[Translation by Human Rights in China]

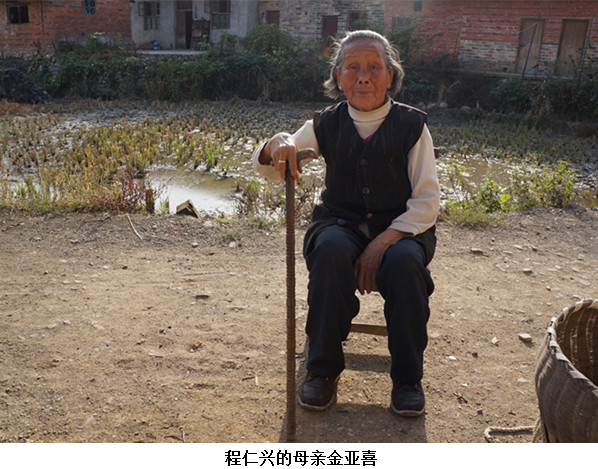

Guo Liying (郭丽英) and I returned to Wuhan, Hubei Province, after visiting a victim’s family in the city of Xiantao. We then took a bus to Tongshan County, Xianning City in Hubei to visit Mrs. Jin Yaxi (金亚喜), whose son Cheng Renxing was killed in the June Fourth massacre.

We only have an old, blurry photo of Mrs. Jin Yaxi with her children. Over the past years, we have always contacted her through her eldest son Cheng Xianren (程先任). Since he died of cancer a few years ago, we’ve kept in touch through Cheng’s wife, Mrs. Xia Xiya (夏细亚).

At the age of 86, Jin Yaxi lives deep in the mountains and rarely leaves home. She has no source of income. She had three sons and two daughters. Her husband and eldest son died of illness. Her second son was killed during June Fourth, and her youngest son has moved away from home with his whole family to work. In view of this we regard her household as one that is facing extreme hardship. Her relatives have not wanted people to visit her, concerned that talking about her son’s death would upset. It has been more than two decades. But every time someone mentions her son’s name, her tears would well up and it would take several days before she could recover from her grief.

When we, victims’ family members from Beijing, decided to visit her, I sent a text message to the son of her eldest son Cheng Xianren—who was working in Nanjing—to tell him that we planned to visit his grandmother in the near future, and hoped that the family wouldn’t oppose it. We also wanted to record her image to serve as a witness to history.

He immediately contacted his mother, Xia Xiya, asking her to go home to see his grandmother and have her mentally prepare for our upcoming visit in the hope that she wouldn’t become too upset.

It takes more than three hours by bus to get from Wuhan to Tongshan County, which is located southeast of Wuhan. An hour into our ride, we entered the mountains and drove through a forested area on the provincial highway. Tongshan County is under the jurisdiction of Xianning City. We had to go through Xianning City to reach Tongshan County, within which lies the Mufu mountain range. The highest peak of the range is more than 1,600 meters tall, the highest point in southeast Hubei Province. The mountain range makes the county’s elevation higher on the south and north sides than on the east and west sides, with multiple river basins in the center. The mountainous areas account for more than 78.6 percent of the county, which is categorized as a middle-to-low hilly region. When we reached the county seat, we could see the mountain range in the distance. It’s a small and quiet county town, with few pedestrians in the streets.

While we were in Wuhan, we called Mrs. Xia Xiya in advance. When we reached the county seat, she was already waiting for us at the bus stop. She’s not a tall woman. She was dressed in a dark green leather jacket and has a dark complexion. She’s clearly a competent and hard-working woman. She’s the only one among the generations of Jin Yaxi’s children and grandchildren to have remained home. She takes care of all family matters, both big and small, by herself.

We stored our luggage in the place we were going to stay. In the afternoon, Xia Xiya helped us hire a van for 120 yuan to take us to and from her home in the mountains. We set off from the county town and drove for more than an hour on the freeway through the center of the county. There are no mountains in that area. We bypassed the entrance into town and drove along a small road beside the town into the mountains. Most of the road is only one-lane wide. If there is an oncoming vehicle, the driver has to find a wider area to pull over to let the other car pass. Fortunately there wasn’t much traffic on the road, and we didn’t encounter this situation.

