[Translation by Human Rights in China]

This is a moving story. The searching for Chen Yongting’s family touched the hearts of many people. This is also a sad story: behind this peasant boy from a remote mountain village going to school in Beijing was the heavy burden of his impoverished parents and brothers and their support. Whoever saw the situation of his family couldn’t help shedding tears.

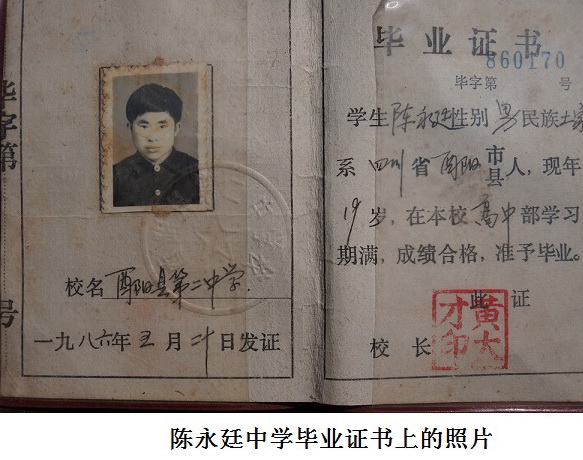

Chen Yongting’s photo on his high school diploma.

In 2008 or 2009, Mr. Chen Yunfei[1] from Chengdu, Sichuan Province, sent photos of Chen Yongting’s student ID and his grave to Ms. Zhang Xianling.[2] Ms. Zhang then gave them to Ms. Ding Zilin.[3] This name was then recorded in our list of victims as number 202. All we know from his ID is that he was a student at the Central Institute for Nationalities, a native of Youyang County of Chongqing, and of the Tujia ethnic minority. Nothing else. His family is among those outside of Beijing that we wanted to visit.

To do this we needed to first locate Chen Yunfei to get information from him. We had never contacted him before. All we knew was that he sympathized with the families of June Fourth victims and once ran an ad in the Chengdu Evening News that said: “Salute the Tiananmen Mothers.”

……

Before going to Chengdu, I called and got through to him.

Chen told me: “I wasn’t the one who found Chen Yongting’s family. It was someone from Youyang. He spent three years before finally tracking them down.”

“Do you know each other? Could you help us ask how we can get to Chen Yongting’s house?”

“We didn’t know each other previously. I reached hold of him after seeing the photo of Chen Yongting’s grave that he posted online in 2008. He is a very good person. In 1994 he started to financially support Chen Yongting’s parents. He said he doesn’t have time during the day but can go to see you at your hotel in the evening”.

At about 9 p.m., Chen Yunfei came to our hotel with his friend. His family name is Zhang, a graduate of Zhejiang Survey Engineering Institute and a native of the old Longtan Township in Youyang County. In 1989 he was working as a reporter for a newspaper under the Ministry of Land and Natural Resources in Beijing. Now he runs a media company in Chengdu. He is a Christian and a member of a house church.

Mr. Zhang said: “It looks like I need to accompany you to Youyang.”

He sounded definitive. As we were not familiar with the geography, we could only follow his lead.

“Chen Yunfei told me that your search for Chen Yongting’s family was quite difficult,” I said.

“I was in prison in 1989.”

“In Beijing?”

“No, I was locked up in a prison in Youyang County, my hometown. After June Fourth, many schoolmates gradually returned to their hometowns. Ours is located along the Wujiang River. To go home, we had to go up the Yangtze and Wujiang Rivers. On the ship, many people asked about the student movement in Beijing. At the beginning, we explained to them individually. Later, when we saw so many people were asking questions, we decided to make speeches from the broadcasting stage using a loudspeaker. There was a visitors’ book on the ship, some of us left remarks satirizing Deng Xiaoping, Li Peng, and others. That book later became evidence of our crimes. More than 30 students were later arrested in Youyang. Very unusual—especially for a poverty-stricken county.”

“When I was in prison, I met a student from the Central Institute of Nationalities. He told me that a Chen Yongting from his school was shot to death.”

