specific questions require additional methodological clarification, that information is provided in the discussion accompanying the charts below.

Survey Results

The charts below and accompanying description illustrate the overall responses received for seven of the ten survey questions.1 In some cases, comparisons by broader regional groups are broken out as well.

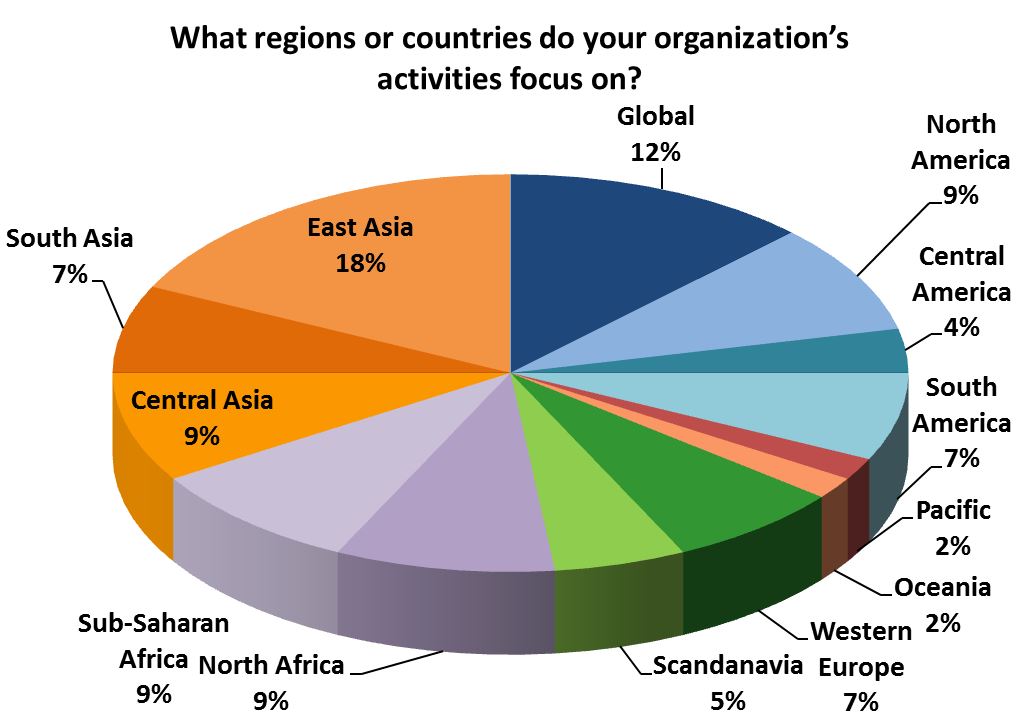

QUESTION 1: GEOGRAPHY2

Results from the first question show that respondents came from organizations working in nearly every global region. East Asia was the most represented geography, with 18 percent of the respondents working in this region, followed by organizations with a global focus, which constituted 12 percent of the responses.

In total, groups working on Asia (including East, South and Central Asia3) accounted for 34 percent of all responses. This is unsurprising given that this group was drawn from our network and is more likely to be engaged in the issue. At this broader regional level, 20 percent of the respondents focused on the Americas, 18 percent on Africa and 12 percent worldwide. Since all of the organizations which indicated a European or Pacific/Oceanic focus were also included in one of the other regional blocs, this group is not broken out for comparison in subsequent charts.