The mountains in this area are not high but quite rocky, covered with only a thin layer of soil. In addition, rainfall is not plentiful each year. Instead of tall and dense woods, there are scattered pine trees here and there. The mountains are covered with meter-tall thin grass. Because it was November, the grass had already turned yellow. The area looked poor and barren.

Our car meandered at the mid-level of the mountains, passing one mountain after another. We felt as if we would never see the end of them. There were no households that one could see, just our car driving forward. On our way, Xia Xiya told us that if she couldn’t find a car going into the mountains on her way home, she would have to walk home, which would take her three hours. Sometimes she has to walk after dark. Having grown up in the mountains, she’s gotten used to walking on the road at night and is not afraid. There are no large wild animals in the mountains. She’s heard that there are wild boars, but she’s never seen one herself.

She said that her mother-in-law, Jin Yaxi, actually grew up with her own mother as a sister. When she was little, she didn’t know that her mother-in-law and mother weren’t biological sisters. She only learned it from someone else when she was older. Her own family lived in town. Her mother was set on marrying her into this family, and told her to treat her mother-in-law as her own mother. Because Xia’s husband died prematurely, leaving her to assume all the responsibilities of the family, she couldn’t help being resentful of her mother for her decision to marry her into this family.

We drove in the mountains for more than 30 minutes before we began our descent. What we then saw was like another world. In front of us lay a freeway that came from the direction of Jiangxi Province and went who knows where. On one side is farmland. On the right side of the freeway was a large village, built against the side of the mountain. This place felt pure, far from the mortal world, where generations of people live and die by the cycles of nature. Driving upwards along the mountain foothills, we parked in an open space paved with cement. This must be the center of the village. Next to the open space was a small pond. Small village shops surrounded the open space.

Mrs. Jin Yaxi, Cheng Renxing’s mother.

Xia Xiya led us down through an alleyway. She pointed to a farmhouse on the side of the road not too far away, where an old woman sitting in a chair was picking something out of a wicker basket and peeling it. She told us that this was her mother-in-law. As we approached, Xia Xiya introduced us to her mother-in-law, Mrs. Jin Yaxi. The old woman stood up and asked us to sit down. Although advanced in age, she still looked very healthy. She was wearing a white turtleneck with a black embroidered vest over it and a pair of black pants. She looked neat and sharp. Across from the house was a small pond that was supposed to be used to grow edible lotus plants. But because it was autumn, the pond was covered with withered lotus branches and leaves. A few ducks were paddling around in the pond.

Jin Yaxi and Xia Xiya, her eldest daughter-in-law

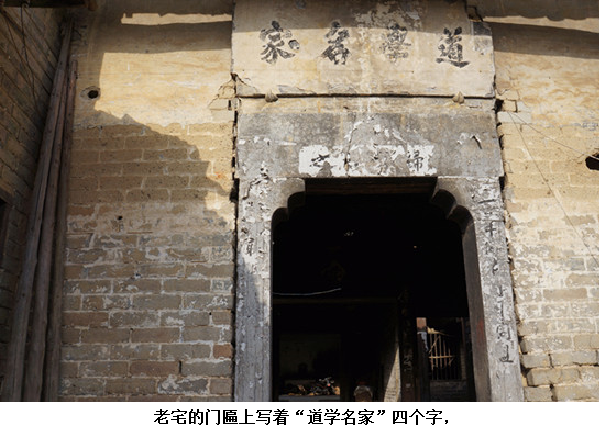

Above the door was an inscription plaque with four Chinese characters that said “Taoist Master.” Walking inside the old house, we saw separately constructed structures on both sides. The structure on the right remained standing while the one on the left was in ruins with weeds growing all over the floor. The foundation of this building belongs to Jin Yaxi’s husband, and in name it belongs to her eldest son. Further inside is a big enclosed courtyard, behind which is a two-story building. The main hall on the ground floor of the building led directly to the backyard of the old house. On both sides of the hall there were separate buildings. The entire old house was very big, although it was in pretty bad shape. One can imagine how impressive the house must have looked when it was first built. The Chengs must have been a very prominent family in this village in the old days.

The four Chinese characters on the inscription plaque read “Taoist Master”

Along the outer wall on the left side of the house is another small house, where her eldest son Cheng Xianren lived when he was alive and where Jin Yaxi still lives by herself. Jin Yaxi and her husband, Cheng Xijian, had three sons and two daughters, but only one of the sons is still alive, and two daughters are married and live outside of the village. They come to visit her often.