From that moment on, Mr. Zhang began to think of looking for Chen Yongting’s family.

He said, “I remember one Mid-Autumn Festival day, I felt very sad as I stood in front of the metal-barred window, looking outside. On the following day, we were released. We were not allowed to go home, but were deported out of Youyang County. We then started searching for Chen Yongting’s family.”

Mr. Zhang continued, “It was truly difficult to find Chen Yongting’s family. Where they live is really too remote—you can say it’s in the most remote part of Youyang County. I wrote to my classmates and friends, asking them for help in finding them. I went back there once a year. I also sent a dozen or so letters. For a long time, we got no answers. It was not until the third year that a teacher from Sichuan’s Qianjiang City Teachers’ Preparatory School, who had tried all kinds of ways, finally found Chen’s cousin—a postman in Tushixiang in Youyang County. Even that cousin couldn’t see the family right away because they came down from the mountain only once every couple of months to do shopping for daily necessities, and they would visit the cousin. This was how we got in touch with the family and started giving financial assistance to Chen Yongting’s parents until they passed away.”

“When did you start giving them assistance?”

Chen Degao, father of Chen Yongting.

“1994. At the beginning, I gave them a few hundred yuan a year. When prices rose, I increased the amount to 1,000-2,000 yuan. It was in 2008 that I stopped, after his parents passed away.”

“Chen Yunfei told me that you spent about 50,000 yuan to set up the tombstone for Chen Yongting. Is that right?”

“No. Because their family was just so poor, what I did was made a 100-Sheep Poverty Alleviation Plan. In 2001, I contacted ten friends from my hometown and suggested that each one donate 5,000 yuan to buy them 100 sheep to help them lift themselves out of poverty. At the beginning, my friends all agreed. But when it came to really doing it, no one joined.”

The reporter told us that even though his friends changed their minds and didn’t join his plan, he felt that he had to fulfill the promise he had made. He paid nearly 40,000 yuan out of his own pocket to buy 50 sheep and gave them to the family. He hoped that this could somehow comfort the soul of the deceased Chen Yongting and let his soul rest. But the pity was that the 50 sheep died later due to poor management or the local climate.

He said, “The reason I did it is that I was a participant in the events of 1989. When I was still in prison, I worried about what my parents were going to do if I were shot to death or sentenced to death. I had just started working. I had two younger sisters and one younger brother. None of them had started working yet. It was these thoughts and my life values that compelled me to do what I did.”

I asked him: “Did you help write the inscriptions on Chen Yongting’s tombstone? I saw a photo of it back in Beijing. It has the characters ‘Son of the Earth’ on it. But I couldn’t clearly see the two lines of characters on each side. Before I came here, I thought he must have been from an educated, intellectual family—that they dared write like this.”

“In 1998, Chen Yongting’s cousin wrote to me saying that Chen Yongting’s parents wanted to set up a tombstone for their son. They didn’t have much education and didn’t know how to do it. In our hometown, Chen Yongting’s death was considered a violent, or “abnormal,” death, and his burial and tombstone could not be done in the normal way. Chen Yongting’s cousin told me that the family didn’t have money and asked me if I could give them the money for putting up the tombstone. I gave them 1,500 yuan at the time, and a little more later—probably close to 2,000 yuan in all, which included the money for buying the bricks for a small wall at the grave and the tombstone. After I drafted the inscription for the tombstone, I faxed it to Chen Yongting’s cousin.”

Such is the pure and innocent heart of a college graduate who had only just started working in 1989, a participant in the student movement who was wrongfully thrown into prison. His sentiment is eternally connected with the June Fourth massacre of a quarter century earlier, which has also become the yardstick by which he acts.

When we left Chengdu, reporter Zhang came to our hotel very early in the morning to help us carry our luggage. He hired a porter with a small cart to accompany us to the train station. He didn’t have small change, and yet refused to let us pay. So he took out a bunch of 100-yuan bills and gave one to the porter. He was spotted by a thief. When he was paying for his train ticket, he realized that all the money he had on his person had been stolen. We felt very apologetic. But he said jestfully, “It doesn’t matter. God is asking me to help out all kinds of people.”