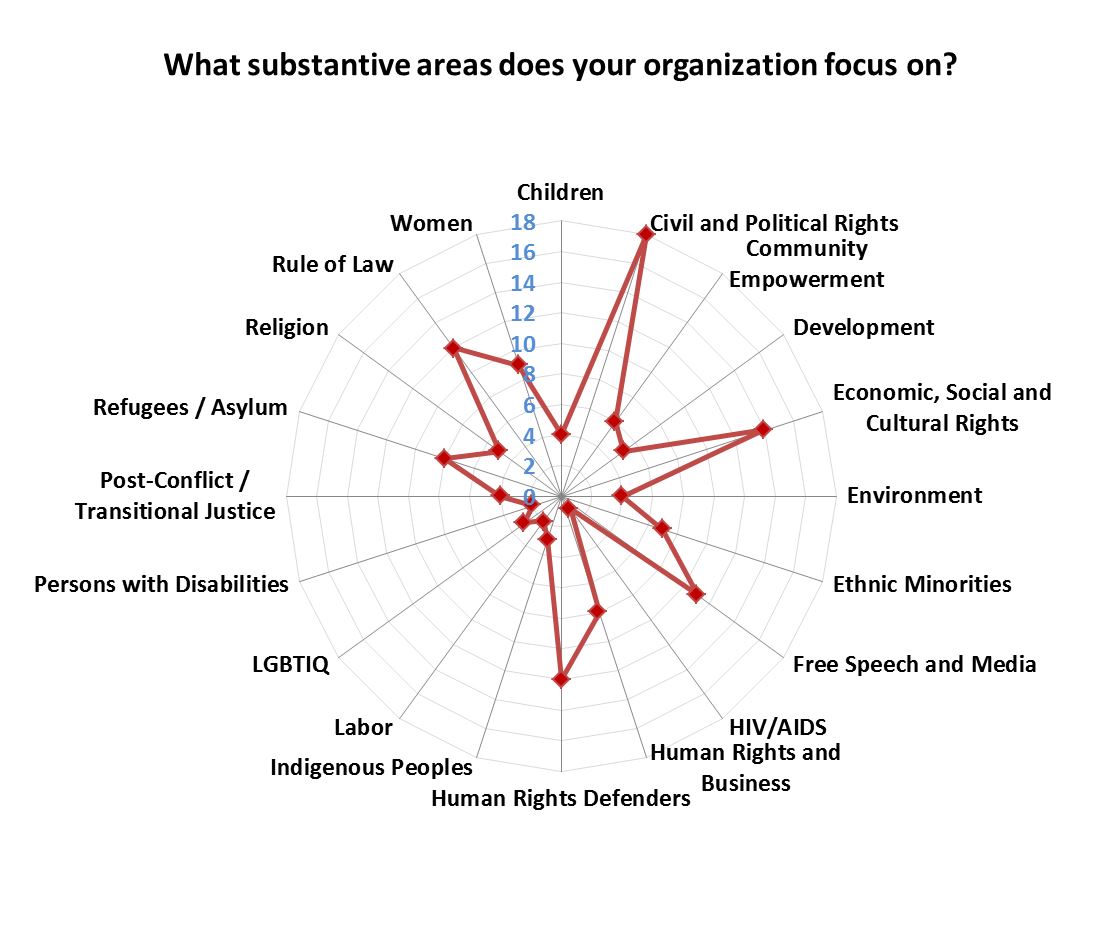

QUESTION 2: SUBSTANTIVE AREAS OF FOCUS4

The second question examined the substantive focus areas of the contributing organizations. Respondents were permitted to select as many areas as applied and, as a group, indicated a broad range of substantive work. The outer circle of the above chart reflects the most common answer, rather than the total number of respondents, with the center of the circle representing no response. In this case, civil and political rights was the most popular response with 18 of the 23 organizations indicating this area of focus. Economic, social and cultural rights and human rights defenders were the next most common focus areas, with 14 and 12 responses respectively. The least common areas were persons with disabilities, which no responding organization focused on, and HIV/AIDS which only 1 organization focused on.

The large focus on civil and political rights is interesting in light of the high number of organizations working on human rights issues in Asia. North America and both North and Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for the majority of the organizations that indicated a focus on economic, social and cultural rights.

