[Translation by Human Rights in China]

In the 1970s, an article in Undergrad—a periodical published by the Student Council of the University of Hong Kong (HKU)—resonated with many people with its description of Hong Kong as a “free yet undemocratic” city. Although people argued over whether Hong Kong was truly democratic, no one had ever disputed that there was freedom in the then-British colony. Thus, the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984, reached through negotiation between the governments of Britain and China concerning the future of Hong Kong, states that Hong Kong’s way of life would remain unchanged, providing a detailed list of freedoms to be “protected in accordance with the law.” After Britain returned Hong Kong’s sovereignty to China, these freedoms are protected under Chapter Three of the Basic Law of Hong Kong, known commonly as the “mini-constitution.”

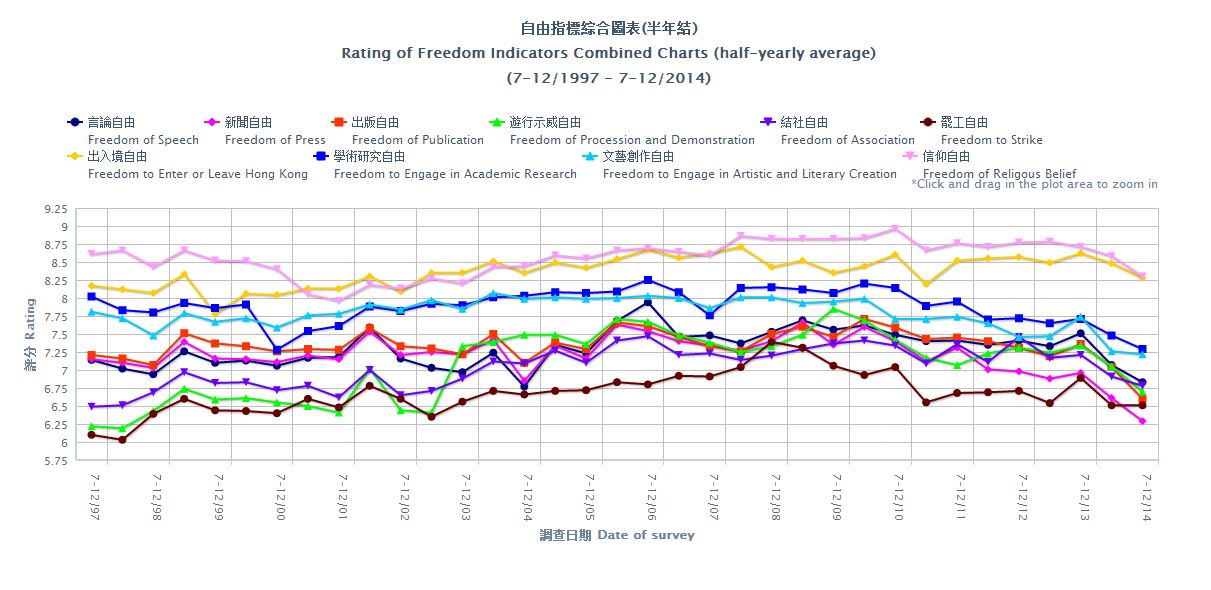

In the initial five or six years following Hong Kong’s handover to China in 1997, the Chinese government did not appear to have infringed upon the freedoms of Hong Kongers, who in turn registered their satisfaction in the periodic public opinion polls administrated by the HKU Public Opinion Program.[1] With 10 being the highest, the ratings for the various freedoms identified in the polls always ranged between 6.78 and 7.65, mostly above 7, a fairly acceptable range. Among them, freedom of religious belief received the highest satisfaction rating, normally at 8 or above since the handover. That the practice of Falun Gong, branded as a cult by the Chinese government, is allowed in Hong Kong can attest to the valid basis of this perception.

The next highest satisfaction ratings were for the freedom of entry and exit and the freedom to engage in academic research, followed by those for freedom to engage in artistic and literary creation, freedom of procession and demonstration, freedom of publication, freedom of association, freedom of the press, and freedom of speech. These freedoms scored between 6.5 and 7.9. The lowest satisfaction scores went to freedom to strike, which hovered between 6.03 and 7.39, barely making it to 7 most of the time. The reason was that protection of labor rights in Hong Kong is far from adequate. How can salaried men negotiate wages with their employers if collective bargaining is unavailable? How can the right to strike not be reduced to a mere afterthought?

Courtesy of the Public Opinion Programme,

The University of Hong Kong.

(Click to view full chart.)