After arriving in Chongqing, he told me that Youyang is a county buried deep in the Wuling mountain range and is surrounded by mountains on all sides. It is one of the poorest counties in the country. Transportation was very backward in the past. People could only go out of Youyang by river boat. But now, the new Chongqing-Huaihua Railway and Chongqing-Hunan Highway have shortened travel time between Chongqing and Youyang from one day to four, five hours by train or on the highway. Travel has become much easier.

The main section of the railway from Chongqing to Youyang runs through tunnel after tunnel in the cliffs along the Yangtze and Wujiang Rivers. Although the river scene was beautiful, it would get swallowed up in an instant by the darkness of the tunnels.

The Youyang Station is located at Meishu Village in the Old Longtan Township. After we got off the train, we had to catch a bus in front of the station and ride for more than 20 minutes before reaching the town of Old Longtan. When we were near there, he pointed out to a section of the wall surrounding the town, and we could see a pathway shaded by trees on the other side of the wall. We saw students walking on the pathway and the corner of a school building underneath the trees. He told us that this was where he went for middle school. It was built in the era of the Republic of China. There is a very large library at the school. It is a key middle school in the area.

I stayed at Zhang’s house in Gulong Township overnight. On the following day we took a bus to Youyang. The distance between old Longtan Township and Youyang County town is more than 20 kilometers and is covered by a newly built road. The Youyang County town has acquired an air of modernity. Since it is located in a mountainous area, the climate is pleasant. It is a natural oxygen bar and is known as the cool capital of Chongqing.

At this moment, what I really cared more about was the family of Chen Yongting. Twenty-five years have passed since 1989. What kind of changes has his family been through? Will I still be able to trace the life of Chen Yongting back then?

Chen Yongting’s older brother (left), third younger brother (middle) and cousin (right).

Chen Yongting was born in a small village deep in a remote mountain town in the Tujiazu-Miaozu Autonomous County, within Youyang County, outside of Chongqing. He was an ethnic Tujia. His parents had four sons. Chen Yongting had one older brother and two younger brothers. His father, Chen Degao, made a living by making wooden pails for storing grain. His mother, Zhang Bixiang, worked as a farmer. When their first son was born, the father, a simple farmer who worked and rested in the mountains and who still had a feudal mindset, used these characters in their names: Chao (dynasty), Ting (court), Bang (state) and Ding (stability), and named them Yongchao, Yongting, Yongbang, and Yongding, hoping that their sons would have stable lives.

“It is the greatest mockery,” said reporter Zhang. “Chen Yongting’s father never thought that the new government he trusted so much would send soldiers to kill his innocent 20-year-old son in Tiananmen Square.”

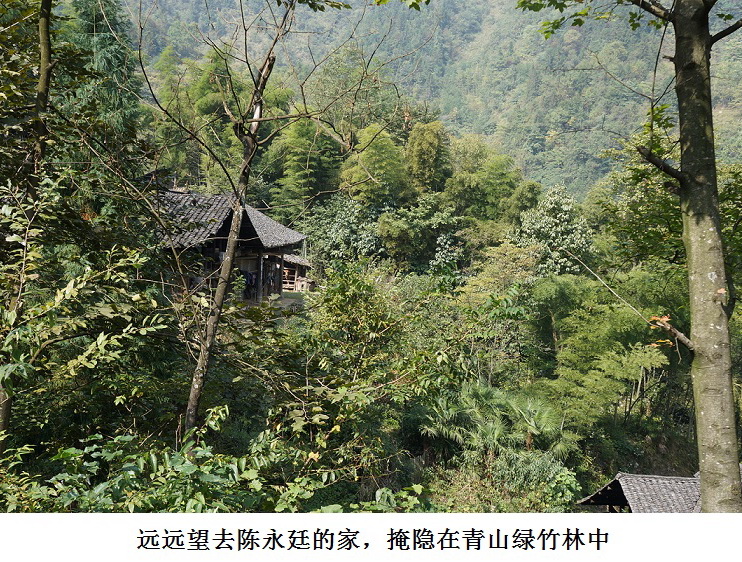

Tushixiang, where Chen Yongting’s family is located can only be reached via a narrow road built into the mountains.