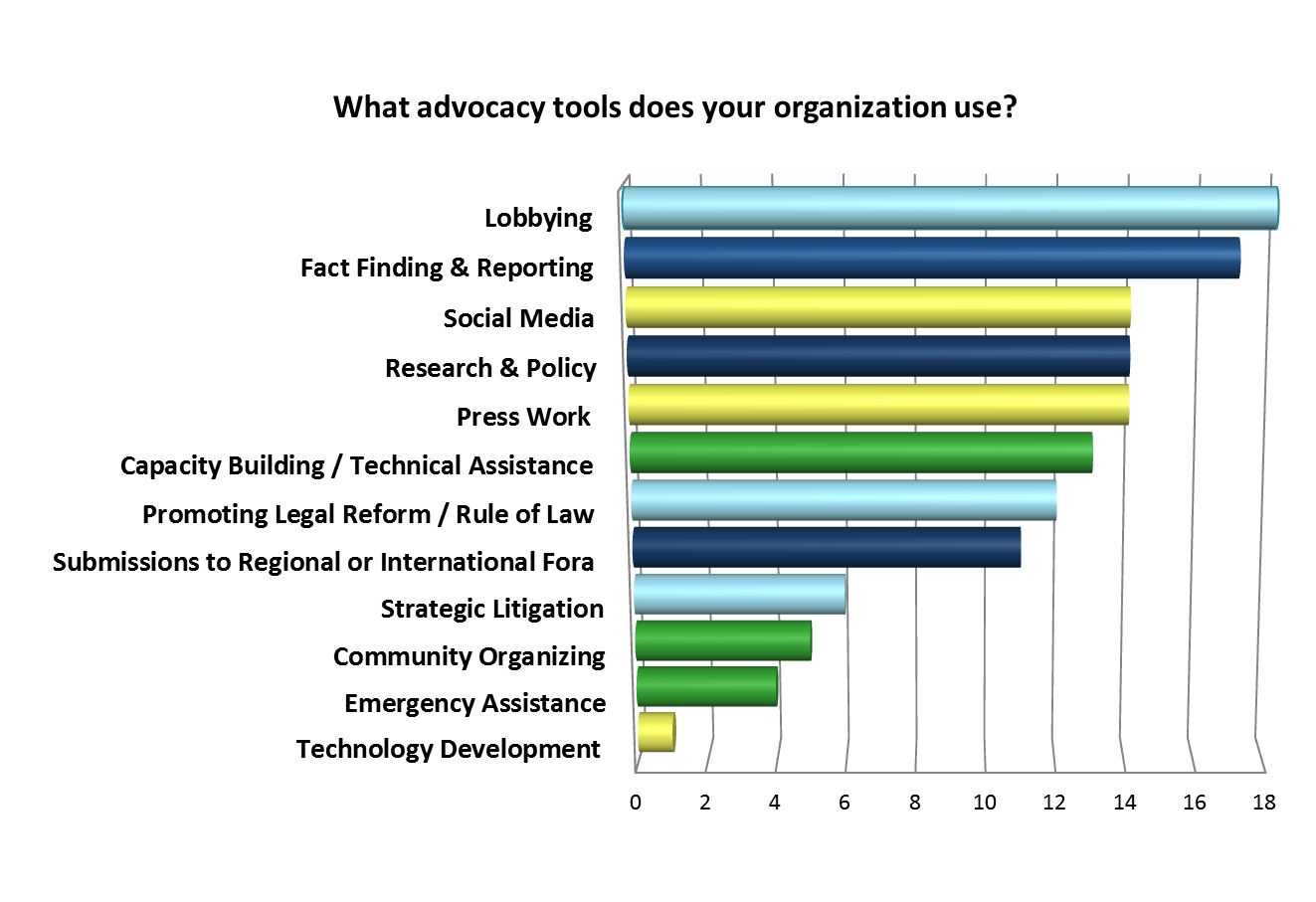

QUESTION 3: ADVOCACY TOOLS5

The third question asked respondents to indicate which advocacy tools their organizations use. Again, the survey provided a list from which to make selections and respondents were permitted to choose as many as applied. The below chart depicts the distribution of different tools.

In this chart, systemic interventions are reflected by the light blue bars, research and monitoring by dark blue, media and technology by yellow and local empowerment /support by green. This color scheme is just one of many possible groupings of similar approaches, and is not intended to be definitive, nor exclusive, but rather a heuristic lens to add dimension to the data.

In general, there was a good distribution of tools among the responding organizations, but local empowerment efforts were somewhat underrepresented. We note that, while civil society organizations are one of the key end-user groups for technology, the data suggest that CSOs are not as active in the development of new technical tools. One interesting question to pursue is whether this picture holds true more generally.