The gap between reality and perception

Frankly speaking, perceived satisfaction may not correspond to reality. The discrepancy between perception and reality becomes even clearer where appraisals of freedom require professional expertise. Take the freedom to engage in academic research for example. Without scholars exposing academic repression, how many people in the general public would have known that many research topics were abandoned because they were politically unacceptable? It is only after such exposés by the professionals involved would the ordinary citizens realize that those freedoms have been infringed upon. For instance, in July 2000, then Director of the Public Opinion Program Robert Chung revealed in an article that Tung Chee-hwa, then Hong Kong Chief Executive and HKU Chancellor, had pressured him—via the president and vice president of the university—to discontinue all public opinion polls regarding the Chief Executive and the Hong Kong government. That revelation was a wakeup call to the general republic, and led to a drop of the satisfaction rate for the freedom to engage in academic research to a historical low of 7.28 that year.

The same is true with freedom of the press. If the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA) had not brought to light the severity of self-censorship over the years, how would the general public have learned that behind the enormous volume of publications out there, 30-40% of journalists have quietly deleted news items or trashed their colleagues’ reports out of concern of sensitivity and that several scholars who are perceived to be liberals have been blacklisted for interviews by some media outlets?

The question one should be asking is: when the fourth estate of a society—outside of the executive, legislative, and judicial realms—curbs itself and fails to fulfill its responsibility to expose injustice, would it leave the general public unaware of the infringements of freedoms that they should be concerned about? Would it desensitize them to the point where they don’t even know that their freedoms are being eroded?

The HKJA’s 2013 annual report on freedom of expression already pointed out that the Chinese authorities had decided in late 2003, in reaction to the Hong Kong legislature’s shelving that year of the National Security (Legislative Provisions) Bill—for the implementation of Article 23 of Hong Kong Basic Law[2]—to intensify their interference of Hong Kong affairs, establish a second power center, and reel in the media outlets they suspected of having fanned anti-Article 23 sentiments in order to gain control over public opinion. It can be felt in the press circle that, with the intensified actions by Chinese officials stationed in Hong Kong since 2004 combined with the absorption of more than half of the media owners and senior executives to the Chinese side, self-censorship among journalists has been worsening. There has been an evident decrease in coverage of topics deemed taboo by the Chinese authorities. Besides long existing sensitive issues such as pro-independence movements in Tibet, Xinjiang, and Taiwan, the media have also been quiet on the meddling in or public criticism of Hong Kong affairs by Chinese officials.

Examples of this trend abound. In 2007, the central government in Beijing, which runs a planned economy, incorporated Hong Kong’s capitalist economy into its Eleventh Five-Year Plan and barely stirred in-depth discussion in the Hong Kong media. If a matter like this—which involves a fundamental change in the defining characteristic of society—was mostly left untouched, no wonder the media only uttered cursory commentaries on how Hong Kong might be affected by the recent planning of Qianhai Economic Zone[3] and establishment of the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone. Furthermore, at the end of 2011, then publicity director of the central government’s liaison office in Hong Kong Hao Tiechuan—claiming to be writing “in a scholarly capacity”— hurled a string of criticism at Robert Chung’s public opinion survey, which showed that the number of people identifying themselves as citizens of Hong Kong had reached a ten-year high, while only 16.6 percent of those polled considered themselves as Chinese. Only two or three media outlets reported on the story; there were even fewer commentaries. Unsurprisingly, the incident made hardly any waves in Hong Kong.

Finally, the HKU poll showed a 7.7 rating for the freedom to engage in academic research in February 2012, a slight 0.2% drop from six months earlier. Does the result indicate a weakened public perception of Hong Kong’s academic freedom, or a lack of understanding thereof due to the media’s inattentiveness? This is a question worth pondering.

Mid-2013: a watershed in the shrinking of freedom

Another example is freedom of entry and exit, traditionally a point of pride for Hong Kongers. But in fact, overseas democracy activists are frequently denied entry before anniversaries of the June 4 crackdown on the 1989 Democracy Movement in China; key members of Falun Gong from overseas are mostly banned from entering Hong Kong; some pan-democratic camp representatives who are politically incompatible with the Chinese government are not allowed to return to the Mainland due to confiscated or invalidated Home Return Permits. What’s more worrisome is the escalation of the situation: in 2014, Taiwan scholar Tseng Chien-yuan was denied entry to Hong Kong in late May, and Taiwan student movement leader Chen Wei-ting’s visa application was turned down in the second half of June.

In fact, in addition to the freedom of entry and exit, other freedoms—freedom of the press, freedom of speech, freedom of demonstration and assembly, and freedom to strike—are also deteriorating. More alarming, the ratings of the ten freedoms in the HKU poll took a collective nosedive in the second half of 2013, a reflection of the fact that the curtailing of these freedoms has reached a degree of general awareness. Among them, satisfaction ratings for freedom of the press, freedom of publication, and freedom to engage in artistic and literary creation hit all-time lows since the handover, at 6.61, 7.04, and 7.26, respectively.

As for the first Hong Kong Press Freedom Index produced by HKJA, issued in April 2014, the score was low to start with. With 100 being the highest, the rating by the general public was 49.9, while that by journalists was 42—both clearly failing scores. Self-censorship was identified as the most serious problem among journalists.