We went there by a taxi Zhang had hired. The road was very bumpy. It took nearly an hour to get to Tushixiang.

In town, we met Chen Yongting’s cousin and older brother, Chen Yongchao. Chen’s older brother is not an articulate man. His cousin, the postman, who meets more people, is more talkative. He lives in town in Tushixiang and welcomed us warmly. After we rested for a little bit, the cousin found a car and, together with Chen Yongchao, took us to the foot of the mountain.

After a 30-minute drive, we arrived at the foothills. There was no road any more. Chen Yongting’s cousin and older brother led us walking uphill on a small path. The mountains here are not that high, but they go on one after another. Without someone leading the way, one can really get lost in there.

Chen Yongting’s family house hidden in a green bamboo forest.

After coming over a mountaintop, the view opened up. It’s flat land between two mountains. On one side of the road are rice paddies, on the other, overgrown barren land. I asked Chen Yongting’s brother why that was so.

He told me that many young people from the mountains have gone to work in cities. There is no one working the fields anymore, and so the land is neglected.

After walking across the flat land, we climbed uphill again. On the way, the cousin told me bits and pieces about Chen Yongting’s life when he lived at home.

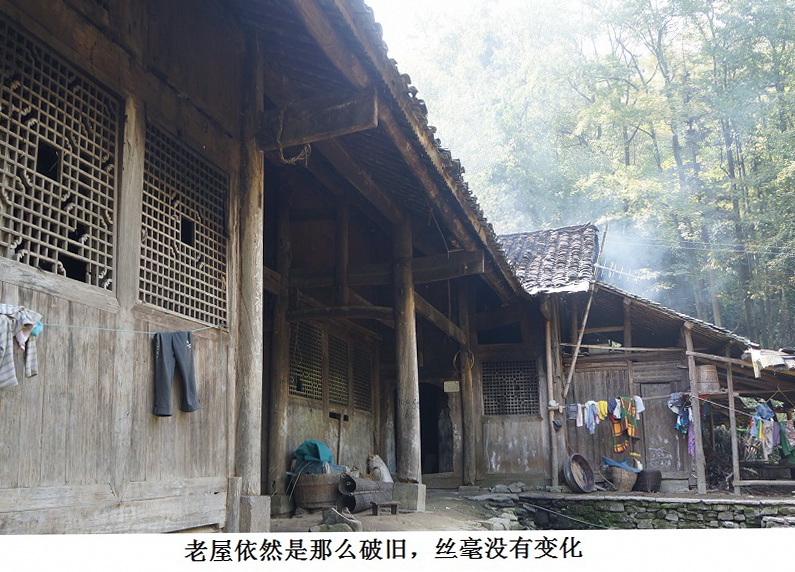

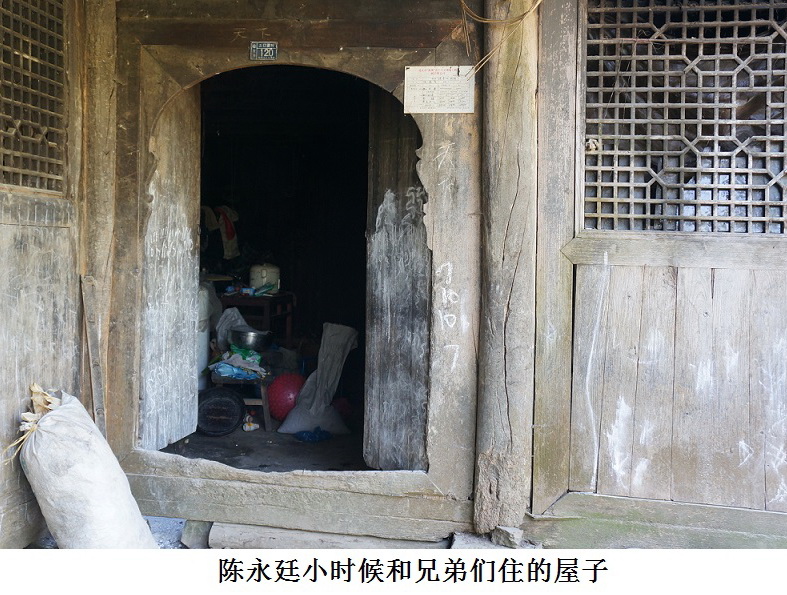

The old house still looks old and shabby. Nothing has changed.