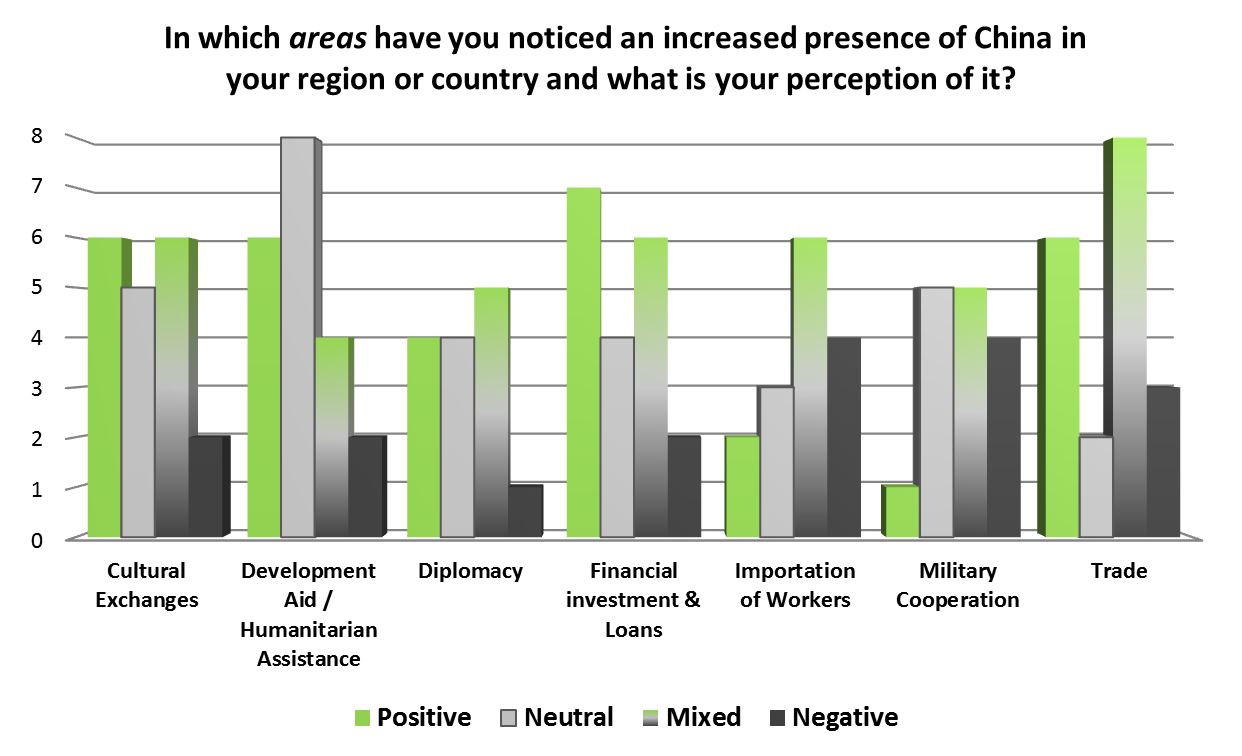

QUESTION 4: AREAS OF INCREASED PRESENCE6

The fourth question asked respondents to identify the key vehicles for China’s increased presence in the country or region they work on. They were further prompted to indicate whether they perceive this increased presence as positive, neutral, mixed or negative.

Respondents observed the greatest increase in China’s presence through: cultural exchange; financial investment and loans; and trade (each receiving 18 responses). Within these categories, 73 percent of the respondents saw the change in trade as mixed (42%) or positive (31%). Views regarding the impact of financial investment/loans and cultural exchange were more evenly distributed. The greatest consensus in responses, which was notably only eight out of twenty-three, indicated that increasing development aid was viewed neutrally and trade was viewed as a mixed development.

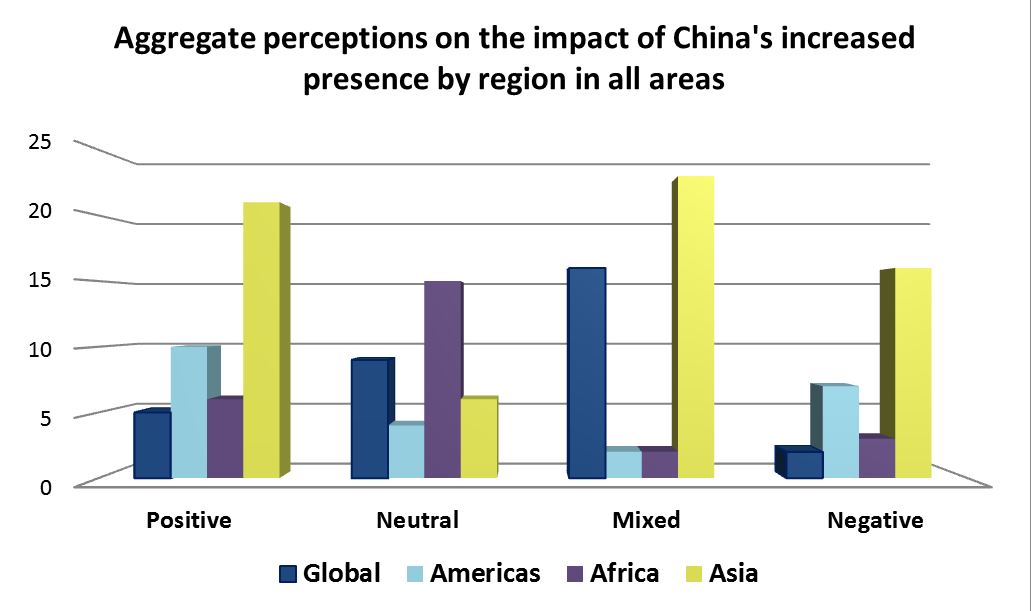

When these results are broken out further into broader regions, the impact of the larger number of respondents focused on Asia becomes clearer. The following chart compares aggregated regional perspectives on the impacts of China’s increased presence. It was generated by tallying the positive, neutral, mixed and negative responses by region and across all areas.