We asked both of them to sit down and tell us the pain and suffering brought upon the family by the death of Cheng Renxing, a graduate student at Renmin University of China. Scheduled to finish his studies that year, he was shot to death during the June Fourth massacre.

The following is a record of our conversation with Xia Xiya and Jin Yaxi.

Xia Xiya: “My mother-in-law doesn’t know the details of the situation in Beijing and doesn’t know what to say. On June 19 or 20, 1989, my mother and I were both working in the fields on the mountainside when we received a telegram from the school. The news sent our whole family into deep grieving. My in-laws cried their eyes out. A few days later, my father-in-law, husband, younger brother, older and younger sisters and their husbands went to the school in Beijing. I stayed at home to keep my mother-in-law company. I don’t know much about what they did in handling the funeral affairs in Beijing. After Cheng Renxing’s body was cremated, they brought his ashes back and buried him on the hill behind our house.

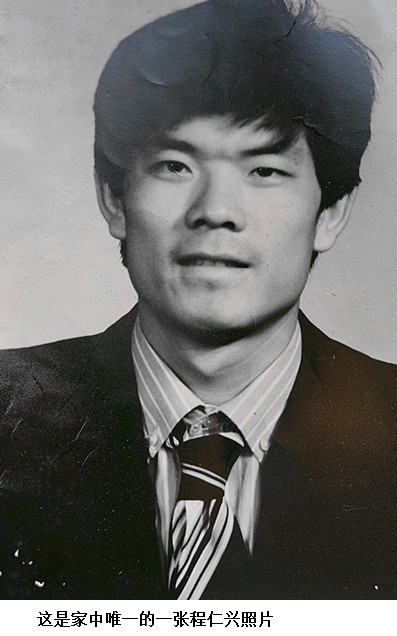

The only photograph of Cheng Renxing that the family has.

After coming back from Beijing, my father-in-law drank all day long. Every day he sat at the door like a crazy person, calling out Cheng Renxing’s name and saying that he’d come back home. But that was only in my father-in-law’s imagination—in fact, Renxing could never come home again. Eventually, he drank himself to death. If someone mentioned my younger brother’s name in front of my mother-in-law it would make her cry.

In those years, Cheng Renxing was the only one in our entire county who went to school in Beijing. What a misfortune that such a talent was shot to death.”

You Weijie: “How did you all support him to go to school?”

Xia Xiya: “My god, that was so pitiful. My father-in-law was a really smart and hard-working man. When the old sow we raised gave birth to piglets, he sold the baby pigs. My father-in-law also raised ducks. He would also sell sweet potatoes and rice as soon as they were harvested. He also grew vegetables but was always reluctant to eat them—he would sell them instead. That was how they supported Cheng Renxing’s studies.”

You Weijie: “It really wasn’t easy. On our way here, we traveled over many mountain roads. I can imagine how difficult the road to school must have been for him. Where did Cheng Renxing attend elementary school?”

Xia Xiya: “He attended elementary school in the village, and middle school in the county town. The room on the other side was his. His photo and the books he used at school are still there. You can go have a look.

“Every time he came home, our fellow villagers would come and visit him. They all felt it was so amazing that our family produced a university student. So they were solicitous. After learning that he was shot to death in Beijing, the villagers said that he was a counterrevolutionary and stopped talking to us for a long time. My mother-in-law was very worried. She didn’t dare to say anything casually.”

You Weijie: “Grandma, can tell us your thoughts?”

Choking up, Jin Yaxi said something to her daughter-in-law. Though I couldn’t understand, I knew how much pain she must feel at the death of her second son.

Xia Xiya: “She said she doesn’t know how to say it. She doesn’t know what will become of our country in the future—so she doesn’t dare say anything. I told her, at her age, it’s okay for her to say anything she’d like.”

You Weijie: “Actually, we shouldn’t have come and disturbed grandma’s life. But next year will be the 25th anniversary of June Fourth. We hope that grandma can tell us how she feels about her son being shot to death. She ought to ask for justice.”

Jin Yaxi: “My son was shot to death. I’m not willing to let it go!”