Chen Yongting liked to read since he was very young. His brothers are not educated—he was the only educated one in his family. Because not every village had an elementary school, several villages had to share one. In order to go to school, Chen Yongting had to walk a long way in the mountains every day. For junior and senior middle school, he was admitted by Youyang County No. 2 Middle School, where he boarded. He had excellent scores and received the title of honorary student every year.

In 1986, when Chen Yongting was admitted to the Central Institute of Nationalities in Beijing—he was the first and only college student in the history of this mountain village. All the villagers were happy for him. This made his father proud. But his father needed to work twice as hard to barely support him going to school.

We walked into Chen Yongting’s home, which is hidden in a green bamboo forest. The old house still looks old and shabby.

In the house lives the family of Chen Yongting’s third younger brother. Mentally handicapped, he has the worst life skills of all the brothers in the family. He has three daughters, the oldest is about 15 years old and the youngest 6. The only one going to school is his second daughter, who is 11.

The family of Chen Yongting’s third younger brother.

The old house is made of wooden panels. Wind seeps through from all sides. There is no wardrobe in the house that can store clothes. All the clothes are hung on a string outside of the house. The living area has two rooms. This was where Chen Yongting and his brothers lived. The inner room is where they slept. There is only one bed. Things are scattered here and there. Miscellaneous stuff and cooking utensils are stacked in the outer room. Next to the living area is a central room, which has no door or any decent furniture.

“Chen Yongting’s father supported the family by making this kind of wooden pail,” said Chen Yongting’s cousin, pointing at a wooden pail standing at the door.

I asked Chen Yongting’s older brother, younger brother, and cousin to sit down for the interview.

“I’d like to ask when Chen Yongting was admitted to college.”

Chen Yongting’s father made a living by making wooden pails.

“I don’t remember exactly when. He was admitted to Youyang No. 2 Middle School in 1982, but didn’t finish.”

“It should be in 1986. He was a junior in 1989 and was about to begin his senior year,” I added, seeing their hesitation.

I asked, “Did Chen Yongting die in Tiananmen Square or outside of the square? At that time, gunshots were fired in many places.”

Answer: “It should be in Tiananmen Square. We heard that Chen Yongting was in a dialogue with Li Peng, who said that he was quite articulate but so disobedient. That’s what we heard.”

“The night before we received the telegrams, we didn’t know why but it felt as if his spirit had already come back. No one could sleep. We felt that something was going to happen.”

The house where Chen Yongting and his brothers lived together.

Question: “After you received the telegrams, did your father go alone? Did anyone go with him?”

Answer: “We didn’t go with him. He went alone. One man from our village worked in Beijing. He went with him.”

Question: “Did your father tell you how the school handled Chen Yongting’s matter?”

Answer: “He said a little. The school had someone accompany my father back. Many people at the school went to him and talked with him a lot, asking him not to worry and telling him they supported him and would avenge this for him.”

Question: “Your brother was killed for no reason. You can put your names on this signature list and ask for justice from the government for your brother.”

Answer: “We can sign. But we are not educated. We live in the mountains. That’s all we can do. You will have to do everything.”

“You can tell me stories of Chen Yongting when he was little.”

“Chen Yongting was a very simple and humble person. He was never arrogant. In those days, he would visit every family every time he returned from middle school or college. He also visited his teachers. He was a good student,” his cousin said.

The cousin and brothers also told me the following.