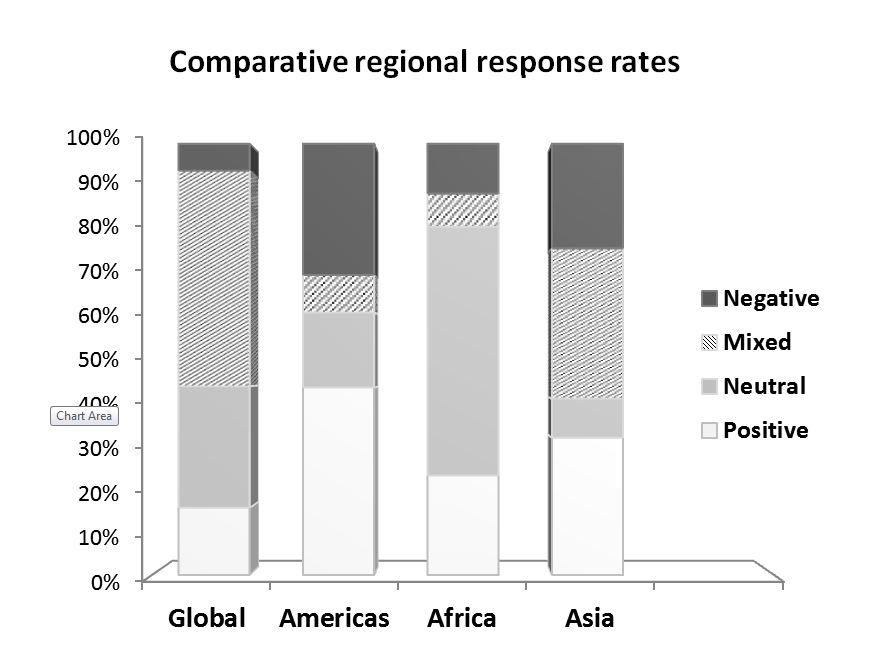

In order to address the imbalance in the number of answers between groups, the chart below examines the percentage of negative, mixed, neutral and positive responses by each region. When viewed this way, the differences between regional responses become more apparent, though the datasets become quite small and therefore any seeming ‘trends’ should not be overstated. Given the proximity to China, it is understandable that organizations working in Asia were the least likely to view the impact of China across regions as neutral (9 percent). The Americas showed the greatest polarity in opinions with both the highest negative and positive response rates (30 and 43 percent respectively). The global group was the most likely to indicate the impact of China has been mixed (50 percent), while Africa viewed the impacts predominantly as neutral (58 percent).