Hearing my conversation with her daughter-in-law, she began to cry. For an old lady who has spent her life in the mountains and has never left their mountain home, her son being shot to death is her greatest suffering. “Not willing to let it go”—how weighty these words are.

Guo Liying stepped forward and helped Mrs. Jin Yaxi stand up and comforted her. After she calmed down, she and her daughter-in-law led us through the open area where we parked our car on our way here, past the pond, and along another alleyway to the entrance of the house Jin Yaxi and her husband built for Cheng Renxing and their youngest son. It’s a brick house. The main hall in the middle was flanked by bedrooms on both sides. One was for their youngest son, the other for Cheng Renxing. Cheng Renxing’s room is empty, with only an old cupboard and a not-too-large table in it. From the cupboard Jin Yaxi took out a photograph of Cheng Renxing in a Western suit—the only photo the family has of him—and textbooks he used while studying at elementary and middle school.

Looking at this room and the mother in front of me, I can imagine the hardship Cheng Renxing’s parents went through in order to support him in school and to enable their three sons to get married and have children of their own. The price they paid is beyond description. I was reminded of the oil painting “Father” by the painter Luo Zhongli. I felt that no artistic rendering can more precisely express the love of this peasant couple for their children than the sun-tanned, wrinkled face with the honest and kind expression depicted in the painting. Now, the house remains but the person is gone. The only thing left to the mother is her endless longing for her son.

We accompanied Jin Yaxi back to her living quarters. Xia Xiya took us to the back hill where Cheng Renxing is buried. We passed two small vegetable plots and walked uphill on a narrow path. On the slope in the middle of the hill stood a few stone tablets. Cheng Renxing’s tombstone was among them. The shape of the tomb is no longer visible, with a few bricks on the ground marking the grave. The tombstone was full of Chinese characters. Carved a long time ago, they’ve become blurred with age.

Xia Xiya told us that Cheng Renxing had a fiancée who was the granddaughter of his academic advisor. The advisor admired Cheng’s talent and decided to let his granddaughter marry him. The two had decided to marry after his graduation. Who would have thought that Cheng Renxing, already assigned a job in Guangzhou even before his graduation, would have his life snatched away by an evil bullet before he could leave school. His fiancée was already pregnant then. She was present when his ashes were buried. On his tombstone was inscribed: Gan Zhaohui, your wife, from the capital’s Jiaotong University. She has never come back since she left. No one knows if she gave birth to the child or not. If the child was born, he or she would be 24 years old now. This has become a secret cause of regret for his mother, who complains, from time to time, that her second son died prematurely without producing a male offspring. She hoped that someone could find the girl and ask about the child. If the child is alive, she hopes that the child would acknowledge his or her ancestors. But in the boundless ocean of people, there is nowhere to look.

According to Xia Xiya, when Cheng Renxing came home for Chinese New Year in 1989, he said to her: “These years that I’ve been attending school outside the village have made life very hard for my parents, older brother and sister-in-law, and younger brother and sisters. I’ll graduate in six months. After graduation, I will repay my parents, and you all won’t have to work so hard anymore to support me. You’ll be able to relax and rest.” When Xia Xiya thought of this, she felt sad. She didn’t know that these would be his parting words.

© All Rights Reserved. For permission to reprint articles, please send requests to: [email protected].

You Weijie (尤维洁) and Guo Liying (郭丽英) are members of the Tiananmen Mothers.

Cheng Renxing (程仁兴), 25, graduate student at the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe Research Institute of Renmin University of China. He had graduated from Central China Teachers’ College in Wuhan as an English language major. In the early morning of June 4, 1989, beneath the national flag at Tiananmen Square, he was shot in the abdomen. He was taken to Beijing People’s Hospital in northwest Beijing, where he died. This is the first victim documented by the Tiananmen Mothers who was killed in Tiananmen Square.

Cheng Renxing (程仁兴), 25, graduate student at the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe Research Institute of Renmin University of China. He had graduated from Central China Teachers’ College in Wuhan as an English language major. In the early morning of June 4, 1989, beneath the national flag at Tiananmen Square, he was shot in the abdomen. He was taken to Beijing People’s Hospital in northwest Beijing, where he died. This is the first victim documented by the Tiananmen Mothers who was killed in Tiananmen Square.

Previously Issued