Why do Hong Kongers feel that the freedoms they previously enjoyed started to shrink across the board in the second half of 2013? Unable to provide a scientific explanation, the author observes the following: Beijing’s Hong Kong policy has shifted from laissez faire to “playing the fullest role”; the central government has established a second power center with its Hong Kong-based officials; the Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying is weak [on defending Hong Kong’s autonomy]; official accountability tilts toward Beijing rather than Hong Kong citizens. One only needs to look at Hong Kong officials’ frequent summons to Beijing for policy consultation or the flaws in the simplified-to-traditional Chinese text transferring software issued by the Hong Kong Education Bureau to sense these developments. When a “free” Hong Kong takes the lead from a Beijing that prioritizes control and stability maintenance, how can Hong Kong prevent its freedom from being curtailed? Now the situation has reached a point where it can no longer be ignored. The white paper recently issued by the Chinese authorities, The Practice of the “One Country, Two Systems” Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, is but a declaration of the official abandonment of the “one country, two systems” policy that has already changed beyond recognition.

Building a buttress with eggs

In face of such great adversity, safeguarding freedom is not an easy undertaking, nor can it be achieved overnight. One must tailor actions to the objectives and retrieve our freedom bit by bit.

With regard to the system, it’s always an option for civil society to demand that a government provide structural safeguards for its citizens’ rights and freedoms as protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance by, for instance, establishing a human rights committee as a monitoring body. But given the current shape of the Hong Kong government, isn’t doing that like asking the tiger for its skin? Nevertheless, difficulty cannot be an excuse for giving up. If the Hong Kong government does not heed the demands of its people, then Hong Kongers should turn to the international community for assistance, including urging United Nations mechanisms to apply pressure on the governments of Hong Kong and China. And to make international pressure more effective requires urging China to ratify as soon as possible the ICCPR, which it has already signed.

On an individual level, everyone is a guardian of his or her own personal freedoms. The government cannot easily snatch away the freedoms to which we are entitled if we are persistent in claiming them. Foremost among them, freedom of the press should be protected. First, unlike the freedom of entry and exit or the freedom of demonstration, government officials do not have complete control over freedom of the press. Second, freedom of the press is fundamental to the protection of other human rights and freedoms. Only when news and information can be freely searched for, received, and delivered, can violations of other freedoms be exposed and remedied; even the freedoms that we do enjoy now can be further elevated through unobstructed discussions.

The biggest threats to freedom of the press right now are the government’s restriction on information flow and journalists’ self-censorship. As for the former, Hong Kong citizens should support the press in its fight for a law on freedom of information, to decelerate the government’s growing tendency toward secrecy and opacity, and safeguard citizens’ right to information. As for the latter, besides calling for journalists to firmly uphold their professional ethics by recognizing facts from fiction, citizens can also assist individuals with journalistic conscience and professionalism in establishing independent online media outlets, which can complement and function as a check and balance on the work of other journalists.

All said and done, if one wonders whether it’s feasible to be “free yet undemocratic,” the situation in Hong Kong can provide some clues. Thus, ultimately, establishing a democratic system that entails the selection of a Chief Executive by genuine universal suffrage and the formation of a Legislative Council by direct and fair election in Hong Kong is fundamental.

This, in fact, is something that the Communist Party of China understands. During its earlier struggle for power with the Kuomintang, the CPC stated in an editorial by its mouthpiece, “Freedom of the press is the signature of democracy. . . . Conversely, democratic freedom is the foundation of freedom of the press. Without political democracy, true freedom of the press is unattainable.” If the CPC upholds this ideal as a genuine aspiration rather than just means to capture people’s hearts and minds, then it should allow the citizens of Hong Kong—and the people of China—to truly enjoy democracy so that their freedoms are not eroded.

Translator's Notes:

[1] Public Opinion Programme, The University of Hong Kong.

[2] Article 23 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law states: “The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People's Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.”

The National Security (Legislative Provisions) Bill introduced by the Hong Kong legislature in 2002 to implement the article was met with strong opposition from the people of Hong Kong who feared that if put into practice, Article 23 would effectively import China’s police-state methods into the former British colony. On July 1, 2003, more than 500,000 people marched in a massive protest in Hong Kong against the bill. On September 5 that year, the Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa announced that he had withdrawn the bill, stating that the government was “not going ahead with the legislative process until there is sufficient consultation.”

[3] Officially called the Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone and located in Qianhai, Shenzhen, the new economic zone is aimed at facilitating the development of Mainland China’s financial and other service industries that will operate in accordance with international practices and rules. The target completion date is 2020.

© All Rights Reserved. For permission to reprint articles, please send requests to: [email protected].

Mak Yin-ting (麦燕庭) is a veteran journalist and former Chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association.

2019 Anti-Extradition Protests

2014 Occupy Movement

Other