During Chinese New Year in 1989 when he came home, he talked about China’s economy with his cousin and brothers. He said that China’s economic policy did not comply with economic regulations and that the Party’s interest played a decisive role. He said that common folks had no say in policymaking, and that would definitely lead to corruption. In April 1989, after the death of Hu Yaobang, he participated in the student movement. He was one of the representatives in the students’ dialogue with Li Peng. On the night of June 3, he was shot dead in Tiananmen Square.

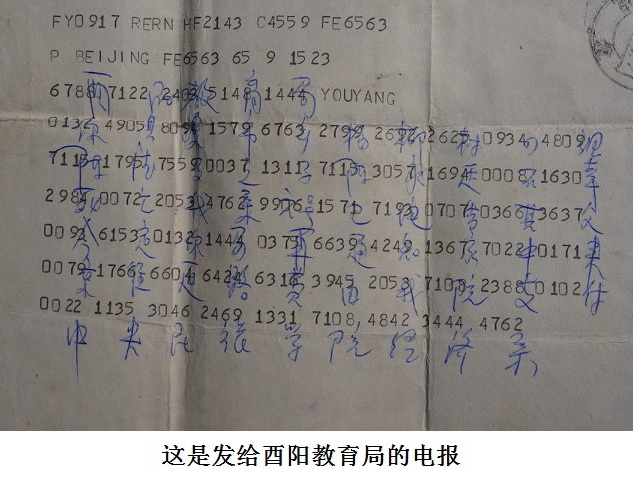

They received two telegrams from the school. The first one read: “Beijing, Chen Degao of Group 4, Yangliu Village, Tushixiang, Chen Yongting had an unfortunate death. Could you come to Beijing? Please telegraph to the Economics Department of the Central Institute for Nationalities.”

The second telegram read: “Youyang Education Bureau: Chen Yongting, son of Chen Degao of Group 4, Yangliu Village, Tushixiang, had an unfortunate death. This department telegraphed his family on June 6. We decided that you should notify his family again. His family’s travel expenses will be paid for by this institute. Department of Economics, Central Institute for Nationalities.”

Telegram sent to the Youyang Education Bureau.

Upon receiving the telegrams, Chen Yongting’s father went to Beijing accompanied by a fellow villager who worked in Beijing. The local government wrote them a letter: “To all concerned work units: Two comrades, Li Fuyi and Chen Degao, are traveling to the Central Institute for Nationalities to see their wrongfully killed son (a student, Chen Yongting). (Note: these two comrades have not been issued resident ID cards). Please provide assistance in transportation and food on the way. June 11, 1989.”

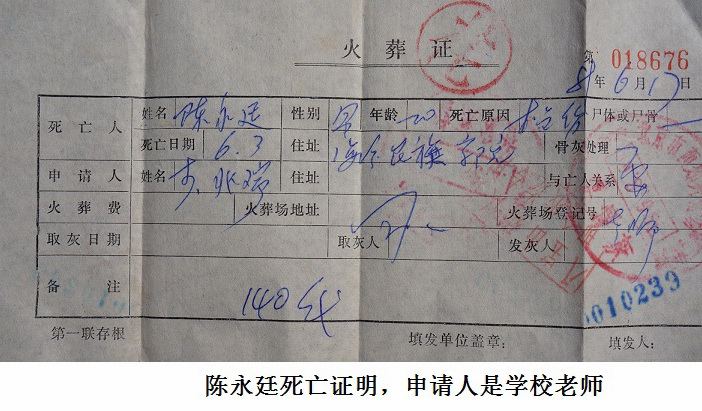

Chen Yongting was cremated on June 17. He was 20 years old. The applicant on the cremation certificate was his teacher.

After Chen Yongting’s father finished dealing with his funeral, the school set someone to accompany his father home. In those days, Chen Yongting’s school officials, teachers, and schoolmates were all very sympathetic to his death. They talked to his father and said a lot to comfort him. Because his father has died, we have no way of knowing what exactly he and the people from the school talked about and the specifics of Chen’s funeral.

Chen Yongting’s Cremation Certificate. The applicant was his school teacher.