QUESTION 5: SECTORS OF INCREASED INVESTMENT/COLLABORATION7

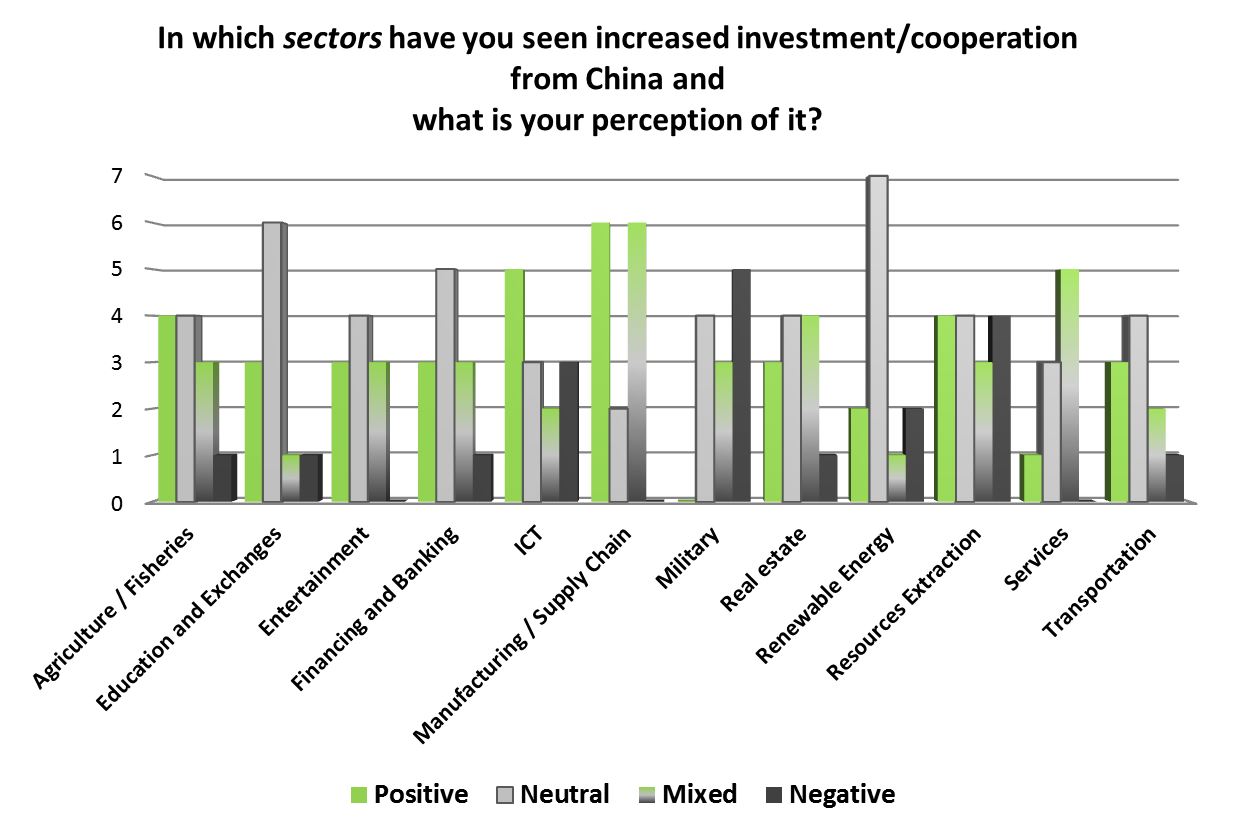

The fifth question looked at specific sectors in which respondents have observed increased investment or cooperation from China in their country or region of focus. Responses indicate that military involvement was viewed most negatively, whereas investment/collaboration in the manufacturing and supply chain sectors was viewed most favorably, followed by ICT investment. The most conflicted perspectives related to resource extraction, which received an equal number of responses indicating that impacts on this sector were positive, negative and neutral.

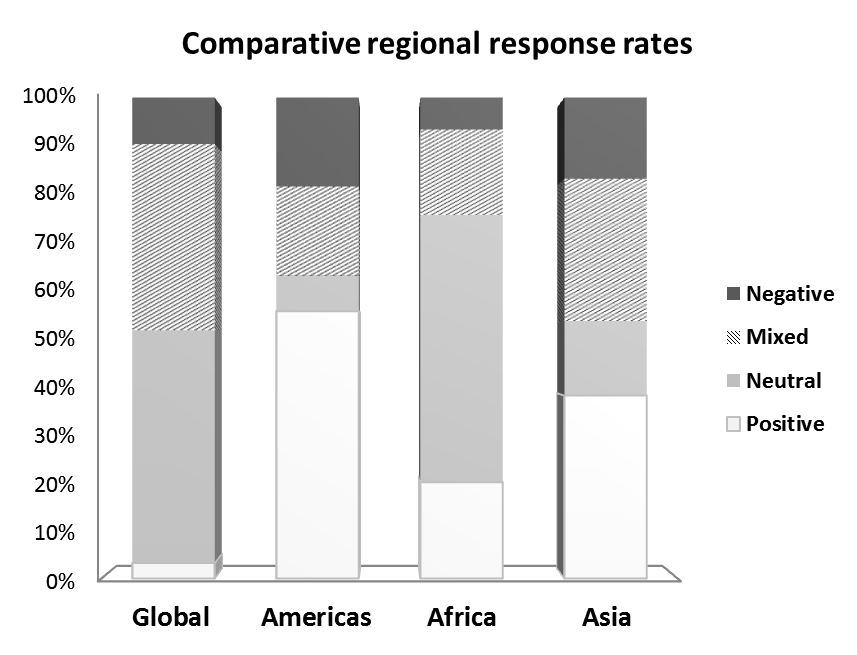

When this group of answers was broken into a broader, aggregated regional comparison, we again found the Americas to hold both the most negative (19 percent) and the most positive views (56 percent), though with a distinctly positive outlook. The global group viewed China’s investment/cooperation in the identified sectors as the least positive (1 percent), and Africa viewed China’s involvement in the region the most neutrally (56 percent).

QUESTION 6: RELATIONSHIP TO HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES8