His innocent son was shot to death. It is no longer possible to hear from his parents how they managed to carry on day after day, night after night in all those years. His mother missed her son so much that she cried every day. She went blind when she was only a little more than 60 years old, after developing serious cataracts. She passed away in 2004, at age 66. Her sons did not know the cause of her death but guessed that it was probably heart disease. She had no money to see a doctor, and could only let nature take its course. When she was alive, she didn't want to spend money to have a picture taken, so she left no photo of herself. In early 2008, his father died after coughing up blood of unknown cause. He was 76.

This pair of simple peasants lived out their entire lives in the mountains. What bitter hardships they must have endured to raise their four sons. In particular, how very difficult it must have been for them to nurture and turn out an outstanding college student! If Chen Yongting had not died and if he were accomplished in his studies, he would definitely not have let his parents’ illnesses go untreated for lack of money, and their death would not have been so sad and miserable. This is the debt owed to this family by a knife-wielding government.

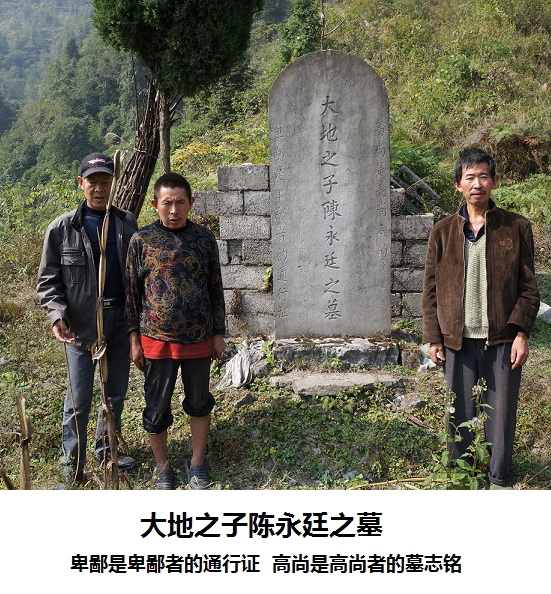

Grave of Chen Yongting. The inscription in the middle reads: “Tomb of Chen Yongting, Son of the Earth.” The couplet down the sides of the tombstone reads: “Contempt is the passport of the contemptible, nobleness is the epitaph of the noble.”

Along a narrow pathway, we climbed to another mountaintop. It was a small piece of flat land surrounded by pine trees. In the center of the flat land is Chen Yongting’s grave. Next to it is a cypress. The tombstone stands in front of a low wall made of bricks. The inscription in the middle reads: “Tomb of Chen Yongting, Son of the Earth.” The couplet down the sides of the tombstone is from two lines of a poem entitled “Reply” by the famous contemporary poet Bei Dao: “Contempt is the passport of the contemptible, nobleness is the epitaph of the noble.” When the local villagers saw the inscription, they all said that it looked like the students did not accept what happened. Indeed, with his young life and his red blood, Chen Yongting embraces the mountains, rivers, and earth of China. He will forever keep watch for the land that gave him life, raised him, and instilled in him a sense of justice, strength, and integrity. Justice has not been done. How could the students accept what happened!

Standing silently in front of Chen Yongting’s tomb, I bowed three times according to the Chinese custom to pay my respects. Chen Yongting, may you rest in peace. On behalf of all the Tiananmen Mothers, I’m standing here to express our grief. Your young life will not have been sacrificed in vain. We will work together with your brothers and ask the state for justice and dignity for you, your dead parents, and all victims killed during June Fourth. History will never forget you.

Translator’s notes

© All Rights Reserved. For permission to reprint articles, please send requests to: [email protected].

You Weijie (尤维洁) is member of the Tiananmen Mothers.

Chen Yongting (陈永廷), 20, male, a student in the Economics Department of the Central Institute for Nationalities (中央民族学院). Shot to death in Tiananmen Square, night of June 3, 1989. He was the first and only student in the history of his poor, remote mountain village in Tushixiang (涂市乡), Youyang Tujiazu-Miaozu Autonomous County outside of Chongqing, to go to college.

Previously Issued