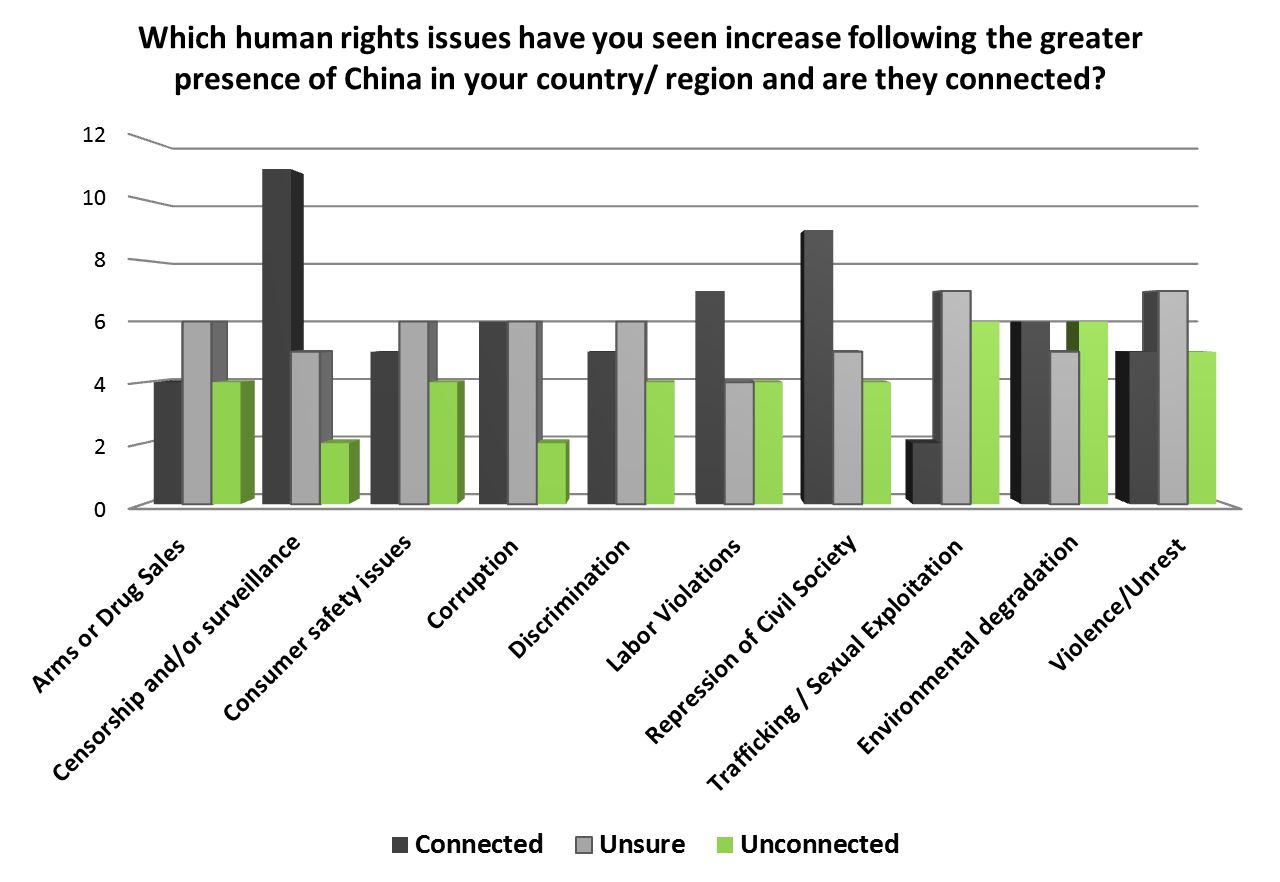

Question six asked organizations to specify which, if any, of the listed human rights issues they have seen increase following the greater presence of China in the country or region they focus on. They were further asked to indicate whether they believed these increases to be connected to China’s presence.

The greatest consensus in this section formed around the issues of censorship/surveillance and repression of civil society, which received the highest overall response rates and were the issues viewed as most connected to China’s presence.

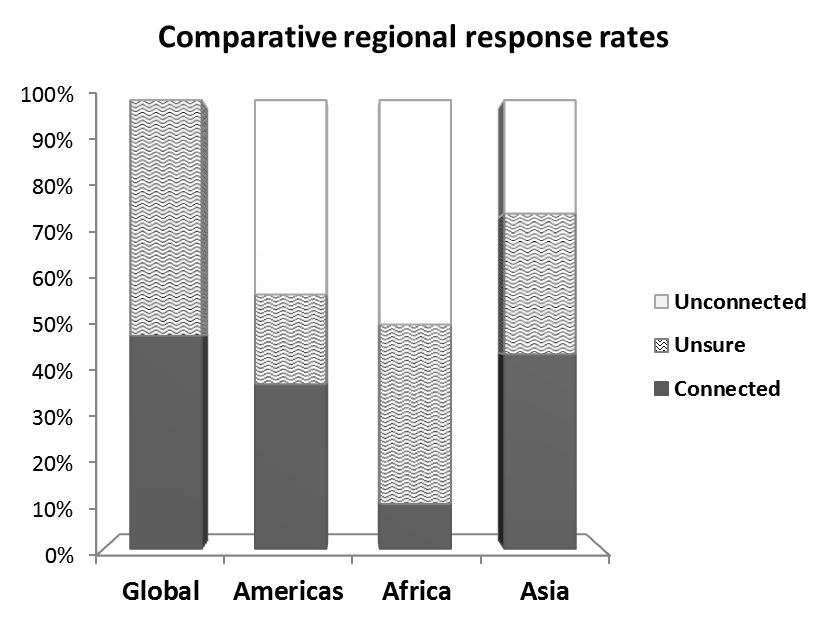

When that data are aggregated and broken into broader regions, the most striking result is that the global group viewed human rights issues as the most connected to China’s growing presence. This is evident in both the high level of “connected” responses (48 percent) and no “unconnected” responses (0 percent). The region which viewed China as most unconnected to their human rights issues was Africa (50 percent). The responses of the Americas group indicated the highest level of certainty regarding China’s connection (37 percent) or lack of connection (43 percent) to local human rights issues.

QUESTION 7: STRATEGIES OF ENGAGEMENT9

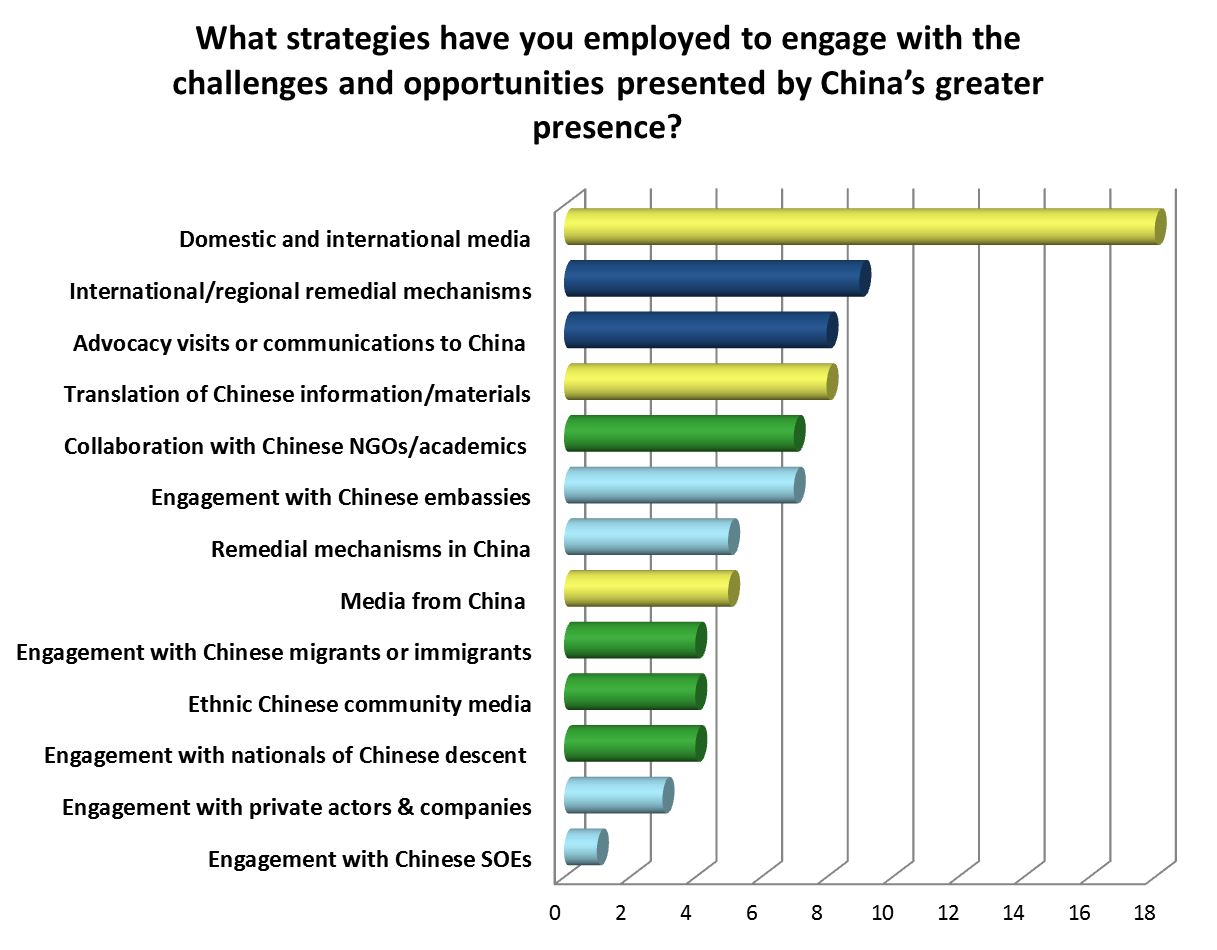

The final question sought information about the strategies that civil society is pursuing to engage with China as it becomes a more important player in local communities.

As with question 3, which examined advocacy tools, we color coded the responses by category, as a heuristic lens. The yellow bars again equate to the use of media, dark blue to international and multistakeholder engagement, light blue to strategies related to Chinese mechanisms and state/private actors or companies, and green to strategies geared toward Chinese people (both inside China and outside).

The use of domestic and international media was by far the most common approach, which was selected twice as often as the next most numerous response, international/regional remedial mechanisms. As in question 3, strategies which focus on engaging civil society were less popular. Engagement with business, especially Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and private actors, was the least common method of engagement.

1. The remaining three questions inquired about contact information, the size of the organization; and the number of volunteers or members.^

2. Total number of responses to question one: 23^

3. One organization working on Russia was included in the Central Asia cluster.^

4. Total number of responses to question two: 23^

5. Total number of responses to question three: 23^

6. Total number of responses to question four: 22^

7. Total number of responses to question five: 20^

8. Total number of responses to question six: 22^

9. Total number of responses to question seven: 23^

HRIC also took advantage of our participation in the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) 38th Congress in Istanbul, to speak with defenders working on Burma, Belarus, Cambodia, Liberia, and Mexico. Watch excerpts from our conversations below.